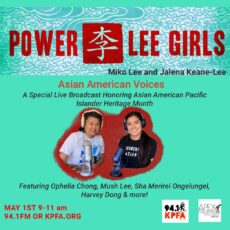

On May 1 from 9-11am The Sunday Show celebrated the first day of Asian Pacific American Heritage month by turning the reins over to Apex Express. Hosts, the Powerleegirls Miko Lee and Jalena Keane-Lee live broadcasted a series of conversations with some of the AAPI movers and shakers in the Bay and Beyond. Check it out:

On May 1 from 9-11am The Sunday Show celebrated the first day of Asian Pacific American Heritage month by turning the reins over to Apex Express. Hosts, the Powerleegirls Miko Lee and Jalena Keane-Lee live broadcasted a series of conversations with some of the AAPI movers and shakers in the Bay and Beyond. Check it out:

TRANSCRIPTS: AAPI Heritage Special – Asian American Voices

[00:00:00] Open: APEX express, Asian Pacific expression and unity and cultural coverage, music, and calendar coming to you with an Asian Pacific Islander point of view. It’s time to get on board – The APEX express.

[00:00:34] Miko Lee: Good morning. You all happy Asian American heritage month. We want to thank KPFA for the opportunities to broadcast this show on Sunday during this 9:00 AM slot. Thank you Philip Maldari for giving up this day and time for us to celebrate AAPI heritage month. He’ll be back next week to bring you another Sunday show.

[00:00:56] Jalena Keane-Lee: Today you get to hear from the Powerleegirls of APEX express, I’m Jalena

[00:01:00] Miko Lee: and I’m Miko.

[00:01:01] Jalena Keane-Lee: We’re a mother daughter team. And today we’re honoring the first day of AAPI heritage month may was chosen to commemorate the immigration of the first Japanese to that, to the United States on May 7th, 1843. And to mark the anniversary of the completion of the transcontinental railroad on May 10th, 1869, the majority of workers who laid the tracks were Chinese. We are descendants of those railroad workers throughout this month, you’ll be hearing shorts from our series. We are the leaders. This is an ode to one of our heroes, Grace Lee Boggs quote. “We are the leaders we’ve been waiting for” our shorts, focus on AAPI activists of the past and present. So keep your ears open for those spots. Throughout this month. Today, we’re going to take you on a journey with a series of conversations, with a few of the AAPI, movers and shakers that we admire.

[00:01:48] Miko Lee: We start off our special with a poet storyteller, educator and advocate. Michelle Mush Lee. Mush is a story boss who is graced so many stages around the nation. She uses poetry to enact culture change. Mush has been featured on HBO, PBS Afropop and so many other places. Welcome Mush to APEX.

[00:02:12] Mush Lee: Good morning. Thank you so much for having me.

[00:02:14] Miko Lee: We’re so glad that you could join us. Can you just start first by talking to us about the importance of storytelling, especially within the context of Asian American Pacific Islander heritage month.

[00:02:28] Mush Lee: Yeah, I want to wish everybody a happy AAPI heritage month history month and also API futures month. I have been a storyteller for most of my life, but I often credit my grandfather as the person who seeded my love for oral poetry of public speaking and storytelling. And it started in his church pews. He’s a pastor, a Presbyterian pastor, and I spent a lot of time listening to him, command a room and tell stories of justice that were found in the Bible. And while that’s not my profession, I, I don’t command religious basis. I did find my love of voice and of speaking truth to power from him.

And, one of the simplest ways to describe why I think stories are so powerful is that there’ve been so many stories that have been written about us without. And the importance of being able to share authentically who I am, who has made me the person I am. And with all my complexities is something that I think is under hurt. And so I’m always honored when I get to share my poems. When I get to talk about my life and my journey into a leader and as somebody who just loves and understands the power of stories to change the way that we see ourselves in each other.

[00:03:47] Miko Lee: Thanks, Mush. I love that we have so many commonalities. One is I have a dad that was a preacher too. And so I get that preach into the world. And also my legal name is Michelle Lee.

[00:03:59] Mush Lee: So is mine. There are 12 million.

[00:04:02] Miko Lee: Yes, exactly. Miko is my middle name, but I think there’s Michelle is like that grace name for Asian folks for some reason.

