The digital audio sphere is a wild frontier of music rights, and it seems like anyone can get away with using anything. At some point, though, some music exec could activate an AI that recognizes the wave patterns of copyrighted music in podcasts, then demands that the file be removed from the internet. YouTube already has something like that in place. So how can a digital radio producer stay above board without foregoing rent, making sound-rich stories that can remain available online into perpetuity? Glad you’re here.

♫♩How to find it ♪ ♫

For pay:

Often, $20 can help you filter out a lot of unusable media, saving you time, and $50 or $100 can subscribe you to a library of decent material, none of which requires you to give credit to the artist.

Sound of Picture is a standard go-to (much of this artist’s music is also available via creative commons, see below), and there are plenty of other pay-to-use services like Pond5, Audiojungle, PremiumBeat, and StoryBlocks. Your best strategy here is to choose a service you like (their library, look-and-feel, navigability, and values) and stick with that company. Thanks for supporting music with your money!

Scroll down to see how to weave this music into your story.

For free:

There are three routes* toward free legal music in digital media:

- You can use anything that’s in the Public Domain. This is mostly pre-1924 music — just make sure the performance/recording is also in the public domain.

- You can get written permission from a copyright owner. Email is fine if it’s an original composition and original recording; things get trickier when you start dealing with record labels and/or multiple creative collaborators. Here is KPFA’s official form for music permissions.

- Then there’s Creative Commons. The rest of this post, including the following video, helps you navigate the Creative Commons and make use of the music in your radio piece. Thanks for humoring my ~creative~ heading.

♬♩Strategy of the Commons ♪ ♫

Below is the zoom demo I did on July 10 for KPFA producers, and here is a secondary (shorter) demo, using similar-but-different source material.

In the US, if you make something and release it under your name, you more-or-less have an automatic copyright on it. Go you! This is great for encouraging people to share what they make, with less fear of someone else stealing it, but it’s not great for promoting a culture of people making new things out of each others’ works. That’s why the Creative Commons was developed.

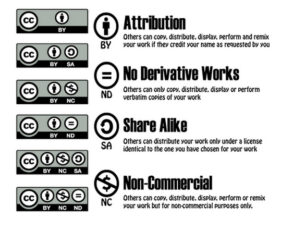

There are several CC licenses, starting with the “Attribution license” that allow you to share without limit, as long as you credit the artist. Here’s an explainer:

Other CC licenses limit how you can share the work, eg whether you’re trying to make money or whether you let other people share your work. To make sure you’re in compliance, develop a way to give credit to the artists (eg at the end of your program and/or in a caption next to the download button), and avoid CC music that has a “no-derivs” tag if you’re planning to do anything except share the entire piece, as-is, beginning to end.

“Ok but where is the ♫music♬”

Glad you asked.

This blogpost is a goldmine. It includes anything I could have thought of to share with you (even Soundcloud’s tucked-away CC search feature) and much more. During our zoom call, Laura also pointed out this youtube audio library, also a great resource. As you search for music, keep a few things in mind:

- Give yourself time to peruse.

- When you find something you like, save it, including the artist’s name, even if it’s not immediately useful.

- Enjoy the process.

*This post is about using music to complement your radio pieces, called “scoring.” But say you’re making a piece about Harry Belafonte’s 1988 Zimbabwe concert. This directly comments on specific music as a component of the story, which is different. In these cases, you can legally use copyrighted music under the fair use clause. Yay :D.

♪♫ How to weave it in♩♬

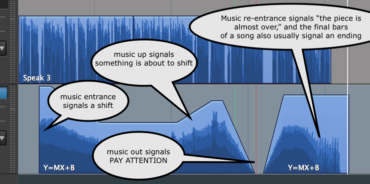

Generally speaking, you want to use music to signal transitions, so that the listener can be more oriented, less surprised if something changes or ends.

Here’s a quick explainer, pulling from the video posted above:

I wish you so well in your sound-making journey!

Will Rogers studied film at Stanford then gravitated toward the darker side of stories: audio. He has facilitated storycrafting among high school students, college students, and corporate teams. He’s now making moon art, studying the bonds between story & health, and remembering to take deep breaths.