A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists.

A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists.

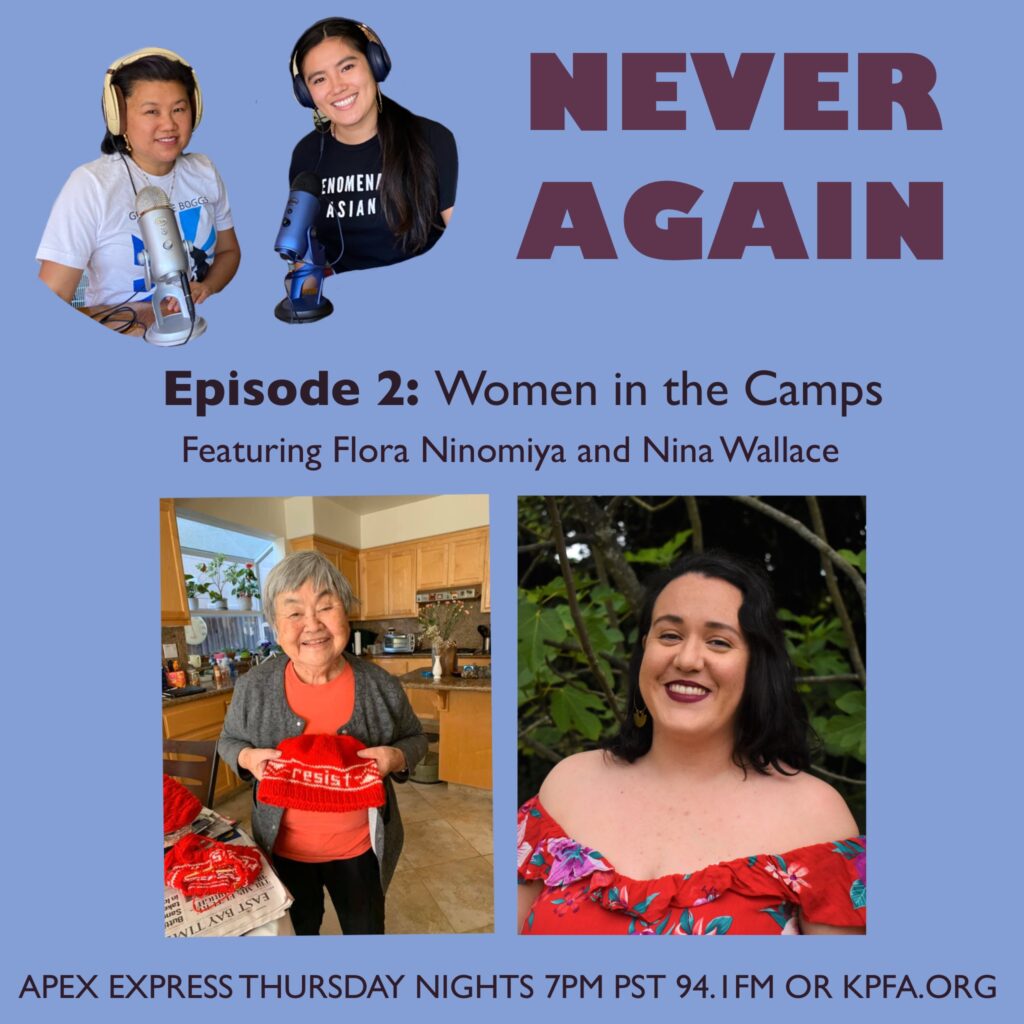

Powerleegirls Miko Lee and Jalena Keane-Lee host the #NeverAgain Series about the Japanese American internment during WW II. Episode two focuses on Women in the Camps. We hear a first hand experience from Flora Ninomiya about her time as an incarcerated 6 year old at Topaz and we talk with Densho historian Nina Wallace about women’s daily lives in the camps, as well as the dangers of sexual stalking, harassment and assault. Content warning, this show features discussions about violence against women.

This series is made possible by funding from The California Civil Liberties Public Education Program.

Show Notes:

More info on our guest, Flora Ninomiya interview in Densho

Blossom and Thorns documentary Flora featured in

More info on our guest, Nina Wallace, communications director at Densho.

