A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists.

A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists.

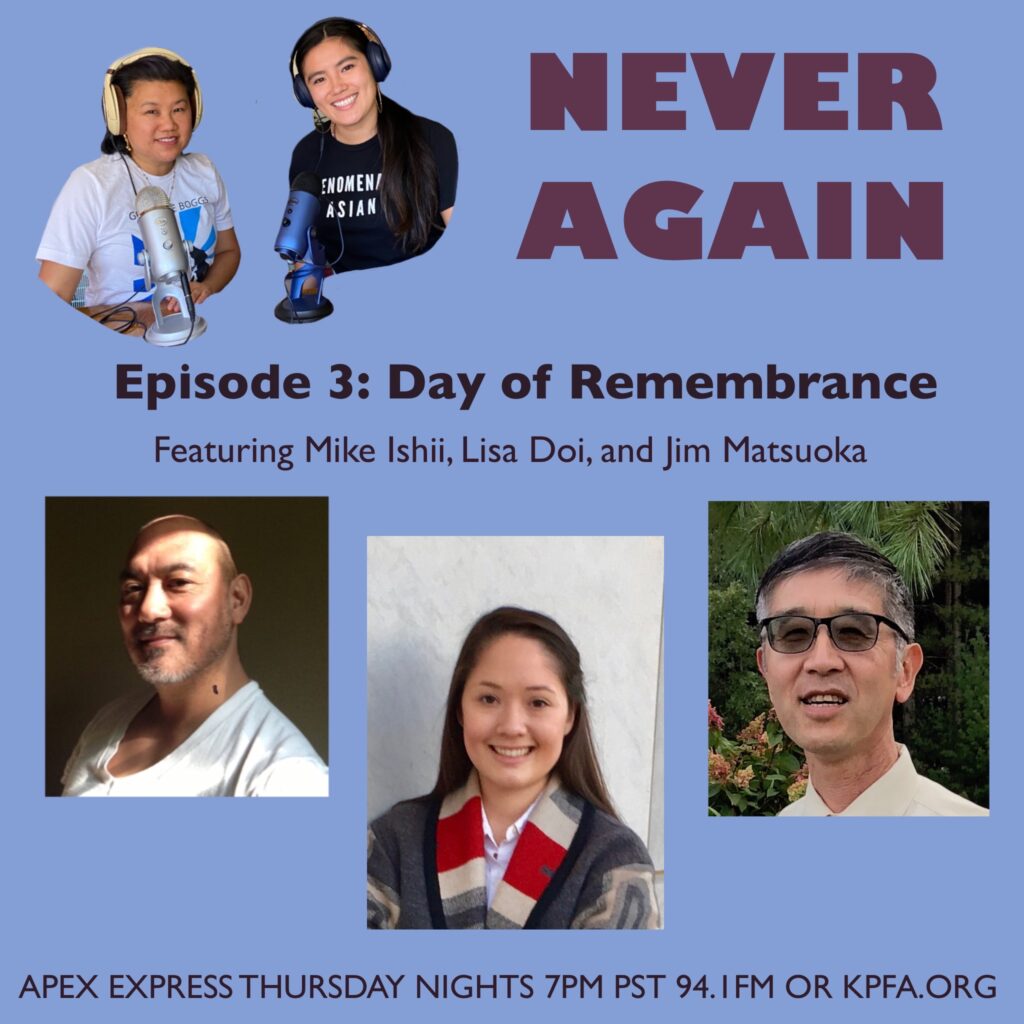

Powerleegirls Miko Lee and Jalena Keane-Lee host the #NeverAgain Series about the Japanese American internment during WW II. Episode three focuses on Day of Remembrance. We hear from Tsuru for Solidarity Co-Chair Mike Ishii about events happening in New York. Lisa Doi, Director of the Japanese American Citizen’s League updates us with what is going on in Chicago. Chair Jim Matsuoka tells us about Bay Area Day of Remembrance events.

Content warning, this show features emotional memories about the incarceration of Japanese Americans and Japanese Latin Americans.

This series is made possible by funding from The California Civil Liberties Public Education Program.

Upcoming Events discussed in show

Love Our People, Heal Our Community –united to condemn harm against our elders, women, youth

February 13 3-5pm PST, Madison Park, Oakland Chinatown (in person – utilize covid19 safety protocols)

Day of Remembrance events

February 14 3pm PST online

San Jose: Confronting Race in America: Unifying Our Communities

February 19 6-7:30pm PST online

Bay Area: Abolition Reparations! Carrying the Light for Justice

February 19 7 AM PST (in person – utilize covid19 safety protocols)

New York: Day of Action to End Immigrant Detention

February 20th 11:30 AM PST online

New York: Virtual Day of Remembrance Program including speakers, candle lighting, and a community raffle.

February 21 12pm PST online

Chicago: Righting Historical Wrongs: Connecting Black Reparations and Japanese American Redress

Chicago Facebook event here.

