A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists.

A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists.

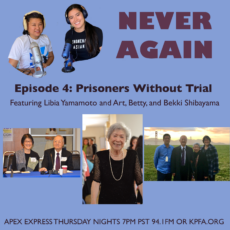

Tonight Hosts Powerleegirls Miko Lee & Jalena Keane-Lee continue their series Never Again with a focus on Prisoners without Trial, the Japanese Latin Americans who were kidnapped from their homes and held in American prison camps. Featured guests include the late Art Shibayama, his daughter Bekki and Libia Yamamoto who was abducted from Peru as a 7 year old child.

More information about what our guests talked about:

Japanese Peruvian Oral History Project

Prisoners Without Trial Transcript

Opening: [00:00:00] Asian Pacific expression unity and cultural coverage, music and calendar revisions influences Asian Pacific Islander. It’s time to get on board the Apex Express. Good evening. You’re tuned in to Apex Express.

Jalena: [00:00:18] We’re bringing you an Asian American Pacific Islander view from the Bay and around the world. We are your hosts, Miko Lee and Jalena Keane-lee the Powerleegirls, a mother daughter team,

miko: [00:00:28] Welcome to our new series, Never Again, where we will explore stories about the exclusion and detention of Japanese Americans during world war II. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, president Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed executive order 9066, which unjustly called Japanese Americans a threat. Over 120,000 Japanese Americans and Latin Americans were incarcerated for over three years. The majority of the Japanese American detainees were from the West coast where they had excelled and creating robust farmlands. Pressure from the white farm industry was a major factor in pushing forth the racist internment policy.

Jalena: [00:01:08] We will talk with surviving detainees about their experiences then and now as they continue to be active agents for change will also highlight the work of activists today many of whom carry their generational concentration camp experience into their advocacy for civil rights and civil liberties

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:01:25] tonight. I’ll never, again, we focus on prisoners without trial. The Japanese Latin Americans who were kidnapped from their homes and held in American prison camps. We speak with the late art Sheba Yama prior to his court case, before the human rights commission, then get a recent update from his daughter, Becky. We also talk with libya yamamoto about her experiences being abducted as a seven year old child so keep it locked on apex express

Miko Lee: [00:01:55] We had the opportunity to interview art and Betty Shibayama during world war II, 2200 Japanese Latin Americans. Kidnapped from their homes as part of a hostage plan of our us government, the government in collaboration with multiple Latin American countries arranged to have Japanese Latinos torn from their homes and brought to internment camps in the U S the intent was to trade these Japanese Latinos to Japan for American prisoners of war.

The majority of those were taken from Peru. And many Japanese Peruvians were very successful and they were specifically targeted for their success much like Japanese Americans in 1988, president Reagan signed the civil liberties redress act for Japanese Americans and provided those who were interned with an apology and $20,000.

However, Japanese Latinos were excluded. The government said that they could not receive redress because they were not citizens, a series of laws. Suits on behalf of these Japanese Latin Americans resulted in a 1998 settlement of $5,000 and a photocopied letter of regret. One of those families interned for years at a camp in crystal city, Texas was the Shibayama family.

Three of the Shibayama brothers, refuse to accept the settlement. In 2017, Art Shibayama represented the family and spoke before the inter American commission on human rights in Washington, DC. Right before they went to DC, we had the opportunity to speak with art and his wife, Betty. Art was taken from Peru with his family. 13 years old, his Japanese American wife, Betty was interned at several different internment camps. They shared their story with us.

Art Shibayama: [00:03:30] We were kicked out of there because my father had a good business . It was 1939. I think Prado was the president of Iran. At that time, he went to get rid of all the Japanese because Japanese were doing so good. , most Japanese were in business. Not like the U.S. Where they had a lot of farmers.

Miko Lee: [00:03:52] When you were at crystal city, did you hear about any of the other internment camps?

Art Shibayama: [00:03:55] Oh yeah, because they realized JA’s in there too. So we knew they had other camps.

Betty Shibayama: [00:04:04] In crystal city, it wasn’t like the WRA camps,

Art Shibayama: [00:04:07] I was five years deportation. And I was considered an illegal alien. I still got an, a nice invitation for the us army. So then since I was fighting deportation, I figured, Oh, join the army, or they will deport us.

Miko Lee: [00:04:26] What did it feel like working in the army for a government that had betrayed your family so much.

Art Shibayama: [00:04:35] I think I had no choice.