Nina’s writing at Densho

Show Nina mentioned on LGBTQ+ Japanese Americans

“Seen and Unseen: Queering JA History before 1945”

Music played on this episode:

Women in the Camps Show Transcript

Opening: [00:00:00] Asian Pacific expression unity and cultural coverage, music and calendar revisions influences Asian Pacific Islander. It’s time to get on board. The Apex Express. Good evening. You’re tuned in to Apex Express.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:00:18] We’re bringing you an Asian American Pacific Islander view from the Bay and around the world. We are your hosts, Miko Lee and Jalena Keane-lee the powerleegirls, a mother daughter team,

miko: [00:00:28] welcome to our new series, Never Again, where we will explore stories about the exclusion and detention of Japanese Americans during world war II. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, president Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed executive order 9066, which unjustly called Japanese Americans a threat. Over 120,000 Japanese Americans and Latin Americans were incarcerated for over three years. The majority of the Japanese American detainees were from the West coast where they had excelled and creating robust farmlands. Pressure from the white farm industry was a major factor in pushing forth the racist internment policy.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:01:08] We will talk with surviving detainees about their experiences then and now as they continue to be active agents for change will also highlight the work of activists today many of whom carry their generational concentration camp experience into their advocacy for civil rights and civil liberties

Tonight and are never against series. We focus on women in the camps. We hear a firsthand experience from flora, Nino Mia, about her time as an incarcerated six-year-old at Topaz. And we talk with Densho historian, Nina Wallace, about women’s daily lives in the camps. As well as the dangers of sexual stalking, harassment and assault. We begin with migos conversation with flora.

Miko Lee: [00:01:48] I had the pleasure of interviewing 80 five-year-old flora, Nino Mia. Her family started a flower nursery in Richmond in 1906. The year of the San Francisco earthquake. Flora was six when her family was sent to multiple concentration camps she shares about her experience as a child in the camps

Flora: [00:02:05] my name is Flora Niyomia . I belong to the Contra Costa Japanese American citizens league, which is one of 100 chapters of Japanese Americans who are working for civil rights. And that’s who I’ve tried to represent.

miko: [00:02:25] Tell me about how you have become a civil rights activist. What made you start? What made you get engaged and excited about working for change?

Flora: [00:02:35] I’ve always been interested in civil rights for people, but after 9/11, I realized that there are other groups of people that are immigrants to the United States. We as Japanese Americans have been here much longer, but the new immigrants are having problems and they’re having the same problems that my ancestors had.

miko: [00:03:02] Tell me about where you were during WW II.

Flora: [00:03:06] Both grandparents or were immigrants from Japan and they all came in the early 19 hundreds. My father also was an immigrant my mother was a Nisei, which means that she’s a second generation and she was born here in California. So I’m not really a Nisei. I’m not really a Sansei. I’m a two and a half say because my father,

miko: [00:03:36] so did you grow up in Richmond?

Flora: [00:03:38] I was born in Richmond. Everybody in our family was born in Richmond, except my youngest sister who was born in a mochi when we were all incarcerated. We’re all native Richmonders. We’ve all gone to Richmond schools. And we’ve all been to college because we were able to do that because of my parents . I’m proud to say that I’m a graduate of Richmond high school. And then I went on to college.

miko: [00:04:10] How old were you when you heard about when world war II,

Flora: [00:04:15] when world war II started? I was six and a half years old. And we had to leave Richmond early

miko: [00:04:22] do you remember that? Cause you were pretty young.

Flora: [00:04:24] I do remember the chaos that we had because it was a very difficult time. The day that we left Richmond was the day that we were going to go to live in Livingston, California, which is a farming community. That was the very day that my father was arrested by the FBI. So he did not join us when we moved to Livingston. My mother was there with us. There were five children and my paternal grandfather was also with us.

miko: [00:04:57] What were your emotions at that time?

Flora: [00:05:00] Our parents tried to protect us as much as they could. I didn’t feel worried or anything, but it was a shock that my father was not with this because he was, taken away. I know that he was being watched by the FBI from probably December until the day in February, that we left Richmond.

miko: [00:05:25] Where was he taken to?

Flora: [00:05:27] Where he ended up was Bismarck, North Dakota. We just had no clue where he was going or what he was doing. We, children were picked up by our relatives and we left Richmond and my mother came later. She was very distressed that, he was picked up by the FBI, but, she was pretty tough. She made the best of it. She had to take care of us. She had to also take care of my grandfather. So she just did what she had to do. My mother was quite well, both my parents were remarkable.

miko: [00:06:06] Where were you sent to from there?

Flora: [00:06:08] We went to the Stockton assembly center. Then we found out that the people from Stockton we’re going to be sent to Arkansas. My brother had a very bad asthmatic condition. So it was decided that it would be better if we went back to, from the Stockton assembly center to the Mercedes assembly center and go into camp in a more desert, like area. I remember the train ride through the desert. It was just really a very unpleasant experience because it was so hot. I wasn’t accustomed to that kind of weather and the train seemed to be going on forever and ever. I remember the train ride much better than any other part of, that whole experience.

miko: [00:07:06] Was it all Japanese Americans on the train.