Other Day of Remembrance activities online

Transcript from Day of Remembrance

Day of Remembrance Show

Opening: [00:00:00] Asian Pacific expression unity and cultural coverage, music and calendar revisions influences Asian Pacific Islander. It’s time to get on board the Apex Express. Good evening. You’re tuned in to Apex Express.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:00:18] We’re bringing you an Asian American Pacific Islander view from the Bay and around the world. We are your hosts, Miko Lee and Jalena Keane-lee the powerlee girls, a mother daughter team,

miko: [00:00:28] Welcome to our new series, Never Again, where we will explore stories about the exclusion and detention of Japanese Americans during world war II. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, president Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed executive order 9066, which unjustly called Japanese Americans a threat. Over 120,000 Japanese Americans and Latin Americans were incarcerated for over three years. The majority of the Japanese American detainees were from the West coast where they had excelled and creating robust farmlands. Pressure from the white farm industry was a major factor in pushing forth the racist internment policy.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:01:08] We will talk with surviving detainees about their experiences then and now as they continue to be active agents for change will also highlight the work of activists today many of whom carry their generational concentration camp experience into their advocacy for civil rights and civil liberties

Tonight in our Never Again series we focused on the Day of Remembrance. We begin with Miko’s conversation with Mike Ishii Tsuru for solidarity and Day of Remembrance co-chair in New York.

Miko Lee: [00:01:38] Welcome Mike Ishii to apex express.

Mike Ishii: [00:01:42] It’s such a honor to be here in conversation with you. I’m Mike and I’m one of the co-founders and co-chairs of Tsuru for Solidarity. I am based out of New York city.

Miko Lee: [00:01:53] Can you share with us your personal connection with the internment?

Mike Ishii: [00:01:59] Was born in the mid sixties and I was raised in a family where my mother’s entire family, including her were incarcerated at the war relocation authority camp called Minitonka and that was located in Idaho during world war II. I’m the descendant of a survivor and every single person on my mother’s family was incarcerated. My father’s family was not incarcerated. They were also Japanese Americans, but there was a very short period where people were allowed to voluntarily leave the West coast in order to avoid the forced removal. His family had distant relatives in Worland, Wyoming. So they fled to Wyoming where he actually lived a life of poverty. They lived in a chicken coop for one period of time and avoided incarceration, but nonetheless indured, quite a bit of hardship.

Miko Lee: [00:02:58] Do you remember when you first heard about the internment?

Mike Ishii: [00:03:01] I have this very, the distinct memory of being a young boy in grade school and my mother asking my siblings and I, if we wanted to accompany her to the Puyallup fairgrounds in the Seattle area. That was for the very first Day of Remembrance ceremony that was organized by Frank Abe , who is a beloved organizer, filmmaker and activist from Seattle . His close friend was my father’s brother, David, who was just eccentric activist and independent bookseller. Create a salon for Asian American writers and my uncle David was involved in that first day of remembrance.

My mother brought that up to us as children and she wanted us to accompany her. And to my regret to this day, I remember saying to her ,”I don’t want to do that.” As a young boy, I didn’t really understand what the event was. So I missed it. As a community organizer now, especially around issues of post-World war two incarceration, healing, the effects, the intergenerational effects of the incarceration, and certainly as an activist to close detention sites, I really think back on that story, it’s formative, but I wish I had made a different decision in that moment.

Miko Lee: [00:04:26] What would Mike today say to little Mike to get him to go then?

Mike Ishii: [00:04:32] That’s a great question. I think maybe little Mike would say to big Mike “Mom would be proud of you.”

Miko Lee: [00:04:39] So that was your first Day of Remembrance. Can you talk with us about what day of remembrance signifies and why is it important?

Mike Ishii: [00:04:47] It has a lot of emotional resonance for me. One of the very first people I met when I came to New York city as a young student, at the Julliard school and the first person I called in New York city, because I had been given her phone number was Yuri Kochiyama.

Yuri invited me to be connected to the day of remembrance committee. In 1989, Julliard was undergoing its own moment of accountability around institutionalized racism. I was very involved in that community conversation and it was a challenging one.

As a result of those conversations in the school, students of color organized the first Martin Luther King day celebration, and I created a performance piece, including dancers singers musicians and actors. We did a piece that was based on this story of my family in Minitonka and Yuri and Kazu Ijima came to that performance.

Then they asked us to perform it at the New York, Day of Remembrance event a few weeks later. That was how I first got connected to the day remembrance in New York city. And I’ve been connected ever since. I’ve been one of the co-chairs for over two decades now, it’s been a very central part of my adult life. That work really shaped me as an organizer and an activist and my relationship with Yuri and you way Glynn Julia Zuma, Leslie, another Wong Sasha Hori and Sasha’s daughter, who is one of my most treasured friends and one of the other long-time co-chairs of the. So it’s really been a central part of my life as a new Yorker and certainly as a conduit to my connection and growth as a member of the Japanese American community nationally.

Miko Lee: [00:06:51] Talk to me about this year’s day of remembrance . How are y’all adapting and what is this year’s 2021 day of remembrance about.

Mike Ishii: [00:07:02] New York, Day of Remembrance works very closely with Tsuru for Solidarity. The organizing members of NYD are also working in the Tsuru leadership and community communications committee as well as in the co-chair committee. So we work very closely together and really following the vision and the leadership of yuri and Meechie and Yuri’s husband Bill and many others.

It’s been important for us to really follow an understanding that the abolitionist movement has always embraced and that’s to align ourselves with directly impacted communities. This year, when we have had such a moment of accountability, nationally Tsuru for solidarity embarked upon an internal conversation about anti-blackness in our own community and really the invisibility or erasure of our own people who are Afro Nikkei folks.

We are very connected to the Close the Camps, a campaign of Tsuru for Solidarity and we are connected to the Shutdown Berks Coalition. The Berks detention site is in Pennsylvania. It is one of three national family detention sites that exist in the country. In that particular site in the past two years, mostly black immigrants, Haitians have been imprisoned there. We’re working in partnership with Haitian bridge Alliance, Haitian voices, America.