Betty Shibayama: [00:04:37] You’re supposed to be typing some top secret. So they wanted His officer wanted to know why he didn’t have citizenship

Art Shibayama: [00:04:48] One day my section leader there was a warrant officer warrant officers like a lawyer, they know army regulations inside out. And he says, I a, how come you’re a citizen? So I told him and he says, Oh, I get you one. So the paper, my paper went to Washington. Then they came back saying I was denied because I didn’t have a legal entry. No, the government brought us here, put us in the justice department camp, which was administered by the immigration. So how can that not be legal?

So then, so they advise me to go to the immigration after I got out of the service. So that’s where I went. I went there, to the immigration office. I says I just got out of the army. And they tried to get me citizenship, but I was denied because at the end of the illegal entry. So for now they don’t know what to do with me, because they never had a case like mine. So they say “you go home, we have to study your case. And then we’ll call you when it’s ready.” So then they sent me home and I waited a year and a half and they called me back and says, okay, everything’s arranged. You have to go to Canada if you’re Christian in Canada. So pick up a letter there.

So you’re able to come back in because I was illegal alien. So I couldn’t leave the country. So I went to Canada, I got the letter came back. I said, okay, here’s the letter so can I get my citizenship. They said, “No.” I said, “What?” They says, “we give you a green card, but for your citizenship, you gonna have to wait five years.”

Betty Shibayama: [00:06:42] And then he had to pass the naturalization test. That’s why on his record, it shows that his. Legal entry was 1956,

Art Shibayama: [00:06:52] 56.

Betty Shibayama: [00:06:53] So that will, of course, then he’s denied redress. He was like a man without a country, because Peru didn’t want them. And the U S wanted to send them to Japan? They didn’t want to go to Japan. So actually he was a man without a country.

Miko Lee: [00:07:10] So when the $5,000 settlement was offered to the Japanese, Latin Americans, what made you decide to opt out a settlement?

Art Shibayama: [00:07:20] Actually, we had a harder than than the JAs right? And they hear it. We only get a quarter. So I was like I say, it was a slap in the face and not only that, but the letter of apology, at least like hers, her letter of apology

Betty Shibayama: [00:07:40] on White House letterhead in his is just like a piece of paper. The, he doesn’t even mention Japanese or Peruvian.

Miko Lee: [00:07:54] What advice do you have for Muslim Americans right now that might be frightened about our current political climate

Art Shibayama: [00:08:01] Keep fighting. Speak up. If if you get a chance I hold back. Like we have to let the government realize that what happened to us can’t happen again.

Miko Lee: [00:08:18] thank you so much to the Shibayama family.

Jalena: [00:08:21] We’ll hear an update from art and betty’s daughter becky she beyond my next, but first listen to Kushi Modo boosty by Minio crusaders, a Japanese cumbia band

Welcome back. This is the Powerleegirls on apex express, and that was Kushimoto Bushi by Minyo Crusaders. Next up we hear from art and betty’s daughter Bekki Shibayama

welcome Bekki Shibayama to apex express.

Bekki Shibayama: [00:10:35] Thank you for having me.

Miko Lee: [00:10:37] Could you please share about what happened to your family, your father’s family in Peru in 1939?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:10:44] My father’s family was living very comfortably. They had a successful life in Lima, Peru when the U S government collaborated with the Peruvian government to capture and kidnaps some of the Japanese Peruvians, including my family for use in hostage exchange with Japan for our prisoners of war. Our U S government went into 13 Latin American countries and kidnapped people and brought them to the U S and put them in America’s concentration camps. My father and his family were captured and taken to a U.S. Army transport in Kao, which is the port city of Lima. They were shipped across international waters to the U. S. They arrived in new Orleans. Louisiana and on the way their passports and identification documents were seized and taken away from them so that when they arrived and were processed through U S immigration, they didn’t have any immigration documents. The U.S. Government used that as justification to arrest them and put them in concentration camps. My father and his family were put in the crystal city interment camp in Texas. They were imprisoned with other Japanese, Latin Americans, as well as Japanese Americans and people of German, Italian , and Jewish ancestry.