Flora: [00:07:08] They were all Japanese. They moved everybody as a family. Everybody was on the train together and it was a real, awful train. It was very uncomfortable, not clean. It was really bad.

miko: [00:07:22] So were there people that you knew on the train outside of your family?

Flora: [00:07:25] Yes. The people that were on the train were all from the Livingston area. My mother had lived in Livingston. They were her friends, her farming friends.

miko: [00:07:36] Do you remember the first time you got off the train.

Flora: [00:07:39] I don’t remember getting off the train. I don’t know how we got to our barracks, It was, all so so chaotic, so unorganized and as a child, you just do, as you’re told. Tried to follow what my mother wanted me to do. Livingston is a farming community. Most of the farmers in that area are from the rural parts of Japan . I did not realize this until I became an adult, 50% roughly of the Japanese in the United States were farmers, but of that 50%, I realized that there were two kinds of farm families. There were those families that own property or had farms and there were the other 50% were farmers, but they worked for other Japanese families. Those families didn’t have a permanent position . And my mother’s family did not own a farm. In Livingston, we were in a farmhouse . It was temporary , because we knew that we would have to go into a concentration camp. It was a very old dilapidated house and it had no indoor plumbing. The kitchen was very primitive. It had a hand pump and you had to pump the water and this is already, 1942, it had no electricity. It was really a shack.

miko: [00:09:19] What was the first concentration camp you were sent to?

Flora: [00:09:22] So the first concentration camp was a temporary camp and it was in Stockton because we went to Livingston and then we moved to Stockton so that we could go into camp with my uncle. And then we went into the Stockton camp and then from there we were transported to Merced. And then from Merced, concentration camp. We took the train to Colorado.

miko: [00:09:52] Oh, you went to a lot of them.

Flora: [00:09:54] Yeah. Was in the first grade, I think I moved six times . School that was a blur. It was difficult when we finally started regular school in Colorado, I was behind. When we were in Colorado, the school was very well-organized and I think there were at least three or four classes in every grade level. It was the first time in my life that I had so many Japanese American friends because in Richmond there were only 20 Richmond and El Cerrito. There were only 20 Japanese American families that were, in the nursery business were farmers. It was really quite a revelation to see all these kids that were Japanese Americans. About half of the people in Colorado were from Los Angeles. They were city kids and, we were country kids.

miko: [00:11:01] What do you remember most about that experience in Colorado?

Flora: [00:11:05] I think that it was a wonderful time for we children because we had no worries. We had lots of friends and all we had to do was do well in school. It was, very enjoyable. I can say that as a child.

miko: [00:11:23] Do you think there were things that you learned about Japanese American culture there that you didn’t learn when you’re in Richmond?

Flora: [00:11:30] One thing I didn’t learn was. We did not have Japanese schools. And so I still, can’t can read or write in Japanese and here I am, I’m going to be 85 years old this year. I can still speak Japanese enough that I can communicate, but I love to watch NHK, which is in English here, of course. When I go to Japan, I can’t really understand watching the news and Japanese because they talk too fast. I do speak enough Japanese that I can speak to a taxi cab driver and, we can converse but I can’t speak a very complicated Japanese. .

miko: [00:12:21] So when you got out of the camps, you came back to Richmond.

Flora: [00:12:24] Yes. We were very fortunate because practically every nursery family in Richmond, there were 20 families and we all were able to return to our nurseries. Only one family did not return. And I speak about this because there are two people that were really People of conscience that made it possible for our family to come back. First was our neighbor, Mr. Francis, Aebi Sr., who lived right across the street from us. He took care of our nursery and was able to make enough income on our property that he could pay our property taxes to Contra Costa County.

But also there was a second man. His name was Edward Downer Jr. And he owned the mechanics bank and he had a mortgage on our property and he did not call the mortgage. He did not receive any income from our family all during that time. He just quietly held our mortgage all during that time. So it’s because of these two people, for instance, Aebi Sr and Edward Downey, Jr. That our family was able to come back. One family that didn’t come back, had their mortgage at a different bank. So I think that Edward Downey Jr was truly a man of conscience, just like Mr. Aebi.

miko: [00:14:08] So when you came back, how old were you?

Flora: [00:14:11] When I came back, I was 10 years old. I entered the fifth grade at the same school and we were truly welcomed. We were welcomed by the teachers. We were welcomed by the students and the principal of the school was my kindergarten teacher. And we had a connection and all the teachers just really were wonderful to us.

miko: [00:14:39] Did anybody talk about where you had been or what had happened?

Flora: [00:14:43] You know what? I never talked about it. I never talked about being in camp people did not ask me when we were that young. Yeah, no one else.

miko: [00:14:53] So when did you start talking about it?