[00:04:09] Mush Lee: Every time I go and I sign up for a gym membership or a coffee reward programs are always like, which Michelle Lee are you.

[00:04:16] Miko Lee: I know it’s so funny. You, it is so funny. Talk to me a little bit about your journey. You won congratulations as an order because you’ve just stepped in as the executive director of youth speaks one of the premier poetry slamming places in the country, and you started out there really young as a student. Or as a student teacher, right? Talk to me about your journey.

[00:04:41] Mush Lee: I am almost 40. Now I’ll be turning 40 this month, but it was about 19 years ago that I first stepped into a youth speaks program. So there’s a program that still exists. Believe it or not use speaks has been around for 25 years, started in San Francisco in the mission district. We work with young people to develop an amplify and apply their voices. However they so choose whether it’s poetry, whether it’s through policy, whether it’s through business. But the idea is that understanding the power of your voice and being able to share that powerfully authentically is really the core of what we do.

There’s a program called the under 21 open mic. I had just turned 20. So I was like a month, maybe even three weeks into my twenties. And I said I was studying abroad in college. The war had just broken out. This was 2003. I was just reading so much about the dissenting kind of. Protest movements that had sparked up many that involved and were led by artists across the country. When I came back, I was just fired up. I wrote terrible poems about how we needed to change the patriarchy about how, I was a college student too, and how we needed to change white supremacy. And I brought my first poem to an under 21 open mic on Folsom street in San Francisco. You speak still host this program.

And I got on the mic and I did the som I was like raged. I was passionate. I was nervous. And at the end of the open mic, the founding executive director, James cabinet, oh my God. We do programs like this. You should come to an afterschool workshop or you should join our youth advisory board. And I was. Offended. Cause I, in my mind I’m a grown adult. I’m I’m about to graduate college, sir. And he quickly learned, oh my God. Okay. Do you want to come and interview for a staff position? So that’s how I got my starting youth speaks. My first teaching gig was in east Palo Alto. So at Belle Haven middle school. And that’s, I just I never looked back.

[00:06:38] Miko Lee: Oh, I love that you were offended. He thought he was doing an honor by saying, Hey, join this. And you were like, wait, what dude?

[00:06:44] Mush Lee: I’m the first to graduate college, also proud of myself and feeling like I’m a grown person, I’m going to have a salary. This was before I knew what it was to have a non-profit salary. We’re changing that slowly but surely. But yeah, that was my first introduction to you speaks.

[00:06:58] Miko Lee: Okay. So you started out as this young person that was performing and then you became a teacher at youth speak. So is that.

[00:07:05] Mush Lee: Yup. Yup. And I, I would drive around to public schools all across the barrier. I’ve probably been to every single public school and a handful of private schools. And I would just drive myself and ask a bunch of poets that were my age that, loved this idea of using our voice, using culture, the oral tradition, hip hop, kind of aesthetics and ethos, those values that drive us like love continuum speaking truth to power justice, all of that. And we would perform, we started performing in cafeterias, in schools, across the bay. And from there, I just, I really. How many voices, young people’s voices were just ignited by seeing and hearing somebody that looked like them that were speaking in a way that sounded and felt like them. And since then, I, I moved through the organization was a teaching artist served as a program director left to get my masters came back and did some field building work with other organizations, eight organizations across the state of California. At that point I was, maybe had been 12 years. There. And I decided, okay, I’m going to start a family. I’m going to see what the world looks like outside of this organization that I love spent five years working in city, government, running my own consulting business. And then the opportunity to step into this role opened up and I thought long and hard about it. And it’s so crazy. But here I am, again, almost 20 years later, I love that coming home in a way.

[00:08:33] Miko Lee: And you stepped into this position during these pandemics, both the COVID-19 and then during the racial uprisings, how has that impacted your work?

[00:08:43] Mush Lee: There’s one statistic that I still it’s. It doesn’t shock me, but it does. It leaves an impression on everyone I share it with. So I’ll share it here, which is that in the nonprofit sector across all kind of focus areas, less than 3% of the executive director positions are held by AAPI leaders. Are women of Asian-American descent. And it, before I stepped into this role, a lot of my work here in the city of Oakland, both as a cultural affairs commissioner, but as it just as an artist, as a poet and as an activist was to notice that the narratives that were being told were very similar, very early on, right after George Lloyd’s murder shortly after Brianna Taylor’s murder. There were a lot of the same stories. I remember from the early nineties. Now I was in sixth grade in 1992 and the LA uprisings were happening and it impacted Korean business owners immigrant communities outside of the AAPI community and a lot of black communities down in LA. And I remember the narrative being so slanted and skewed through the media about how it was a race war, particularly between AAPI and black communities.