Miko Lee: [00:12:37] How long was his your father’s family incarcerated there?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:12:43] Japanese Latin Americans were held in the internment camp past the end of World War II and a lot of them remained for quite a while until they could receive sponsorship. Many of the Japanese Americans had left the camp and through the help of the civil rights attorney, Wayne Collins my family, my father and his family were able to get sponsorship from Seabrook farms and we’re able to stay in the United States. During their entire internment my grandfather had planned to return to Peru since he had obtained so much success there. But unfortunately Peru would not allow them to return. And since it was a war torn country, he decided he didn’t want to re turning to Japan. The only option left for them was to try to remain in the U S. They were really people without country to call their own. It was a very difficult situation for them. They didn’t speak English. Since my father had plans to return to Peru the entire time he didn’t have his children go to school to learn English in the internment camp, they attended the Japanese schools since he thought that they would return to Peru where people spoke Japanese. When they were living in Peru the Shibayama children all attended. A private school where Spanish and Japanese were talked. My father would explain that every other subject was taught in Spanish or Japanese and they learn both languages in that way.

Miko Lee: [00:14:29] So when did your dad learn English?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:14:31] He learned minimal English in crystal city. When they went to Seabrook farms I think that’s where he learned more English just by working with others. There are a lot of Japanese Americans at Seabrook farms.

Miko Lee: [00:14:47] Do you know about why Seabrook farms utilized so many interned Japanese-Americans

Bekki Shibayama: [00:14:54] It was because they needed cheap manual labor. They had heard that Japanese Americans were very hard workers and so it was to help fulfill their need for manual labor.

Miko Lee: [00:15:10] Your family in Peru was actually pretty well off, with servants. They’d lived in a big house.

Bekki Shibayama: [00:15:17] Yes, that’s right. So they had a very large home where they even had they even had a large, real for, to hold dances because the family enjoy ballroom dancing. So my father’s grandparents were very good ballroom dancers and then my father’s mother was also a great ballroom dancer. They held dances at the house, with a band. They had maids and a chauffer.

Miko Lee: [00:15:48] So when the family was kidnapped, did all of that disappear? Did it go into a trust or what happened with their ownings in Peru when they were kidnapped?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:15:58] they lost everything. They lost their business, their savings, their cars, their home Yeah, everything was lost.

Miko Lee: [00:16:09] In California, corporate farmers fought for the internment so that they could have financial gain. Was that a similar situation in Peru?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:16:18] Yes, so that’s true. They viewed the Japanese Latin Americans as competition. Since the Japanese were successful there are many small family businesses that competition for them. Was discrimination where the Peruvians felt threatened. There was even a riot prior to world war two, where some of the Japanese, Peruvian businesses and homes were vandalized.

Miko Lee: [00:16:53] Your dad’s family moved to New Jersey. And how long were they there for?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:16:58] They were there for about two to two and a half years until my grandfather received a sponsorship from a friend who was living in Chicago. And when he received that he moved the family to Chicago and

Miko Lee: [00:17:18] your mom is Japanese American. So she, Betty has a very different incarceration story.

Bekki Shibayama: [00:17:25] My mother and her family were living in hood river, Oregon where my grandfather had a farm. He had pear and Apple orchards. They went from Pinedale to Tuli Lake and then from Tuli Lake, they were transferred two Minetonka.

Miko Lee: [00:17:45] How did your parents meet each other?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:17:47] they met each other in Chicago. There were Japanese American social groups that were started after the war. They met at an event at a bowling alley.

Miko Lee: [00:17:58] How did you hear about both of your families experienced during world war II?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:18:04] I heard about my mother’s story because her parents stayed with us. My grandparents, at the dinner table started sharing stories about, about hood river and then about the concentration camps. My mom would share stories as well. and My father kept quiet. And since, you know, since it was my mom’s family, I really didn’t learn the details of my father’s story until I was in seventh grade. I did an oral report on my father’s side of the family. I interviewed my father and my aunt. I asked them a lot of questions and that’s when I really understood what happened to their family.

Miko Lee: [00:18:54] What surprised you about that?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:18:58] I was shocked that that the country that I was born in and grew up in would do something like that. We’d go into another country and take people, kidnap people from their home and imprison them and then just leave them without a country. I thought we had freedom and that justice always prevailed and , that this was the ideal country to live in. After hearing about this, that I felt very insecure. I just thought how do I know that this won’t happen again? That we might be put in concentration camps again. I just remember feeling very vulnerable after learning about it.

Miko Lee: [00:19:46] Did you share that with your family?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:19:48] I might not have shared it with my father because I didn’t want him to feel bad. I started thinking that I know my father’s family had this gaiman attitude where, they’re just very resilient and they wouldn’t want us to be burdened with what had happened to them. I’m pretty sure I didn’t share my feelings with my dad. I would have thought that he would have felt bad if I told him how I felt. I told my mom. Most likely she, tried to reassure me. I still feel like we have to always have to be vigilant. Things like this are still happening today. So we still have to be aware and stand up and speak out for other community groups that are being targeted.