Flora: [00:14:56] When I started speaking at Rosie the Riveter, I kept my mouth shut for all those years. I was embarrassed to talk about it because I felt that somehow we had not, we had done something wrong because. Why would it be treated that way if we had been okay. If we hadn’t done anything wrong. So I just didn’t talk about it.

miko: [00:15:24] What was the catalyst that made you start talking?

Flora: [00:15:27] I thought it’s important that people know about it. I was in my seventies when I first started speaking and now I can’t keep my mouth shut

miko: [00:15:38] Was there a thing that happened that made you that pushed you to open up about this?

Flora: [00:15:44] When you were speaking in public and trying to tell of your experience, you could talk honestly, and talk about this experience, even though you did not want to speak about it before. It gives you lots of freedom to speak in front of audience and speak that way. Speak your mind.

miko: [00:16:06] So fast forward 9/11 happened and you decided “I have to get out there and say something.” What was your first action? How did you do that?

Flora: [00:16:17] I didn’t start speaking immediately because there wasn’t this opportunity to speak. I’m a person of faith. So I do go to church and we did, think about, how we could help the Muslims, but I did not speak. It’s only when I connected everything and realized how. The immigrants have come to the United States and this unfairness happens over and over again to each new group that comes to the United States seeking a better living. When you start connecting what the experience of the first immigrants was. Then you see it happening to every new group that comes the Vietnamese, the Muslims, the Filipinos, any of the Southeast Asians, the people that come from Africa to seek a better life here in the United States, it happens over and over again. So in order to make people aware of what has happened to us, we couldn’t relate that to the new experiences that the new immigrants are having.

miko: [00:17:46] Have you been back on pilgrimages to any of the sites that you are held?

Flora: [00:17:52] I have been to Topaz. There was a opportunity to go on the bus and we spent Six days together on the bus going to a Topaz and it was wonderful.

miko: [00:18:07] What was that like for you to be with other former internees and returned back?

Flora: [00:18:13] Group that went were all ages. Some people were older than I am. And of course there were sansei’s that were hearing about these experiences and asking questions. So it was a wonderful time for all of us. They have a wonderful museum at Topaz.

miko: [00:18:35] How was Topaz different from the one you stayed at in Colorado?

Flora: [00:18:38] Topaz is very similar in the fact that it’s very desolate to desert area. their museum is very well-developed. Whereas in Granada, they’re just getting a program started by doing a lot of excavations. I’ve not been back there, but I have, friends that have gone . I still haven’t been to Manzanar, so I would like to go to Manzanar.

miko: [00:19:06] Why do you think it’s important for people to visit the internment centers?

Flora: [00:19:11] At most in Japanese, American museums they have depictions of what the camp living conditions look like. Think that’s a good thing. At the San Jose museum, they have a room that looks like the conditions that we had. At Manzanar, I know that they have rooms that look like the rooms that we have. It was very primitive, no running water. Electricity at the bare minimum. The heating was very simple. Think that people should see what it was like within the camps and how everybody was crowded into one large room. it was really difficult for families. In our family, there were five children, my mother and grandfather, and we’re all in one room. It was very difficult. It was hard.

miko: [00:20:14] What do you want young people now that are growing up in, let’s say Richmond, let’s say the same schools you went to. What do you want them to understand about what you experienced?

Flora: [00:20:26] I do go to speak at Richmond high school to their history class every year. I do talk about my experience and people have to understand that we, as American citizens were placed in the prison camps and we were put behind barb wires and we were in living conditions that were, I thought very difficult for families to live in. We were not just behind barbed wire, but also the army was patrolling us and they were in the watchtowers and they had weapons that could too, that could kill you. So it did happen that Japanese were killed within the camps by the American army. The students that we speak to should know that this happened. It’s not right

miko: [00:21:34] earlier, you were saying that you never talked about it for many years because you somehow thought this was my fault. How do you feel about that now?

Flora: [00:21:42] I should have spoken up and I should have explained to people what happened to the Japanese and Japanese Americans. I don’t feel good about that, but it’s never too late. I’ve tried to do my best, so I try to speak whenever I’m asked and I try to share our experience and I always ask for questions. And that’s how I’m trying to make up for not speaking up earlier.

miko: [00:22:15] What’s a question when you go out and speak in all these different places, what’s a question you wish people asked you.

Flora: [00:22:22] I think that I shouldn’t wish for any questions. I tried to give information to people and I don’t wish that people ask me things because if they don’t ask me a question, they really aren’t interested. They don’t want to know. So I don’t try to. Think of what people should be asking. It’s what they should be asking is not my business to be saying. So I don’t think that is important.

miko: [00:22:57] So right now we’re seeing on the borders of our country, all these children that are putting cages. Tell me what your thoughts are on that. And how do you equate that with your experience?