And as I did more research and studied, and I realized that what was also happening. That wasn’t being uplifted or stories of solidarity and of understanding that many of our communities of color had actually been subject to the same systems of oppression and injustice and racism, and that weren’t being told. And so this time around it was incredibly important for me now. I’m, I’m in my almost forties, not 12 years old anymore. It was so critical to me to share and do everything that I could to organize it, both API leaders, but also allies to make sure that we’re uplifting and advancing the stories of solidarity cross-culturally.

And so that was a lot of my work right after the George Floyd martyrs and the uprisings that happened. And so when I stepped into this role, it was imperative to me that was something that was being named and that we were doing everything that we can to also share space for young people to explore, not just stories of oppression, which are. Especially when you’re developing kind of your understanding of the world, but also that there are so many stories of resilience. So many stories of sharing our understanding and our analysis of power and how to work together to create coalitions to great power, to create a just world. Thank you for that.

[00:11:19] Miko Lee: So much of what you said resonates with me. One, just from the very beginning about being a woman of color, an Asian American woman of color in an arts, nonprofit, I’ve been there. I’ve done that. I, that feeling of folks, when you’re the leader of an organization and you step in the room, but the other folks, the white folks look at your staff member as if they’re the leader, instead of you. That happened to me many times. So those kinds of feelings I totally relate to. And then this issue around stereotypes around Asian-American folks, the lack of solidarity, and also the kind of silent part that some of the stuff that Juliana and I tried to do on the show is one to talk about solidarity work, and also the Asian-American activist heroes. There are so many of them. So thank you for lifting that up. I’m wondering if that is connected to the whole ethos, that youth speaks around people, pedagogy and purpose.

[00:12:14] Mush Lee: Yeah. I’ll start with the word that, folks are may or may not be familiar with, which is pedagogy. It’s a fancy kind of multi-syllabic words. That just means the art and science of teaching. And there’s one kind of, there’s one concept. That’s always driven our work and our engagement with young people. Since, I was there almost 20 years ago, which is this idea that we move both from the oral, from the. Oh, R a L. So whereabouts, public speaking, we’re about truth to power. We’re about, sharing your stories publicly once you’re at that point where you feel comfortable, but it goes from the mouth to the ear, the oral, but a U R a L. So it’s this idea that the speaker is just important as the listener and the listeners just as important as a speaker. And it’s actually this kind of conversation. So there is this premium on being able to listen actively and compassionately. And I think that’s something that is desperately needed right now is the skill and the space to exercise both of those at the same time. And I think that is essential to movement work.

[00:13:23] Miko Lee: Yeah, absolutely. I’m wondering what is a piece of your AAPI ancestral knowledge that you want to share during this month?

[00:13:32] Mush Lee: Thinking about this question, it’s such a beautiful question and there’s two things. One is one is one, is this it’s I don’t know if it’s ancestral knowledge. Oh, I think it is. It’s the fact that, I’m of Korean descent and the story about our people in our country and how we have survived across generations. That was hidden from me or just not shared was this idea that we are, we have never invaded, or we have never been on the offensive when it comes to survival, meaning we’ve always been attack across history and generation and we have never an acted war, but we somehow managed to survive. And keep our culture and our people intact.

And there’s something incredibly heartbreaking about that. And there’s something also really powerful about that. And I think the piece of ancestral knowledge is that we are a people of survival and it’s so easy, especially with all of the stereotypes that exist in the fitness world about what it means to be Asian and American.

There’s so many kinds of negative disempowering tropes. But that’s something that I wish for my son and all young girls who look like me to understand that we are both descendants of revolution and revolutionaries and that we that violence and this central idea that we can, we should survive off of violence and power and balance is something that’s just. We as a people have debunked over time. So that’s something that’s important.

[00:15:11] Miko Lee: Has there been a particular poem that you’ve written that you’ve participated in that was really an epiphany for you that you felt like, oh, this is the one that I’m transforming the way I’m thinking about the world or a poem that you’ve heard from somebody else.