Haitian Women for Haitian refugees and the Berks Coalition to really fight for their freedom and of families in detention, but also to uplift the narrative and understanding that a majority of refugees seeking asylum in us detention sites across the country right now are black immigrants.

It’s partly the endemic racism of the United States to erase this issue and continue to imprison black people in the prison, industrial complex, which includes detention and to turn away and not bring public awareness or understanding or decision to end this.

So our program this year, we’ll focus on uplifting the voices of organizers from families for freedom who are fighting deportations of many immigrants, but particularly black and Brown immigrants. Often people who have been caught up in the criminal justice system and have convictions and who faced deportation. We’re supporting Families for Freedom Haitian Women for Haitian refugees and Haitian Bridge Alliance who we work very closely with.

Miko Lee: [00:09:59] And what does that look like? Are you having an online celebration? Are you doing a safe gathering? What does it look like this year?

Mike Ishii: [00:10:07] In a year when the pandemic is raging, it’s very difficult for us to show up in solidarity in person at sites that require us to oppose them both mentally, psychologically, but also physically. We are going to stage an outdoors socially distance. Protest along with our organizing partners on the actual day of remembrance February 19 in Foley Square at noon on February 19th.

This is right in front of the ICE headquarters. It’s also in front of the federal courthouse. It’s also the site of the Memorial to enslaved people who were brought here against their will from Africa and who were buried in a cemetery in lower Manhattan in the wall street area that was then developed and of course commercialized, but at least there’s this one small area where there still exists a Memorial to these people.

Our communities are going to come together in opposition and resistance to detention. To the continual targeting and imprisonment and mass incarceration of black and Brown people in memory and holding space for the people of all our communities, including the Japanese-American community who have had people forcibly removed. Detained had their family separated faced deportations and mass incarceration.

Miko Lee: [00:11:49] Can you talk a little bit about redress and the connections to reparations for enslaved peoples in the U S?

Mike Ishii: [00:11:57] Tsuru for Solidarity has just finished a longterm planning phase. We’re only about a year and a half old and we came about somewhat by accident because a group of us were angry enough that we decided we would go to Texas and protest at the family detention sites. We also began talking about the need for a unified, progressive voice in the Japanese-American community that spoke out about a lot of issues, including reparations. We recognize that perhaps there was a role for us to play on the national stage supporting the efforts for HR 40.

We are just embarking upon opening up that work in the organization. We try to approach everything very really on a relational basis. We’re going to be spending the next period, building out relationships with the organizations that have historically mostly in the black community, then leading this long struggle for redress and reparations and who have really opened the way for an idea that that embraces.

Really a reframing, a revisioning and a repairing of the United States, a country built on enslavement and murder and kidnapping of people of African heritage and attempted genocide of indigenous people. We really have a sense that this is a really powerful sea change moment for the country. If there’s any way that we can use our historical narrative to support this work, we’re happy to do so.

Miko Lee: [00:13:39] I am wondering what your thoughts are around the best way to talk with elders about the internment without retraumatizing them. Do you have thoughts on that?

Mike Ishii: [00:13:56] I’ll tell ya my own mother wouldn’t talk about it. My grandmother talked more about it than my own mom would. I think when we approach conversations around the world war two incarceration, it’s always important to create a very respectful listening space. That gives the survivor, the option to share or not share.

In Tsuru, we’ve tried to create spaces where people can come and join healing circles, and that’s something they will opt into. It’s a very easy process to participate in, but it’s a self-selecting process. What I have seen in the last couple years is an incredible development and acceleration of a healing process with great sophistication across the movement space, around addressing trauma in our communities.

And so that we’re even asking questions, like how would you create healing spaces that don’t re trigger survivors? It’s an amazing advancement. It just says so much about the care and and respect and thought that’s going into tray in, into creating these healing spaces. I have found also that the survivors who have chosen to attend our healing spaces. And again, that’s, self-selecting they’re often very eager now to talk about it. I don’t know if that’s because they sense that it’s important for them to share their stories more publicly for institutional memory. It could be that I also think that the community is in a really the best place perhaps, ever to receive and treasure the stories.

I’m one of the older fourth generation young stains of the community. I’m in my mid fifties. And there are many who are, close to 20 years younger than me. For some of them, it was their grandparents who were in the camps and their families didn’t talk about the history. So there’s a sense for them of reclamation of family history or a narrative or connection to being Japanese American, that feels very important for them and how they approach. Creating space for elders has been really wonderful to observe and participate alongside with them. Just, by accident, having found myself in the middle of the city for solidarity work as a child, I wanted something around healing and I didn’t understand what it was. It’s why I became a redress and reparations activist as a older teenager.

And, then became involved with Yuri Kochiyama and NY DOR and, here, I find myself now in the middle of this work, it’s really maybe my lifelong hearts or childhood desire to find some meaning in the story and to contextualize it. But when we talk about trauma it’s intergenerational and I in doing the work with Tsuru more than ever, because I’ve had a chance to talk to many more people now and just be in conversation and meet many survivors, but also many descendants.