Miko Lee: [00:20:39] Do you remember when your dad and uncles first started talking about pursuing the court case for Japanese Latin Americans?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:20:50] After the civil liberties act of 1988, when the Japanese Peruvians were deemed ineligible for redress, because they were not us citizens or permanent residents at the time. I think that’s where my father and his brothers decided to continue to fight for justice. It was really important for my father that the U.S. Government acknowledge what they had done to the Japanese Peruvians and he wanted full disclosure of the facts.

Miko Lee: [00:21:28] Can you talk a little bit about the court case, how it started and then where it’s at now?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:21:34] In 2003 my father and his two brothers submitted a petition with the Inter-American commission on human rights pursuing The official apology and reparations from the U S government for the war crimes that they committed during world war II. They went to the international arena because they weren’t able to receive justice through the U S courts. Cases where either denied because of technical reasons or because the us claimed that they were in the wrong court. It wasn’t until 2017 that we were notified that there would be a hearing. The hearing was held in Washington, DC in March of 2017. For the first time, my father was able to testify about the war crime set. We’re committed against him and his family. In 2020, we were notified by the ICHR that they were ruling in favor of my father and his brothers. They recommended that the U S provide reparations And that they should provide full disclosure of the facts. We were asked to keep it confidential because the U S government was notified at the same time. They were given time to respond. But theU.S.Government did not respond. So the ICHR notified us that they were going to publish the ruling.

Miko Lee: [00:23:09] So the ruling is official and now what is being done with that?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:23:13] Our next steps is to try to get a meeting with the Biden administration. We’d like to educate Congress on what happened as well.

Miko Lee: [00:23:23] I heard you and your mom speak right after the crystal city pilgrimage, can you share what it felt like for you to go there? Was that your first time going to crystal city or had you been before.

Bekki Shibayama: [00:23:34] Had gone as a family with my father previously to the crystal city internment camp. It was during a Japanese Peruvian reunion. We all met there. So that was special to go there with my father. And to be able to ask him questions. And then last year we went to the crystal city pilgrimage? It was really the first organized crystal city pilgrimage. Although my father wasn’t there, it was very special for us to go because we felt close to him by being there. It was a very loving and healing experience and we just felt a great sense of community there.

Miko Lee: [00:24:17] Were there any stories that arose from your dad that stand out to you?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:24:21] The story that stands out the most is when they arrived here in the U S in New Orleans, they were led to a warehouse and they were forced to strip naked. They went through this warehouse where they had showers and then they were sprayed with it DTT. That story sticks in my mind because my aunt told how humiliating it was and how she felt so bad for the issei women , because they’re so modest and they had to strip like that. It was just very humiliating experience. The women and children were led through first and then the men were led through

The other story I recall was he would talk about the ship. When they were on the U S army transport, they were guarded with soldiers, with machine guns and whips. He vividly recalled that. The family was separated. My father was 13, so he was with the men. They were kept on the bottom of the ship and they were separated from the women and younger children were kept in cabins. His mother and the youngest children were put in a cabin with another family. My father remembers, they were only allowed onto the deck twice a day for 10 minutes. During that whole trip, which took 21 days, the family was separated and they weren’t sure if they were ever going to see each other again. That experience was, very frightening and also for my grandmother and the younger children because they also didn’t think that they would see my father and his father again,

On the site of the former crystal city interment camp, there’s a high school there. The high school students put together a display and they had, they printed photos of the internees and of the camp itself. So as we were walking through the display, with other incarcerees they were just, like pointing out my dad then when they saw my dad’s photo, some of them would point and they were, telling stories about him so that it was just really nice.

Miko Lee: [00:26:40] So there was, bit over 2000 Japanese, Latin Americans that were interned what is it that you think about your dad and his brothers that sparked them to pursue the case?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:26:53] It was my father’s determination to hold the us government accountable and to be receive an official apology and acknowledgement of what they had done and full disclosure. He convinced his brothers to pursue it along with him. He was determined that no other family go through the same experiences that his family had to go through. So he said he would continue as long as it took to find justice.