Flora: [00:23:09] We weren’t put in cages. We weren’t separated from my mother. She was always there with us. I think it’s deplorable. That’s not the way we treat our fellow human beings. I don’t think that the children should be separated from their parents. I don’t think that they should be kept in cages. I just. Do you poor the action of our government? It’s not right.

miko: [00:23:44] Can you talk about the significance of Tsuru for solidarity? What is a crane symbolize? What does it mean to hang those on the fence?

Flora: [00:23:55] I think that tsuru are symbolic of a long life. They’re symbolic of one of the first things that you learned to fold as a child and It’s just a very symbolic thing for Japanese Americans, so that I think and having One crane for each person that was incarcerated. I think that and many of those people are no longer living because this happened in 1942 to 1944, 45. It’s very symbolic that we do this for, especially those who are no longer here. We’re doing this to show that we are still fighting the inequality in the United States. We’re fighting for freedom. We’re fighting for peace at the same time. That’s something that is very important to me.

Miko Lee: [00:25:04] Flora had paper cranes all around her house in Richmond, along with pamphlets for the day of remembrance and piles of yard for resistance hats that she was knitting. She has made many, many hats and it’s pictured on our website wearing one of her cute resist hats.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:25:19] Next up, we hear ADI Gato. By Okinawan rapper.

She’s the only female member of japan’s famed yen town collective

That was ADI Gato. Next step, I spoke with Nina Wallace, who is the communications coordinator at Densho a Seattle based nonprofit dedicated to sharing stories of Japanese American incarceration during world war II. Nina is Yonsei. A fourth generation japanese american who believes in the change making power of personal story and community history. Content warning for our listeners that this interview with nina we’ll be discussing interpersonal violence against

Thank you so much for joining us. Can you tell us a little bit about your personal story in connection with the internment camps?

Nina: [00:27:48] Sure. So yeah, so my name is Nina Wallace. I’m the communications coordinator at Densho, which is a Japanese American kind of history and education org based in Seattle. And I am a yonsei, so fourth generation, Japanese American. My family actually wasn’t in camp. During the war by a very lucky set of circumstances where they just happen to be outside of the quote unquote exclusion zone, where the government decided that Japanese Americans living there had to go into the camps. And they narrowly avoided going to camp. Because the, so the government was planning to make the area where they lived part of this exclusion zone. But the people who lived in this town where they were at, spoke up for them and said, Hey, like we know this family you shouldn’t do this to them. And so they were very lucky compared to a lot of families.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:28:48] And how did you get involved in. Advocacy around internment and specifically for women that were in the camp.

Nina: [00:28:56] Yeah, so I’ve worked at Densho. I’ve worked at Densho for about 10 years now. I started as an intern pretty much out of college. Just transcribing oral histories, interviews with elders who were in the camp. I actually owe that to my mother, cause she was the one who just told me about the Job opening. And the timing just worked out that as my internship was ending, they had a position opening up on staff. A big part of what I really enjoy about this work is uncovering some of these like hidden histories and these like lesser known topics that we don’t hear as much about when we talk about, Japanese American history or incarceration history.

I started in the wake of, when the me too movement was really prominent, we realized that, this was a big hole in our archives and that we didn’t have really any stories or documentation of, the experience of survivors and the camps and, and not a lot just generally on women’s experiences with incarceration. Recognizing that these were stories that were not being told. I feel like I don’t always see myself in the historical record.

As an Asian woman, as a queer woman, as a mixed race person, I’m like, I don’t see myself. Documented in history as often. And so in part of my motivation and looking for these stories is just wanting to maybe a little selfishly or self indulgently wanting to see myself and know that, you’re not alone in your experiences. like a lot of women, I have my own, me too stories. I think specifically, researching sexual violence during world war II incarceration I think on some level it does feel reassuring or empowering in a way to find those stories and know that, other people have experienced that too. I really want survivors and, women and queer folks to be able to see these bigger systems and these bigger pieces of history that create this violence. And to know, this is created by something bigger than you and you’re not alone. And navigating this.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:31:27] Thank you so much for the work that you do. A lot of us really appreciate it and feel the same way about, not being seen in these history books and in these even, more radical texts about history and movement leaders. So we’re really grateful for that. I’m curious because it seems like there’s, two different kinds of violence. There’s like the interpersonal, sexual violence, and then there’s another layer of violence of being erased. I was wondering if you could speak to how that operates the ranger, both. Vertically, like from the top down from, people that have power in our society and those decision-makers that do get to write history books, do that kind of more mainstream media, but then also within our own communities, there’s this predominant silence around things that are considered shameful and painful.