What I’m finding is that there’s just this deep sense of pain and loss. Sometimes when you can get to it deep terror that we carry as a community. In my own story my family was removed from the Seattle area and sent to Idaho to incarceration. But while there, my grandfather heard on the radio, a story of a Japanese American family in upstate New York who on Christmas Eve in 1940, cautions that I think 42 a white man who was a WW1 veteran entered their home and he shot them all and he killed my great uncle. My great uncles, mother and my great aunt survived. They almost died, but they did survive the massacre and their child who was mentally disabled, fled into the woods and was spared and found later by neighbors. But I live in New York. And especially after you see something like what happened on January 6th or hearing the stories of our people or IBS, the Burks Detention center in Pennsylvania. And we’re, we’re protesting outside the fences and we see the families come to the fence, the children run to the fence, because they see us coming to support them and demanding their freedom from behind barbed wire. It’s in those moments that you realize that we’re all carrying tremendous trauma in our psyches and our hearts and in our bodies.

And so the work of the healing circles in Tsuru for Solidarity and the conversations that we’re all having in the Japanese-American community right now about closing these detention sites that not one more family to be separated, not one more child being incarcerated. You don’t get to put people criminalized immigrants and put them behind barbed wire.

That’s just not okay. Okay. And we’re going to stand up against it and with these people and in doing that, we’re healing ourselves from this trauma.

Miko Lee: [00:19:45] Thank you for that. You spoke at the very beginning of this saying when you were in your teens and you became an activist, was there a particular event that was the catalyst that spurred you into becoming an activist?

Mike Ishii: [00:20:00] Yeah. Oh yes, there was. So my sister, who’s also a member of Tsuru for solidarity Leslie Ishi who is amazing performing artist. She is the artistic director of Perseverance Theater and has helped develop a lot of the performing arts direct actions and really helped choreograph the direct actions that we’ve done at the national protests in Oklahoma and Texas. When she first became an actress, she was part of the Northwest Asian American theater led by Nikki Lewis, who actually was with us at Fort Sill when we committed civil disobedience. Nikki is a survivor. Nikki’s staged a play called Breaking the Silence. It was a story about incarceration of the Japanese American community. I think it was 1981 and she staged a performance at the university of Washington in one of their large auditorium as a fundraiser for the coram nobis case and support that effort for Gordon Hirabayashi, who is of course, a son of Seattle and much beloved. I remember being a young teenager and attending with my family, because of course my sisters in the production. Sold out house. The entire Japanese community is there.

This is one of the first times that an event like this had happened and it was a very healing event and very emotional. I remember it, I’m there with my entire family. My grandmother’s there. My aunts are there, my siblings, my mother and father, my cousins, and at the intermission I go into the bathroom and all of the Nisei men are in the bathroom and they’re crying. They’re weeping. I was just, I was shocked. I didn’t know what to make of it. I didn’t under, I wasn’t old enough to understand it well enough, but I knew that they were survivors and I knew that they felt like they couldn’t show that kind of emotion publicly but they couldn’t help themselves.

It was just one of those moments where the dams broke open. I remember coming back to my family who are sitting in their seats and telling my. My mother and my grandmother and they were just, their eyes were wide. They were just, very emotionally moves and shocked by the power of that moment. That was my first connection to this work and it impacted me greatly. So I really bow deeply to Nikki Lewis.

Miko Lee: [00:22:34] Thank you for that. Is there anything else that you want to share about the upcoming event or the work going forward?

Mike Ishii: [00:22:40] Tsuru for Solidarity has just finished a five plus months Planning process. We had planned to do a very large demonstration and March on Washington demanding an end to family detention last June. Of course that had to be canceled because of the pandemic we’ve pivotted in that moment and ended a virtual program called Tsuru Rising. Close to 30,000 people participated in that a weekend online through our different social media platforms. We also did seven direct actions that were socially distanced across the country at detention sites and prisons. As a result of that, a weekend, we embark upon a community conversation series examining racism. Anti-blackness in the Japanese American community, looking at interracial intergenerational trauma and multi-racial history in our own community. We started embarking on a process to try to understand if the community felt that there was a role for Tsuru for solidarity going forward.

We want to develop more work in and to continue forward. So as a result, we have now emerged in 2021 with an 18 month plan to go forward building out our work in these four areas and where right as we come into day of remembrance this is actually the same time that we’re launching a new forward looking plan with an expansion of our presence and work.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:24:18] Thanks to Mike New York’s Day of Remembrance co-chair next up listen to New Years by Asobi Seksu

That was a Asobi Seksu’s New Years. Next up we hear about day of remembrance activities in Chicago from Miko’s conversation with co-chair

Lisa Doi: [00:26:02] Lisa Doi.

Lisa Interview

Hi, I’m Lisa Doi. I’m the president of JACL Chicago, which is the local chapter of the Japanese American citizens league, which is a civil rights organization. I’m also an organizer with Tsuru for solidarity, which is a national network of progressive Japanese Americans organized, particularly around immigrant detention and finally for fun. I’m also a PhD student in American studies at Indiana university.

Miko Lee: [00:26:31] What’s your personal connection to the internment?

Lisa Doi: [00:26:34] I’m a Yonsei and my grandparents and great-grandparents were incarcerated in rower, Arkansas.

Miko Lee: [00:26:41] How did you first hear about the internment?

Lisa Doi: [00:26:44] When I was growing up, I was really lucky to have grown up very much connected to the Chicago, Japanese American community. I sort of learned bits and pieces through going to events and being dragged to events as a kid. And through my mom’s oral history work in documenting the experience of Japanese American Chicagoans. In college, I had two opportunities back to back. One was a program run by JCL Chicago called the Contra project, which brings college age Japanese-Americans from the Midwest to mans and AR and little Tokyo. And then I also was able to take a class at my school on Japanese American incarceration history. And that happened within six months of each other.