Miko Lee: [00:27:30] So this year in the Bay area, on behalf of the campaign for justice free dress now for Latin Japanese Americans you are being honored with the Clifford Uyeda peace and humanitarian award. Can you talk to me about the significance of this award to you and your family?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:27:48] It’s a very big honor to receive this award. Especially. Based on its namesake, Clifford laid at and all of his activism and fight for justice. And it’s just nice to receive an acknowledgement for the campaign for justice for all of its persistence and continuing fight for justice.

Miko Lee: [00:28:15] How do you think we can apply the experience of your family with redress to other communities?

Bekki Shibayama: [00:28:21] It’s important to hold the U S government accountable for its wrongdoings. I hope that this favorable ruling can help lead to Other justice struggles having favorable Willings as well. I hope that they can refer to this ruling and then it can help. It’s just us hope that with this new administration and it’s rhetoric around unity it gives us hope that that we can all fight for justice together, And I think for us at campaign for justice, we’re very hopeful that other community groups can lend us support while we also support other groups with their justice struggles.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:29:13] Next step we hear Arzu Ben Daisy. Daisy and by Minio crusaders from the album echoes of Japan.

Miko Lee: [00:31:14] We are back that was Minyo Crusaders’ Aizu Bandaisan from the album Echoes of Japan. Minyo Crusaders mixes, traditional Japanese folk songs with Latin music. We spoke with Libya Yamamoto. Libya was born in Chiclayo Peru and at the age of seven, she and her family were abducted and incarcerated at the crystal city internment camp in Texas. After release from camp, her family eventually resettled in California. She is a founding member of the Japanese Peruvian oral history project. She’s trilingual in English, Spanish, and Japanese and lectures often about her internment experiences.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:31:52] We’re really excited to talk with you, especially for this episode that we’re doing, which is all about Japanese, Latin Americans and experience with internment. So I was curious if you could tell us a little bit about your experience being interned and leaving Peru.

Libia Yamamoto: [00:32:07] In Peru, all of a sudden in 1943, early in January, my father was picked up with no explanation. He and a group of Japanese men were put on a truck and taken away without any explanation. We didn’t know where they were going for how long or anything. We watched them leave and wave goodbye, but we couldn’t do anything but to wave goodbye from about 70 feet away. I was very close to my father. And so to me, that was really traumatic because every time he went on a business trip, he would tell me where he was going. How long he was gonna be gone. What time, about what time he was coming home. I thought he was coming home by bus or car.

If he was coming home by bus, I would meet him at the bus stop and all this was pretty much in detailing and that morning. He was, he was so far away. I didn’t even get to hug him goodbye. In Peru we didn’t shake hands. We hugged, everything was embraced, but we, I couldn’t even hug him goodbye. All I could do was just wave from a bus, every seat away, just wave and wave goodbye and watch him go. Six months later in July we were told that we have to leave our country, our home and get on that ship in Callao. So we traveled 400 miles south to Lima and stayed with friends for about a week.

We got onto the ship and going up the plank. I saw soldiers lined up the plank and they all had guns. I thought, Oh, for sure, they’re gonna kill us when we go out on high seas and get going. It was really frightening for a child. I was seven years old and my mother and my sister and my younger brother, we were frightened. I had an adopted sister who also came with us and she had two children. She brought her children with her and. it was really frightening. When we got to Panama, we heard a lot of , hustle, and bustle outside of the ship. we were all told to get in our cabins and we were confined to our cabin. I got all of the kids on the upper bunk of the bed in our cabin. We looked out the portal and we saw a lot of soldiers running back and forth and just running back and for a lot of activities and pretty soon somebody came and closed the port hole on us.

We were disappointed and that we couldn’t see anything. Once we left Panama, there was a storm where everybody got seasick and one morning, my mother and I were brave enough to go to the cafeteria for breakfast. There was lady that was always very meek looking, very weak looking. She was there having breakfast. So my mother and I joined her, let us, and as I started eating, I started getting sick. I had to run to my cabin and gets you seasick the rest of people.

I arrived in Louisiana, in new Orleans when we got off there. They were inspecting all our thing belongings. I had to watch our personal belongings because my mother had to take my brother to the restroom. I watched the inspectors inspecting somebody else’s and they will throw away. they were throwing things that were Japanese because they did not want any influence of the Japanese in their lives. They were throwing things into the water and I would see them floating and in the little canal. I would want to be protective of my things.