Nina: [00:32:12] Yeah. When I started doing this, like something that I guess I shouldn’t say it like, it, it didn’t surprise me. It was still disappointing is that, there’s so much literature and, films and memoirs and, and just there’s so much documentation of This history of, Japanese American incarceration. But when I started doing this, I realized that there was like nothing on sexual violence. And there was like so little that actually centers women’s stories in that experience.

When we talk about this history, we tend to talk about these big picture things. We talk about economic laws and we talk about, the breakdown of traditional families, which I think is a code word for breaking down patriarchal family structure. The historical record is incomplete in that way.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:33:10] It’s like both, what is the, the factors that are raising these stories that are external to our community and then the ones that are internal within our as well.

Nina: [00:33:21] I think external eraser where, we’re talking about kind of mainstream history and the way that they like. Primarily white institutions decide what is, and isn’t worthy of recording. Or which stories are worthy of being told, like very often those institutions decide that stories about people of color about immigrant communities are not worth telling. I think, already there are some barriers just to telling Japanese American and Asian American history And even though there has been a lot written and said about that history it’s still in a lot of spaces isn’t really treated with the same weight as like the founding fathers or, some of these other Histories that are more prominent in like textbooks and classrooms and all of that.

So there’s already some erasure, like you said, coming from the top down. But then I think when we’re getting specifically into like women’s history or some of these other histories of people who are more marginalized within already marginalized communities there’s also pressure from, our own communities to not talk about things that you maybe are seen as shameful. So things like sexual violence queer sexualities sex work he’s things that They are often shamed within our own community.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:35:10] Thank you so much for sharing that. I’m curious too, about your self care practice and what you do to process these things. Stories that it’s research in your own body and for yourself as you do this work?

Nina: [00:35:23] I love this question. To be honest, I feel like it’s, it’s a process that it’s something that I think, it’s a process to remember that. Yeah, you do have to do that work. Cause I think it, it does take a toll psychologically physically, emotionally all of the above. You’re immersing yourself in like in this case it’s like a lot of just reading through, case files of, just the worst moment in someone’s life., if you you relate to some of what you’re reading or you recognize or share some of those experiences. It can be a little triggering and it can be it can be difficult. Part of it is, just knowing when to take a break or just like forcing myself to take a break sometimes. Just being, giving yourself some time to breathe and to go outside, take a walk and breathe, fresh air and be in nature. I think part of what sort of drew me to these stories and this research is, again like looking for a sense of community in a way . Like shared experience and I think you get you’re looking within the historical record for this, but no, but the community still exists today.

There are still people who are doing survivor work today and are doing amazing things to break some of these silences and support each other and lift people up. Finding that community in the present moment and reaching out to people who are doing amazing survivor work and other people that are having these conversations, that don’t treat it as this sort of shameful, dirty secret and also lots of baking.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:37:18] Yes. I love baking too. I’m curious with all the recent uncovering, I guess would be the right word of just the levels of violence that are happening in migrant detention centers today. What kind of stuff has that brought up for you and connections to your work? I know it’s a really important for, everyone who was involved in Japanese interment to, to be really vocal about “Never Again, let’s not let this happen again.” And yet we do see it happening right now. So what are the lessons that we can learn from this time and in WW II times?

Nina: [00:37:53] Yeah. Yeah, it was pretty devastating to hear about the forced hysterectomies that are happening in the migrant detention centers. Now, I think it’s another one of those things that, it is shocking and terrible when you hear about it, but it also when you think about even just like the current contemporary context of what we know is happening and what’s taking place. And then also within this bigger historical context of how this country has always treated. Women of color and immigrant communities that, it unfortunately is not that surprising. It is par for the course in a lot of ways, which is itself a really devastating fact that this is something that you know, is banal, so we take it for granted that, Oh yeah, this is just life in America. Our government is carrying out forced sterilizations of women of color. Yeah. When we’re talking about, the historical connection there, wasn’t a, this kind of systemic like mass sterilization of Japanese American women in the camps. You do hear stories about, women who went in to the camp hospital to get their appendix removed or to like to give birth and then found out years later that the doctor also decided at that moment to perform a tubal ligation on that there’s Is a testimony that a woman gave during the redress hearings in the 1980s, where she talks about her mother, when she gave birth to her, in Tule Lake the doctor performed a tubal ligation on her and, she didn’t find out until years later that this had happened.

