By Lucy Kang, with help from Amanda Bloom

KPFA News

December 20, 2018

This is Part 2 in a series exploring the influx of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border in Tijuana. Check out Part 1 here.

The current American legal framework on asylum and refugees has its roots in 1975, when the US withdrew from Vietnam. Hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees fled forces the US had been at war with and came to America. A few years later, Congress acted.

“So today the law that we deal with is the 1980 Refugee Act which is embodied in the immigration laws,” says Bill Hing, a law professor of the University of San Francisco, where he directs the Immigration and Deportation Defense Clinic.

The 1980 Refugee Act opens like this:

The Congress declares that it is the historic policy of the United States to respond to the urgent needs of persons subject to persecution in their homelands, including, where appropriate, humanitarian assistance for their care and maintenance in asylum areas, efforts to promote opportunities for resettlement or voluntary repatriation, aid for necessary transportation and processing, admission to this country of refugees of special humanitarian concern to the United States, and transitional assistance to refugees in the United States.

“The law’s very clear,” says Hing. “You can apply for asylum irrespective of how you come into the United States. It’s literally in the language.”

“The law’s very clear. You can apply for asylum irrespective of how you come into the United States. It’s literally in the language.”

That means people who cross the border in the desert have the same right to apply for asylum as people who try to apply at official border crossings. That’s an important point to start with, because it doesn’t fit the typical Trump administration rhetoric around asylum.

For example, recently-departed Attorney General Jeff Sessions, in defending his Zero Tolerance policy earlier this summer, said, “The border is not open. Don’t come unlawfully. Make your claim, make your application and wait your turn.”

Again, the law says it doesn’t matter how asylum seekers enter the US. But, for the sake of argument, let’s say you want to stay on the good side of people like Jeff Sessions. You don’t want to cross the border in the desert. You go to an official border crossing, what’s known as a Port of Entry – like San Ysidro at the Tijuana-San Diego border. The agency you deal with is Customs and Border Protection, or CBP.

“Because the way the asylum process begins at the border,” says Hing, “is that once you’ve stated something such as, I’m here because I want to apply for asylum, that’s very clear, or I’m here because I’m afraid of the violence back in my home country, once you say those words the border patrol… are obligated to interview you for a credible fear interview. And if you pass the credible fear interview, then you get to apply for asylum in front of an immigration judge.”

The 1980 law defines a refugee as a person who has left their country and can’t return “because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.”

The 1980 law defines a refugee as a person who has left their country and can’t return “because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.”

If you are among the over 60% of asylum seekers who lose, you get deported back to the country you left. But win your case, and you walk out a free person.

That’s a very simplified version of a complex process, but it gives you an idea of how things are supposed to work. However, a lot of asylum seekers can’t even get started.

“When the complaint is that these individuals should follow some legal process, they are trying to follow a legal process,” says Hing.

That can be harder than it sounds.

We have very credible information that the border patrol is lying to people at the non-Ports of Entry,” says Hing. “We’ve heard reports of them telling people go away or if you don’t go away you’re going to go to jail, come back another day. Some of them have been told to go to the Port of Entry, but there’s all kinds of shouting and coercing people who have come over the border to go back across the border.”

Human Rights Watch obtained a recording of asylum seekers being turned away at San Ysidro Port of Entry in February 2017.

“The border patrol,” Hing continues, “is definitely violating US immigration laws and international conventions on how to treat refugees.”

“The border patrol … is definitely violating US immigration laws and international conventions on how to treat refugees.”

Customs and Border Protection is currently being sued over this. An immigrant legal aid organization, Al Otro Lado, claims they’re creating dangerous conditions for refugees by making them wait at border crossings where they’re easy prey for drug cartels and gangs. The suit says CBP agents have threatened to deport asylum seekers and take away their children, that sometimes they use force to physically move asylum seekers out of ports of entry and that they’ve coerced asylum seekers to recant their fears on video.

CBP declined to comment on the litigation, but sent a statement that reads in part: “CBP processes undocumented persons as expeditiously as possible without negating the agency’s overall mission, or compromising the safety of individuals within our custody.” It goes on to say “individuals presenting without documents may need to wait in Mexico as CBP officers work to process those already within our facilities.” According to the agency, San Ysidro can only accommodate 100 asylum seekers under ideal conditions with current staffing. But an Amnesty International report concluded “the supposedly unmanageable number of asylum claims appears to be a fiction.”

So let’s look at how you get to be one of that very limited number of asylum seekers who gets processed.

It’s 7:15 in the morning at the San Ysidro border crossing. Andrew Free is an immigration lawyer and volunteer with Al Otro Lado, the migrant aid group that’s suing CBP.

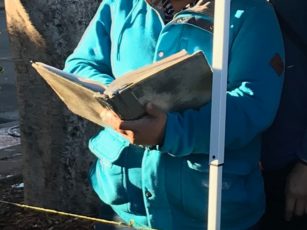

“That’s the list right there, you see the tracks those two?” he says, “like you would get in the line for the movie. That’s where you go and sign your name up.”