There was one little doll that my father had brought home from a business trip when I was in a hospital. I had to spend my fourth birthday in the hospital because I nearly died from typhoid fever and I was in the hospital for about four months and he had brought home a souvenir of a Cupid doll and that it was such a cute doll and it was so meaningful to me. When my mother said you could bring one thing I brought that so when the inspector came by, I was hoping that he wouldn’t touch that. And I was worried. The inspector just put two his fingers through everything and didn’t take anything out. I was so relieved.

I remember my heart dropping, but there was a new beginning in the United States. We were taken to a big hall later, a university. This hall hadrows and rows cots lined up for a couple of hundred people. We worked really stay there for a few days. Outside, there was a little hill mound with beautiful green lawns. I was really impressed by how beautiful that was. Then we were put on a train to San Antonio, Texas. We never rode on a train like that before. We had to stay overnight on that train. The next morning my brother and I went to the car where they serve food. We had breakfast there bowl of something with a spoon. And so we took a little bite. It was so awful, so tasteless and so we couldn’t eat it. And we put that aside and resorted to having an orange for breakfast.

After we got to San Antonio, we were transferred to an old school bus. My mother said we were going to be a united with dad oh that was so exciting for me. I was so excited that I couldn’t wait to get to crystal city and but that ride was three hours long. When we got the crystal city we were met by kids who were in uniform and later I found out they were Scouts from the Japanese American group. They were adults there. I looked all over for my father. I couldn’t see him. Then they assigned us to our cabin and we went to a cabin.

I looked for my father there. I couldn’t see him. I said, “where’s dad?’ And mother said, “he’s not here yet. And he is going to be joining us.” for the next few days, I waited for him. The fifth day he showed up and, Oh, we were so happy. My sister, my brother, and I ran to him and we hugged him and just smothered him. My sister noticed that he had lost a lot of weight and it was quite skinny. And that didn’t seem to matter to me too much because I was able to see him. I was so happy that was our first, a week of a week in the United States and right into camp.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:40:20] Thank you so much for sharing. What was it like for you adjusting to living in the United States and living in the camps, especially as it came to language? Cause I know you spoke Spanish and Peru.

Libia Yamamoto: [00:40:30] Yes. We had to go to Japanese school. Shortly after we arrived, there were people from Peru coming all the time. The last group came in 1944. When we got there Japanese school started and I had to be in the first grade because I had never had Japanese school everything was a Japanese style. We have all lined up in front of single file in front of the door. Then we had to say an oath ” I am Japanese. I am small, but I am a Japanese national” in Japanese. We said that. Then we would go to our room. Then we in Japanese style that the doorway, we would bow to the classroom .

Then we would sit down . When the teacher came in that pass monitor would say rise and we all arise roles. Then he would say, bow, we all bow to the teacher. Then he would say, sit. And we all sat down to our desk. That’s the way that schools began in Japan, because that’s the way we learned to do in Peru, in our Japanese school, in Peru. Everything was very Japanese style. And so that’s where I learned Japanese. I went to the second grade in 1945, the war ended, and the government said no more Japanese school. So we had to stop Japanese school. Then we waited for the orders and the government had actually told us brilliance to go back to Peru or go to Japan, whichever one you want to go. We went to the United States by order of the government. And yet they told us we were illegal alien, so we had to leave and Peru will not take us back. We were to go to Japan Because Peru would not take us back. We’re ready to go to Japan and started shipping our trunks to Japan and we could just keep what we could carry.

Then that stuff, few weeks we waited to be sent to Japan, but the day before we were to leave. My father got very sick and he ended up in the hospital. So we couldn’t go to Japan. My married sister and her family went to Japan and my uncle and aunt who were from Peru came with us. They went to Japan. We said goodbye to them and all of our friends that we had met in camp, they went to Japan. We said goodbye to them. And we stayed on not a couple of years in camp.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:43:33] When was the time that you first returned to the camp as an adult after being interned?

Libia Yamamoto: [00:43:38] There was Association called crystal city association. They had a reunion going to crystal city. We met them and we shared information and we would join them in going to Crystal City . Of course, nothing was left. All the buildings were gone. They were replaced by newer homes.

We had an organization called Japanese, Peruvian oral history project, and Grace Shimizu, who was in charge of that. She was born here in the United States, but her father was in Peru. She wanted to record some of the people’s side experiences . So she started this organization and we started to plan the reunions that retraced our steps. We went to new Orleans and took the train to San Antonio, and then I arranged for buses to come and pick us up at the train station and take us to crystal city. And that was in 2001.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:44:52] How did it feel to go back and also to re to reconnect or potentially connect for the first time with all these people that shared that same experience with you?