So that really, opened my academic interest. I think one of the things I’m most disappointed in is that really, by the time I was able to be interested in this topic and ask questions on my own, my grandparents. Either had dementia and weren’t able to talk to me or had passed away.

I never really got the chance to hear my own family’s story. I think that’s one of the reasons why I’m interested in both academically and in an activist way of preserving and sharing the history of Japanese-Americans.

Miko Lee: [00:28:05] What are some of the questions you would have asked your your grandparents and have you had a chance to ask some other elders those questions?

Lisa Doi: [00:28:14] I wish I could have asked and I don’t even know that I would’ve been able to ask this because as I mentioned, my mom. Was it oral historian did a lot of oral histories with Japanese-Americans in Chicago. And as she was preparing for that she tried to interview her own mother and found it to be too hard to hear her own mom’s story, that it was easier to hear at a distance to hear about other people, but it was when it was this person who you had this intimate relationship with it, it became too painful. But I think I would have wanted to know how my grandparents felt. I also think that’s a question where I want to recognize that their feelings changed over time.

That. If I’d asked that question in 1945, I’m sure they would have given a different response than if I’d asked that question in 2005. I also think that it would have been interesting to be able to ask those questions to them over time. I haven’t asked that of anyone else yet. In some ways it’s a challenging question and maybe a little bit of an unfair question.

But I think particularly as the. Within the Japanese American community as this notion of intergenerational trauma becomes a more accepted notion and a more common topic for conversation. I think one of them, one of the struggles I have with it is I don’t necessarily know that my family felt traumatized.

Or perhaps I don’t know what that trauma visitation looks like. And so I think that’s one of the, one of the places where this question about, how did you feel about this? I think that’s where it comes from for me

Miko Lee: [00:29:56] Can you talk to me about day of remembrance?

Lisa Doi: [00:29:59] Day of Remembrance is a commemoration event that happens across the country, different cities do different things. It’s been happening for a few decades in Chicago, and we always try to commemorate the signing of executive order 9066 on a Sunday, closest to February 19th. And I think one of the additional things that’s important about DOR as it’s commemorated in Chicago is it’s always a coalitional event. So the event is always co-sponsored by JACL Chicago, the Japanese American Service Committee, the Japanese American Historical Society, and the Japanese Mutual Aid Society of Chicago. Having these four groups, which are good collaborators, but really intentionally co-sponsor this event with a rotating chair organization, I think is a statement about the central of this event within the Japanese American community in Chicago.

And really a chance for people who maybe don’t get to see each other often over the course of the year to come together and work on an event or attend an event and it really brings out lots of people within the Chicago, Japanese American community who might not otherwise come to programming and community events.

Miko Lee: [00:31:15] How are you adapting to this year of shelter in place?

Lisa Doi: [00:31:18] We are holding a virtual DOR event on February 21st, and it will be a live streamed conversation. Typically we hold our event at the Chicago History Museum. In 2017, which was both the 75th anniversary of the signing of executive order 9066 and the first DOR after Trump became the president. It was a unseasonably warm February day in Chicago, which was like 60 degrees, which is just unheard of we had, five or 600 people trying to come to this event in a theater that seats 250. So we ended up doing our DOR program twice with an overflow space and the Chicago history museum was kind enough to just let all 600 people come into the museum for free and explore the museum, even if they couldn’t come to the DOR programming. even before shelter in place. Our DOR program has really changed year over year and tried to be responsive to the moment.

Miko Lee: [00:32:21] So what does that look like for this coming year? How are you pulling everybody together online and how are you sending the word out?

Lisa Doi: [00:32:29] This year, our program features John Tateishi in conversation with two local folks from the Chicago area. One is an older woman from a suburb of Chicago called Evanston. And Evanston recently implemented a reparations bill, a local reparations bill, which redistributes cannabis tax sales towards redressing systematic and structural racism impacting black residents in Evanston.

It was actually the first city or city across the country to implement this kind of legislation. We’re really trying to tie the history of Japanese American redress, which is what John is familiar with to contemporary movements for reparations. The conversation will be moderated by Josina Morita, who is also an activist and community leader in the Chicago area.

DOR has a chance to tie Japanese American history to contemporary moments. This is just one more example of how we get to do that. We chose the topic of redress this year, because we’re coming up on the 40th anniversary of the commission hearings and Chicago was one of the testimony sites. Over the course of the year, we’re trying to think about the various ways we can use this commemoration, not just DOR, but commemoration events over the course of the whole year to have these conversations about why redress is a way to talk about reparations and why reparations are. An important conversation for our country to have now.

when we’re talking about reparations in Chicago, in this DOR, we’re talking, we’re tying Japanese American redress to African-American reparations today. In Chicago, it takes two forms. One is this this broader national move behind bills, like HR, 40 to think about how the us locally and federally can repair the harms of slavery and, be intentional about. Teaching that history, understanding that history and doing repairative work around that history,

Miko Lee: [00:34:32] Can you speak a little bit more about HR 40 and just describe it?

Lisa Doi: [00:34:36] HR 40 is a piece of legislation that has been introduced to Congress several times over several decades, it’s very similar to the bill that created the Japanese-American commission. And it really is just that it’s calling for the creation of a commission to study the history of slavery in the U S and think about how. Think about what reparations look like, think about what repair it looks like. And so it’s being re-introduced again in this Congress, or it’s likely to be re-introduced again in this Congress. And hopefully either this year or next year it’s a bill that can pass.