Free points to two parallel lines of tape on the ground. The list is a notebook complete with duct tape down the spine. It is the gateway to the asylum process here. You get in line to get your name written down on the list, and then you get a number. But the numbers aren’t posted anywhere; you just have to make sure you’re back when your number is called.

Amanda McArthur is another legal volunteer with Al Otro Lado. She explains, “the way the list works is each day the US CBP calls up Mexican immigration and tells them how many people they are going to take in the morning in the afternoon. It can be anywhere from zero to a hundred people for the entire day.”

Every day, a crowd gathers when it’s time for the numbers to be announced. A man holds up the notebook and calls out a number. There are ten people listed for each number. But there were nowhere near that many who came up when I was watching.

Al Otro Lado is part of a lawsuit challenging the legality of this system.

“This list is intended and in fact circumvents the processing of that person by creating this barrier for thousands of people,” says legal volunteer Andrew Free. “They have it in a notebook. You know, like there’s no process, there’s no real process for challenging, for notice. Nobody knows what the number is today at the shelters. Nobody knows exactly how fast it’s going to move or how many people will be available to go in per day. Nobody knows what happens if you miss your number by a day because you had an emergency with your child. And it’s because it’s made up.”

But one thing the list does do: it creates hope, especially for people who can plead special circumstances.

Andrew and Amanda and I are here at the border crossing to meet someone who fits that description. Sara (not her real name) is 78 years old and from Venezuela.

Today’s the day she’ll try to apply for asylum at the official crossing.

“My daughters live here in the United States,” says Sara. “And that’s all I have. I don’t have anyone else. In Venezuela, I’m alone.”

“My daughters live here in the United States. And that’s all I have. I don’t have anyone else. In Venezuela, I’m alone.”

You could hardly invent a stronger case. Sara’s fleeing Venezuela, a country the US government frequently accuses of human rights abuses.

“I’m here because I need to request political asylum,” says Sara, “because I’m persecuted, by the military, by President Maduro, and they’ve even tried to kill me.”

Sara is elderly and in poor health.

“I suffer from rheumatoid arthritis, bone problems,” she says. “I almost can’t walk. And I have hypertension. I suffer from low blood sugar. I’m very sick. It’s not possible to get treatment in Venezuela, because there’s no medicines. And I had a heart attack.”

That makes it almost impossible for her to show up at the border every day hoping her number gets called.

But there is a way around the wait. See, the list isn’t actually directly managed by US or Mexican officials. It’s managed by other migrants, volunteers, who are basically liaisons.

“Each day the people who are in charge of the list,” says legal volunteer Amanda McArthur, “I believe there’s about four or five of them, talk with each other and decide who needs to be put forward because they’re very vulnerable.”

The list volunteers agree that Sara’s case should go to the top, and she is all set to cross the border.

Of course, that just got Sara to the border. What happened next is hard to tell. McArthur hadn’t heard from Sara for days and didn’t know where she was in the system. Basically, the day Sara got through The List, it’s like she walked into a room with no windows. And people outside can only guess at what’s happening.

When asylum seekers wait for their credible fear interviews or immigration hearings, they’re often held in short-term detention facilities known as hieleras, or freezers. A federal judge called conditions at one “deplorable.”

Al Otro Lado is using Sara’s case to make an argument: that the US has made applying for asylum at official border crossings so difficult that people who fear for their lives are forced to try more dangerous ways to cross.

To get even get started in the asylum claim system, Sara needed a team of legal volunteers. They had to know to go through the list, instead of straight to the border. To avoid a wait of weeks or months, they had to convince another group of volunteers that Sara needed to be sent straight through. And after all that, she still basically disappeared for a few days.

So Al Otro Lado is trying a new strategy: getting members of Congress to accompany asylum seekers who try to cross at Ports of Entry. They want the people who make the laws to see how they are being carried out – or not.

“Every person should be calling their congresspeople within the United States, California and say … this is a call to action,” says McArthur. “We need to have changes in the way in which people are getting access to asylum.”

“Every person should be calling their congresspeople within the United States, California and say … this is a call to action. We need to have changes in the way in which people are getting access to asylum.”

Last Friday, the Department of Homeland Security made a Facebook posting about the death of Jakelin Caal Maquin, a 7-year old Guatemalan girl who died in CBP custody after crossing in the desert. Part of it read: “Please, we are begging you, present yourselves and your children at a port of entry and seek to enter legally and safely.

For some migrants stuck outside San Ysidro for weeks on end, that may not actually sound safer than crossing in the desert.

As for Sara: Just before we went to air, Amanda sent me an update. Now they know where she’s at. But Amanda still doesn’t know whether she’s passed her credible fear interview, whether she’s still waiting for it, or really – what’s next.

________

Lucy Kang is a reporter with KPFA.