Libia Yamamoto: [00:45:02] Oh, it was really great to see them. And of course, some of them, I did not know. And so it was nice to see, to meet and someone, but it was really good. There was a sense of camaraderie among us. The fact that we all came from Peru made a difference. We all had a similar experience. We all spoke the same language. So there was a sense of closeness and togetherness.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:45:35] What inspired the crystal city pilgrimage. That’s been happening the past few years and never again, pilgrimage with two for solidarity

Libia Yamamoto: [00:45:43] Victor Uno, his grandfather was in our camp and his grandfather was one of our English teachers. Victor had a group that he started. As a Crystal city pilgrimage group. He invited me to the planning meeting. And so I participate in the planning of their pilgrimage. In November last year, we went to San Antonio and now we had. Yeah, educational panel discussion. On Saturday we chartered buses so that they could take us to Crystal city. We had a Memorial service for the two girls there. We were available to reply to the school which wanted somebody to come and talk to their students. Kids in crystal city did not know that there was an internment camp right across the street from them, but they had heard about it because we were coming for the pilgrimage and I use in their high school cafeteria for our event. They wanted to know a little more about the internment and the Peruvians. The whole school had their Assembly and in the auditorium , the three of us spoke in our experience, shared our story with them.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:47:14] I love that storytelling and continuing and sharing the knowledge with the next generation and kind of in that same vein, I’m curious what keeps you going as an activist and keeps you, out protesting and organizing with and around crystal city.

Libia Yamamoto: [00:47:30] Just society. I think the Japanese Americans should talk more about during internment. We have a story that not very many people know that happened. It all started with the us government thinking about what to do with it. With the enemy aliens in the United States, we started way back in 1937. We weren’t even at war. They were already thinking what to do about the enemy aliens. Of course, at that time they didn’t know Japanese were the enemy. I think the story of the Peruvians is. Much less known. And in fact somebody said you only 5% of the United States citizens know about the internment. Now I think it’s more. It was fear that put us to camp because we are from another country, I just feel that people should know about these things as part of American history.

Miko Lee: [00:48:35] The other question I have for you is. In the last, crystal city pilgrimage . You talked a lot about how at the age of seven, you were kidnapped. I’m wondering what your thoughts are seeing the seven year olds, kids that were down there in the detention center where the protest happened and what were your feelings about that?

Libia Yamamoto: [00:48:55] There was a detention center called Dylan, about a hundred miles from San Antonio where central Latin American kids were separated from their parents and put into this detention center. If I had seen them, I would’ve cried because even the thought of it makes me cry. I feel so sad. And could feel because of the separation from their parents, like I could feel the way that I felt when my father was taken and we were separated. It’s awful feeling. And I remember feeling abandoned and I think these kids are probably feeling that too. I have so much compassion for them.

Miko Lee: [00:49:50] How important is redress and apology? What does that mean to you?

Libia Yamamoto: [00:49:55] It’s very important. It seems so uneventful at this time because it happened so long ago. But to me, that act was so bad and so unnecessary that I really feel the United States has to apologize because it really. degraded our position, to be brought here is like prisoners, like people who had done something wrong and we had not done anything wrong and we were treated like criminals, and that is beyond a apology, the least they could do is apologize.

Miko Lee: [00:50:38] Did Peru ever apologize?

Libia Yamamoto: [00:50:41] Yes, I think they, they apologized and they offered money too, but not to individuals. They did it to the Japanese community as a whole. In Lima they built a sport center and an auditorium and a medical unit with that money. When I went to Peru in 1990 and 1995, they took us around and showed us The sports center and theater and they had a small museum and they had a lot of rooms where the kids could come and do their homework. Then the medical unit where the people could come together health checked, but a lot of the Japanese didn’t come there. Most of the patients were for Peruvians who couldn’t afford to go to the hospital and they would come to the medical center. That was so the thing that they had done.

Miko Lee: [00:51:46] Thank you so much for spending your time with us and sharing your personal stories. We really appreciate it.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:51:51] That was activist Libya Yamamoto. It was such an honor getting to speak with these active elders about their experiences. And it’s really such rare stories to be told and shared. Even as I was talking with my friends about the show that we were working on, none of them had heard about the Japanese Latin Americans and how they were kidnapped from their countries.

Miko Lee: [00:52:10] So why do you think this story has been such a missing part of the Japanese American incarceration experience?