She didn’t give consent to it. It was not something that she wanted. So you hear those stories here and there. I know that there also was a Senate bill that was proposed in 1945. It didn’t pass, it, didn’t go through, but. There were us senators discussing forcibly sterilizing, Japanese American women on the Senate floor in 1945. You get a sense of kind of what the atmosphere was like and what what kind of views people had about Japanese American women. I think that you see a lot of that same sentiment today. And I also think it’s important to say also that this wasn’t something that just came up in Japanese American history. This was also a huge thing for black and indigenous women who were forcibly sterilized for decades. And up until very recent, certainly. And and I think all of these, you can trace these sort of historical threads to different places that we’re at today. You see it in the migrant detention camps, you also see it in, the way that the infant mortality rates for black communities and, maternal mortality rates for black women are very high today. So I don’t think that you can really separate out these different threads, all part of the same picture and the same system that just devalues women of color and weaponizes reproductive healthcare to, carry out this white supremacist agenda that this country was built on.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:41:34] we know that, going to the doctor was a really dangerous or could potentially be really dangerous for women in the camps, then and now, but in the Japanese internment camps, what were the other places that were seen as like high-risk or the most dangerous for women specifically?

Nina: [00:41:50] Yeah. Yeah the latrines were a big site of violence in the camps. People talk about it and the women talk about it, even for women who may not have experienced sexual violence themselves, there’s still as this kind of fear looming over it. I’ve just knowing that there is a not unlikely chance that, something as simple as, as going to the bathroom Could result in an assault or some form of violence. There are historical records and it’s recorded in a very nonchalant way. A lot of times too, it was just like, Oh yeah, there are men like peeking in on the women, in the showers or there’s a couple of stories about older men going into the women’s latrine and like propositioning, teen girls for sex and offer them money for sex or people following women home from the latrines.

It’s hard sometimes to conceptualize a little bit, I think as a reminder, like these the latrines, like the places where people were accessing showers and toilets were actually pretty far their barracks, like where they lived and where they no slept and had all their belongings. And if you had to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night that could be a pretty scary thing to have to, walk maybe like 10 minutes to get to this bathroom. And there may not be anyone else around. So a lot of people, not just women, but just, people in general who may be. No. Didn’t like the inconvenience of that or your elders who maybe couldn’t make that walk comfortably. A lot of people just started using chamber pots at night where they would just be able to avoid going to the bathrooms and the men that are, In the euphemistic way, like creeping in on them.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:43:58] Are those other internees or are those guards, and was the violence coming both from, other Japanese people that were in turned and the guards or mostly just from other internees?

Nina: [00:44:07] Yeah. It was definitely a combination of those things. I think that. It’s hard, right? When we’re talking about sexual violence that occurred, like 70, 80 years ago, there is a lot that just was never recorded and that we’re never going to know about. And there’s always a degree of feeling in.

Some of the gaps are like reading between the lines, just based on, maybe like your own lived experience or like things that we know today. Most of what is in the record is know that kind of interpersonal violence, where it is Japanese American men who are assaulting or abusing Japanese American women and girls.

There are, some documented cases where it, it’s a guard or an employee in the camp who isn’t acting violence. But you don’t hear those stories as much and, and part of that I think is probably just, like abuse happens when there is access. And when they’re when it’s easier for abusers to do that but I think, there’s also power dynamics, right? Between, like camp guards or camp administrators, and then the inmates in the camp. Like you can make an assumption that isn’t, is it very outlandish to assume that, maybe there are more cases that weren’t recorded because of who is controlling the record? So again, the short answer is, most of what I’ve come across has been lateral violence where it is Japanese Americans who are harming other Japanese Americans. But there are cases where it’s, guards or administrators who are doing that as well.

And speaking of, who gets to tell the story in the case of, how these stories are recorded and the fact that so many of them are lost because people like you were not there closer to what had happened to get the female side of things, the queer side of things and all these different facets of the stories that have been left out, up until now.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:46:24] I’m curious your thoughts about general our society, like suppressing women’s roles in social movements and how the United States views world war II in general, in terms of storytelling, like there are so many movies about world war two with the United States positioned more as more compassionate to more like helping people and not exactly like a benevolent imperialist, but not very much about Japanese internment or, all the other things that happened in that same time. So I’m curious if you have any thoughts about that and that position of being a storyteller or a historian and a record keeper.

Nina: [00:47:04] I think, you hear this phrase a lot or, but the idea that there is no such thing as an objective historian or an objective journalist, or, just, an objective, anything, right? We all have our own experiences and biases and perspectives that shape how we look at the world and so that is true for historians and for people who are recording history as it unfolds. I think that is very much reflected in kind of what we have today and what we’re able to see of the past today. Part of your question around, just like women’s roles in social movements. I think that, there’s definitely a devaluation of, feminized labor. Maybe it’s I don’t know if that’s the right word to call it, but I think that women a lot of time in movement spaces and organizing spaces. Yeah, I don’t even think this is something that’s just true historically. Like this is something that, I think we still very much see in organizing spaces today where a lot of times we see women and, fems and non-binary people taking on more of this like invisible labor of like historically maybe that’s making copies and, taking notes from meetings and posting up flyers and things that are not as sexy as getting up and speaking in front of a rally and, riling people up and being the face of a movement, but things that, really carry them on their back, because like, how do you have a movement without. Getting your message out without recruiting people to come and join and being able to catch up and the minutes are like the notes from what happened at the last meeting.