Miko Lee: [00:35:16] Why do you think it’s important to link the two horrific events in American history and UN in terms of redress?

Lisa Doi: [00:35:25] It’s really important to be able to draw parallels in historical moments without feeling pressure for comparison. I think Japanese American incarceration is a very different history than the very long history of slavery and Jim Crow and ongoing structural racism that African-Americans have whipped with for centuries. those parallels can be drawn without direct comparisons being made.

That’s really important to me. I think Japanese-American redress at this moment stands as the only example of federal legislation that attempts to redress a historical wrong. There could be and should be longer conversations about the limits of the redress movement and what repair for the Japanese-American community looks like.

Having Japanese Americans and Asian Americans more broadly support this movement for black reparations today is incredibly important and an incredibly important act of solidarity. Thinking beyond just the Japanese-American community, it’s important for people who might otherwise say my family wasn’t in the United States when this happened, or this is not part of my history to recognize that it is an issue.

Inevitably a part of American history. If you have any history within the United States, this is part of your history and you need to participate in the conversation is around this, and you need to be part of the conversations that are thinking about what to do with this history and how to repair this very long history of racial violence. For the Chicago day of remembrance program this year, you can join the live stream or watch the recording at: www.ChicagoDOR.Org.

Next up, listen to Stay Awake by Asobi Seksu.

Jeff Interview

That was Stay Awake by Asobi Seksu. And next we hear about Day of Remembrance happenings in the Bay Area through my conversation with with Jeff Matsuoka.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:39:14] So I was wondering if you could tell us a little bit about your personal connection to the internment.

Jeff Matsuoka: [00:39:19] I’m actually the the son of a Peruvian Japanese and she actually grew up in Lima, Peru, but something that’s not very well known is the fact that during world war two, the United States and Peru came up with some kind of clandestine agreement where by they were actually able to deport prominent Japanese Peruvians from Lima to the United States. It’s a pre rendition type of situation. My mother’s family ended up in Crystal City, Texas, which is the department of justice in terminal camp. That’s where she spent most of the war after the war.

They were people without a country. The Pervuian government, renounced their citizenship. So they couldn’t go back to Peru and they were not us citizens either. So the United States government tried to deport them to Japan, but my grandfather resisted and. Fortunately we were lucky to be able to be under the guidance of Reverend Fukuda here in San Francisco, the Concord church, and he sponsored my family and they met up with an attorney called Wayne Collins.

Wayne Collins is a famous attorney in Japanese American circles. He actually fought for the right, the civil rights of Japanese Americans during the war and actually, especially after the war. And thanks to Mr. Collins. My family was able to stay stay in the United States first as temporary residents.

They actually had to renew their residents every year, basically to, to stay in the United States. And finally, they were able to become released. My mother was able to become a naturalized citizen in any way. But yes, it was quite a quite an interesting story that my family went through.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:40:53] How did they share those stories with you? Was it something that was talked about at the dinner table, or did you have to ask them specifically about their experiences in the camps?

Jeff Matsuoka: [00:41:01] They didn’t really talk about it too much. When we were growing up, well, interestingly enough, they did have every five years or four years, maybe they actually had a reunion with other Peruvian, Japanese. One year they actually came to San Francisco and I met some of them. That was the first time I met some of my mother’s childhood friends. We talked about their association Peru, but we never talked too much about, how they came from prude to the United States.

When the redress movement began in, in the eighties. That’s the first time actually that many Japanese Americans, as well as my parents, my mother in particular. Started speaking out about her experience and that’s the first time that by the time I was in my twenties actually, but by that was the first time that they really publicly came out and said, talked about their experience in, in, in the camp.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:41:48] What was it like for you hearing that in your twenties and how did that shape your own understanding of your cultural identity?

Jeff Matsuoka: [00:41:54] I can’t really say it was a shock. As a kid you grew up and you hear things and you say, okay, something happened, but you weren’t really sure what happened. As I grew to maturity it suddenly not suddenly gradually dawned on me that, what had happened to my parents or my mother in particular in it. And her family was really quite. Unjust and, it was clearly a situation where through no fault of their own they basically suffered at the hands of both the proving and the United States government.

So that kind of increased my awareness consciousness of, what could go wrong basically in, in the United States. Yeah, of course I’m a United States citizens and I was born here and then I’d stays in my, which I privileged that my mother did not have. It really opened my eyes a little bit about what this country can do.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:42:39] Growing up in the United States, did you learn anything about Japanese internment or anything about Japanese Latinos that were interned?

Jeff Matsuoka: [00:42:46] I heard a little bit about the Japanese Americans being intrigued by. I never heard anything about Japanese Peruvians or other other Japanese, Latin people in interns. So that was news to me.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:42:56] And can you talk about the Day of Remembrance?

Jeff Matsuoka: [00:42:58] The first Day of Remembrance this was actually in 1979, just when you know, the Japanese American community started organizing for reparations. For many years, there was after the war, especially there was a sense of denial in the Japanese American community.

They wanting to live , go on with their lives and pick up their lives and not think about what happened similar to what my. My mother actually felt however, with the new generation the Sansei generation who had a, more of an appreciation for civil rights, there became a growing kind of consciousness in among the young people that, something had gone wrong during the war to our community.