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:52:17] I don’t know. I think, similar to what Becky spoke about, is it really disrupts people’s understanding and idea of what America is? Not that Japanese incarceration doesn’t do that, but I think it brings it to perhaps a new level when thinking about people kidnapped from a different country and being without citizenship.

Miko Lee: [00:52:36] One of the other things that really stood out is the fact that the Japanese Latin Americans were left out of the reparations, the initial round of reparations. And it’s quite interesting because in our next episode on reparations, we actually speak with the author of a book about reparations, John Tateishi. And he was saying that they. Initially, we’re going to include the Japanese Latin Americans, but then it was very tricky to make that argument fit with their argument about citizens don’t deserve this. And so they thought, Oh, they’re going to do the first round. That’s just going to be focused on Japanese americans so that they can talk about citizenship and how of your citizenship, that should not happen to you, but then they never got around the JACL Japanese American citizen. We’d never got around to the next round at that point of including Japanese, Latin Americans. So once again, they’re left behind.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:53:29] I thought it was also interesting what Libya talked about with Perus reparations and how they did it instead of to individual families. It was more community-based to creating these community health clinics and sports centers.

Miko Lee: [00:53:41] I thought that was interesting too. I was astounded about the kind of details that Libya remembered from her childhood and how, and this is the such clear memories of things that happened on the ship and how she felt. Very clear and vivid memory. She shared her doll. I could picture that dollar. She was talking about it. .

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:54:04] It just goes to show the importance of memory and the importance of cultural barriers like her to tell those stories and also, how difficult it is to share that kind of. Part of your history. And I know that’s a question that we always ask, like when did you first hear about that for people who it didn’t happen to directly, but for descendants. And I think that’s a huge thing in our community that we continue to grapple with of, being able to talk about things that are hard and things that are painful and what that means and how we remember painful parts of our history.

Miko Lee: [00:54:37] And how do we continue to tell these stories? And remember, without retraumatizing those people that experienced it, that’s something that puzzles me and has sat with me after we’ve had these conversations with, okay, it’s so painful. And there’s so many things that are happening in our world right now that make that pain even more cutting.

Jalena: [00:54:57] Yeah. It made me think that it’s about time, that we all divest from this idea of America being anything close to a dream and start really focusing on dismantling this state and figuring out a new way to go about things that isn’t under the veil of America and American imperialism.

Miko Lee: [00:55:15] There’s so many atrocities that this country has done and is continuing to do. As we record right now, we’re still, there’s still the kids that are locked up in the camps that she is talking about and that the elders are still fighting against. That’s still going on right now. It strikes me that this story being so left out and so many other stories that are left out of our history. I went to San Francisco state and took tons of ethnic studies classes and did not hear about this until a few years ago through apex express. So how is it that folks that are even within activist circles that have had ethnic studies are not getting a full picture? I think that’s our quest is how do we share these stories? How do we let more people understand what has been going on? What continues to happen?

Jalena: [00:56:06] And what does it mean to reclaim history and to write it for yourself and to make sure that these kinds of narratives are known and are told, and I think. I mean talking again about culturally, the way that we are around our pain and our stories about pain and how oftentimes are there things that can be kept really hidden away and kept secret or even like Bekki was talking about how she didn’t want to tell her dad how sad she felt, because she didn’t want to make it even harder on him. I think this is like a reoccurring thing for us culturally. Like you don’t want to express. Your emotions. Cause you’re worried it’s going to make someone else’s emotions, even worse or someone else’s sadness, even worse. And hopefully like with the newest generation, we can try and break that. And really in our family, you have done a great job at this, but be the culture bearers and the people that are asking about family history and personal history, because that’s how we find out about these kinds of things.

Miko Lee: [00:56:55] In this time where there’s so much Asian hate crimes, we’re also just talking about who are the heroes of our past and how do we stand up and stand with our community. And part of that is understanding some of the painful things that we went through.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:57:10] Thank you to all of our guests on this episode, please check our website, kpfa.org/program/apex express for links to find out more about each of our guests tonight. We’re in the process of developing a study guide and online teacher training so stay tuned we thank the California Civil Liberties program for making this series possible. Thank you for listening we’ll see you next time on apex express

Miko Lee: [00:57:35] keep resisting, keep organizing, keep creating and sharing your visions with the world. Your voices are important. Apex express is produced by Preeti Mangala Shakar, Tracy Nguyen, Miko Lee Jalena Keane-Lee tonight show was produced by your hosts, Miko Lee, Jalena Keane-Lee. Thanks to KPFA staff for their support and have a great.