So I think a lot of times we see women and again, like other kind of marginalized people taking on more of that invisible labor. Whereas, we see a lot more men and and especially like SIS. Hetero men becoming the face of the movement. And yeah, just like in that way, I think women have always been very instrumental to social movements, but don’t always get credit for that just because of the kind of labor and contributions to those movements.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:49:49] I’m curious if there’s any stories about queer people in the camps or any documentation about queerness in the internment camps that you’ve come across.

Nina: [00:49:59] There is very little sadly about queer folks in the camps. But there is some. Like if you go looking for it, you can find it. Right now there is a virtual exhibit on queer Japanese Americans during and before world war II. It’s the first exhibit that there’s ever been that’s specifically about LGBTQ, Japanese Americans . So I would recommend that people check that out. There’s stories of queer folks, like in a historical record, a lot of times, like what is there is just records of criminalization. So you don’t really find stories of, like queer love. The stories of people like thriving as much as you do people, being criminalized and harmed Which is, it’s sad and I, I hope that we’re able to find more stories of love and thriving.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:51:03] I just have one last question, which is what is keeping you hopeful in these days?

Nina: [00:51:09] Something that gives me hope is, especially in the last few years, there is a renewed interest in finding these untold stories and recognizing that the way we have talked about history and recorded history for a long time erases a lot of members of our communities . It was very intentionally trying to center and amplify stories that haven’t been told before. I think that is really empowering and inspiring. Also seeing people not just like historians or journalists interacting with this history , but also artists and poets and a lot of young people coming to this history and kind of interpreting it in their own way and activating that history in their own way, I think is really inspiring.

I also think you mentioned this earlier about how, especially for, Japanese Americans who experienced the incarceration during world war two, a lot of them are saying never again is now, right? Seeing immigrant communities targeted for detention and deportation, seeing this kind of repetition of that history, which in, in itself can be very depressing, and very hard to watch. But seeing the way that a lot of our elders are really leading this fight to prevent that from happening or to just stop it. Groups like for solidarity organizing with undocumented communities to stop detention deportations, I think seeing that kind of multi-generational activism is very encouraging and very helpful.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:53:15] Next up, listen to its first light. I just given name is So You’re a saki check out her latest eap partition which is all about questioning the confines placed on women

You just lifted to ICAS first light.

Miko Lee: [00:55:21] So, what were your biggest takeaways from the show tonight? I was thinking about how so many different ages of people were impacted. And flora was incarcerated from six to 10, which are such formative years for a young person. And as a young person being around so many other Japanese Americans for the first time in her life, what an experience that was like for her.

And what does it say about our society that she grew up in Richmond and she wasn’t able to have an experience of being around so many other Japanese Americans. That must’ve been hard.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:55:54] It must’ve been really hard and. I mean, it’s such a privilege to get to talk with her. And that there’s people that experienced interpret that are still living, that we can, you know, get these firsthand accounts from. But also it must’ve been really hard for her mom and her family to create that kind of environment where she could feel that.

And I’m sure that that was a big emotional toll that was placed on women to kind of uphold the family dynamic and the family spirit and morale through these really hard times. And I really appreciated talking with Nina as well about. These, , untold dynamics and sides of Japanese internment, like knowing thrill of trains are so far away and how much went into, planning to go to the bathroom and who you were with and the ways that.

It was written about is kind of like people were being peeked in on, and all the lateral violence that people faced while in the camps . And so many hidden stories of what women had to just deal with every day, how they had to struggle and go through their lives. And we just don’t read that much or hear that much about the camp experience from a women’s perspective.

So luckily there are still women alive today, like flora who can give us that perspective. And there are also women like Nina that are doing the work to make sure that that archive is available for future generations.

Thank you to all of our guests on this episode, please check our website, kpfa.org/program/apex express for links to find out more about each of our guests tonight. We’re in the process of developing a study guide and online teacher training so stay tuned we thank the California Civil Liberties program for making this series possible.

Thank you for listening we’ll see you next time on apex express

Miko Lee: [00:57:33] keep resisting, keep organizing, keep creating and sharing your visions with the world. Your voices are important. Apex express is produced by pretyt Mangala. Checar Tracy. When Mico Lee Angelina keenly tonight show was produced by your hosts, Mico Lee, Angelina keenly. Thanks to KPFA staff for their support and have a great.