That started the whole kind of activist movement here in the Japanese spare community, I began really in earnest in the, in that late seventies, early eighties. The day of remembrance was really the first kind of formal recognition of the fact that, we had to remember what had happened to ourparents and grandparents with the eye of making sure that, this type of thing would never happen again.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:43:59] Yeah. And going off of that, so much is happening now that really shows all that can happen in this country as well. I’m curious, how it feels for you and your family, seeing the children being caged at the border and other really extreme and inhumane measures being taken especially in immigration, but also in the carceral system?

Jeff Matsuoka: [00:44:19] The thing is that what’s happening at the border. And as far as separating families is really atrocious. Certainly in our experience, families were separated , but the children for instance, always were at least kept with their parents. the idea of separating children from their parents and putting them in cages is a simply, it’s a very barbaric act and that goes even beyond what we experienced. , it’s very upsetting to us, that it tells us once again, the importance of remembering history. Obviously people are not remembering what happened to us when they go off and do that without thinking basically or driven actually perhaps by the same forces of, racial prejudice that put us in the camps.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:45:00] And how is the day of remembrance different or similar in the various different regions of the US?

Jeff Matsuoka: [00:45:07] The Day Remembrance now it’s a nationwide activity. So you see this in many in fact, the most Japanese American communities in February, of course, February 19th is the day of the signing of executive order 9066. That actually committed Japanese Americans to be evacuated from the West coast in particular.

Certainly. If you lived in the West coast this is where of course this is where the majority of Japanese Americans lived at that time. That’s where, it resonates the most basically since we still have, even in our community today, we actually have people who were there, who were children, of course at the time, but they have the memory of being evacuated from their homes here in the West coast.

During the war is some the government actually offered for, to resettle certain Japanese Americans in Eastern cities like Cleveland or or Seabrook New Jersey, for instance, which had a farm that they needed laborers for. So that’s where the genesis of, the Japanese American diaspora. In these other Midwest or East coast cities. They were there mainly because it, executive order 9066, but their post-war experience is clearly different from those who came back here, to the West coast. The main theme of course, is the same, the fact that we want to remember executive order 9066 is in its aftermath. But of course, every local area has his own history and its own partnerships, for instance with other groups.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:46:36] How is it going to be different this year with COVID I assume safety protocols put in place and what can people expect and why is it important especially this year to be involved?

Jeff Matsuoka: [00:46:45] This year, we have decided to go to all virtual event on zoom. We have decided that we need to have more of a consciousness of the black lives matter movement. That of course very much came into prominence last year.

This year our Day of Remembrance here, San Francisco is it will basically focus on the interrelation between Japanese American and the African American community in San Francisco especially around redevelopment, as well as civil rights. This of course happened mainly in the sixties and seventies.

The history of course, is that in. . Before the San Francisco redevelopment agency decided to redevelop Japantown, the a or the Fillmore district the Japanese Americans and African Americans lived together because many of the Japanese-Americans the African-Americans of course came here during the war when there was need for labor at the shipyards here in the Bay area.

After the war at least some of the Japanese Americans came back to the Western edition. So we have a history long history after the war of living together harmoniously for approximately 20 or 30 years until redevelopment came along and threat to destroy, the neighborhood.

We saw common action with the African-American community. our keynote speaker, Reverend Arnold Townson is a, is very much an old timer from those days. He’s actually the vice president of the San Francisco NAACP, and he will speak to the common historical experience that the Japanese American and African American community felt, basically during that time of crisis as well, actually the civil rights movement during the sixties also of course inspired the Japanese American community to stand up for our rights as well.

So clearly, we owe a debt, I think, to the African-American community and we want to go back and explore those connections, as well as of course, stand in solidarity with the African-American community, as far as, all the issues, including reparations, of course, as the Japanese-Americans were fortunate to, to be, to actually gain reparations from the U S government.

Through the signing of the civil liberties act of 1988. We got an apology and we actually got a monetary compensation for the government. Now, the African American community also is looking for reparations in particular, the national bill, HR 42, as well, as there are actually are bills here in the state of California. Governor Newsome, for instance, recently signed a reparations bill for African-Americans to set up a commission to explore African-American reparations. In the city of San Francisco supervisor sham on Walton actually is going to introduce a resolution to set up a similar commission for African-American citizens here in San Francisco.We basically want to reflect in our experience of gaining reparations. The hope that, we could perhaps provide some lessons for our African-American brothers and sisters in their struggle for reparations.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:49:35] Speaking of, the Day of Remembrance as, and reparations as something that can be really healing, what are some other healing practices that you have adopted to heal from your family being interned and this history of them being kidnapped from their country?

Jeff Matsuoka: [00:49:48] I’d say maybe about over a year now, we actually, my family, at least my mother unfortunately passed away about almost 10 years ago now. But they never went back to Crystal City. They never want to go back to Crystal City after they were released from the camp.

But about a year and a half ago. We actually had a pilgrimage Crystal City. Internees as well as her family. It was quite liberating to go there with my family and spend some time. To see what the city was about or see what, how the camp felt.

Of course the camp has gone, but nonetheless, it was really nice to be there to, to be there. Basically , there was about a hundred people in this pilgrimage people, who descendants. Of course, many of them are descendants of a crystal city internees. So it was great to meet them , I was very impressed by the reception that we had from the city of Crystal City. The mayor met us and, the the Chrysalis city site now is next to the crystal city high school. So we had our lunch reception there.

They, the city had, or the school, the high school had taken out an exhibit basically of what crystal city looked like during the time where my mother was there, as well as they also collected pictures. Some of those pictures I’ve never seen before, actually of my mother , when she was a young, she was only about 14 years old when she was there.

That was really an eye-opener in, and it goes to tell you, that once again you really can’t forget your past and it was really . After all these years of not talking about it, it was really a revelation to actually be there and with a hundred other people and talk about, what had happened there and what the lessons are to make sure that something like that doesn’t happen again.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:51:20] Definitely. I’m so glad that we’ll have the day of remembrance to celebrate together virtually and get to learn across communities and build together.

Jeff Matsuoka: [00:51:28] I encourage everybody to join the day of rememberance ceremonies. it’s going to happen on Friday, February 19th, 2021. Actually the day of interestingly EO 9066 it’s gonna be from six to 7:30 on zoom it’s free. We encourage everybody to come in and learn about what happened to arc chappy, spirit, community and also what has happened in our interrelationships with the African American community and how we want to lift them up in their struggle for reparations.

Miko Lee: [00:51:54] So we have a whole episode dedicated to day of remembrance. I’m wondering what are your walkaways from these conversations?

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:52:03] I think they really highlighted the importance of solidarity. And of course, given the name, the importance of remembering. And how, particularly in the Asian American and Pacific Islander community. It might not be something that we’re culturally inclined to do. I think that was a really common theme of like people’s parents, grandparents didn’t necessarily want to talk about it until really see seeing why it was so necessary and that this is a part. Of our activism and our legacy in the con in this country needs to include making sure this doesn’t happen again and using our stories to make sure this doesn’t happen again.

Miko Lee: [00:52:40] I think the power of these family stories and how they carry on from generation to generation , is really impactful. And we could hear from. An episode a while ago, or She sees her father being incarcerated at the Smithsonian for the first time. To Mike, seeing the Issei men crying in the bathroom after seeing a play about their experience. The need to share these stories is so important and also so traumatic. And how are we carrying on that trauma from one generation to the next generation? I think that’s also the power of the day of remembrance.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:53:19] Yeah. And that sharing can be really healing, especially when it’s done collectively. And especially when it’s something that builds community around. Trauma and surviving from it and healing from it.

Miko Lee: [00:53:32] And we are living in trauma right now. And right now, when we were both on this call that was looking at the increase in anti-Asian hate crimes, which is up by 1900%. Which is just so vast in our time right now. And so scary. But even in that call, when the. You know, leader of Oakland black, Panther’s got up and said, “We need to work together. We will send folks out to the Oakland, China town to work and. And make sure that this kind of hate crimes do not happen again.” And when we see all of these day of remembrances across the country, even though the focusing on their own community, they’re all talking about building solidarity between African-American and Asian-American communities. And I think that’s really powerful.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:54:19] And I like that. That’s where the redress movement is going of like, okay, we got reparations. Let’s figure out how we can make sure you all are getting reparations to. And there was a bunch of specific bills that were mentioned tonight. , both. Nationally, but also regionally and statewide that are working towards that.

Miko Lee: [00:54:36] Yeah, I thought Lisa’s bill that she’s talking about in Chicago that really, really specific small bill is a really good model that other cities could be able to utilize to really start to do real reparations in their communities.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:54:51] And also just for our listeners out there, we know this material. It can be hard to digest and it can be really heavy. So we hope that you all are taking care of yourselves. And any ways that you know, how do, and that you need to take some time to yourself and reflect and process in any way that you need. But, you know, we do know that this is heavy, that it affects all of us and that hearing this stuff in this time can be really difficult and challenging. And.

I think it’s just a good reminder that we need everyone to be able to get to liberation and to be able to get to the kind of communities that we want to live in. And like Jeff was saying, this is an example of what this country is. And we’re seeing a lot of examples of the worst of what this country is, and it’s up to us too. Push this country through our communities to live up to the idea of what it could be.

Miko Lee: [00:55:50] We’re also seeing people intentionally doing these healing circles together and really utilizing. What has happened in the past to make sure that it won’t happen again, and it is a struggle and it is incredibly hard. But I’m for me in my lifetime, seeing people. Talking about working together for collective action for change. And a lot of our speakers tonight talked about different issues that deal with japanese Americans and the incarceration that happened in world war II and the impacts, and a lot of those issues we have dealt with, or we’ll be talking about in other episodes. So Jeff’s family, , is Japanese, Latin American, and we have a whole episode that will come on that next. And we have a whole episode that will also be on redress and reparations very specifically. So we hope you’ll stay tuned and join us on those

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:56:50] And check out our website for more information about day of remembrance events that are happening around the country. And if you feel comfortable coming out to the streets in person with covid safety protocols in place then those events happening in new york and an oakland chinatown to heal together and make our voices heard in this crucial time

Ending

Thank you to all of our guests on this episode, please check our website, kpfa.org/program/apex express for links to find out more about each of our guests tonight. We’re in the process of developing a study guide and online teacher training so stay tuned we thank the California Civil Liberties program for making this series possible.

Thank you for listening we’ll see you next time on apex express

Miko Lee: [00:57:35] keep resisting, keep organizing, keep creating and sharing your visions with the world. Your voices are important. Apex express is produced by Preeti Mangala Shakar, Tracy Nguyen, Miko Lee Jalena Keane-Lee tonight show was produced by your hosts, Miko Lee, Jalena Keane-Lee. Thanks to KPFA staff for their support and have a great night.