[00:15:26] Mush Lee: Oh, I love that question. I, I say this often, and I think this might be true for other writers as well, which is that I think I’m always writing the same three poems again and again. So the first poem I ever wrote is probably the same one. I’m still rewriting and editing now. And they’re, the themes are, I’m always writing about my mother in some way. One of the first poems that I ever wrote that received a lot of, kind of attention and love and a lot of people coming up and saying, oh, that was, I still feel, that was a poem that was called I’m a little embarrassed to share it because it’s such a mean title, but it was not my mother’s. And there’s it. There’s a lot of, resonance with, mother-daughter relationships with folks, that we’re experiencing tough relationships and I love my mother and we’ve also had she grew up without a mother. So in many ways she was creating her own blueprint for how to become a mother.

And I didn’t know that, and there was a lot of tension and a lot of ambiguity around why she made the decision she made as a mother, as a parent, as a woman. And so I think that was one of the first kind of life-changing poems to be able to assess, figure out why I was so angry. And then the poem that proceeded that, which then became like, Blessings, they were they’re called benedictions and the church, which is what the pastor gives at the end of the service at the end of the liturgy, when their blessing, their blessing, everyone that’s come together to, have a good week and to receive the love and just to go out and become, agents of love and that, and I think that probably was the most profound transition as a writer and in my life as a woman and as a mother and as an artist, which is a transition from holding onto the rage and speaking only at the rage and being able to transform into really stepping inside the story that my mother lived, the best that I could using my imagination and really talking to her about her life and then being able to move into a place of, what king called redeeming love and mercy. And since then my poems, I struggled really hard to write poems about love. It just didn’t come naturally when I was young and angsty and just fired up and everything just didn’t make sense to me, everything seems wrong. And now there’s a, there’s finally some balance and equilibrium that I’m finding in my artistic voice that I hope to carry through the rest of my life.

[00:17:46] Miko Lee: That’s so beautiful. Thank you so much Mush Lee for joining us on this AAPI special. Next up, we are going to get a chance to listen to Moshe’s poem, dreaming America. Listen to Misha’s poem, Dreaming America.

[00:18:20] Mush Lee: Been keenly suited to this sacred task of threading justice, to joy stories, to solidarity, persistence, to power in our pursuit of freedom and the pursuit of. Never been fought ourselves or alone, but we’ve always done this together. Like you have Ang Lee and our flowers,

see Willie dream with dream a new America. We carried the courage that once belong to the giants whose shoulders we stand on today, you don’t choose the column suit, but you do choose who you want to be. Wong Kim Ark and Frederick Douglas, a restaurant burger and abolitionists who helped make the path to citizenship possible for my grandparents and me,

he dreamed of a path to citizenship so we can actively participate in our American. When we dream we’ve remembered the deep tradition of movement workers coming together across dividing lines to create a cultural response to racism. That’s rooted in power healing and solidarity. This is where dreams come from radical self love and love for community from stirrings like Bayard and striking like and wit and Chavez and Vera Cruz from holding the humor and heartbreaks of this.

And still waking up each morning with the humility of wonder from radical self-love and radical friendships like URI and Malcolm brace and Jimmy, Bruce, and Jesse, every dream or notes that when we add ourselves to the collective, we are forever connected.

[00:20:08] Jalena Keane-Lee: That was dreaming American by mostly next up, we talked to Shaw, Mary Ray, the Palauan American climate justice activists, digital strategists, artists, and creator of the being Micronesian hashtag. Hi Shaw. Thank you so much for joining us.

[00:20:24] Sha Ongelungel: Good morning. Thank you for having me happy may a happy Asian-American Pacific Islander heritage month.

[00:20:31] Jalena Keane-Lee: And thank you for being here. I was wondering what are some of your intentions for this month?

[00:20:39] Sha Ongelungel: It’s the same every may. And sometimes it comes off abrasive to people, but always reminding people that the PAI in AAPI isn’t violent and also reminding people that Asian American, just Asia in general is a much larger population span of land than a lot of people realize. And that’s just, that’s been what I’ve been talking about every may for, a years now.

[00:21:11] Jalena Keane-Lee: And thank you for doing that. I want to talk a little bit about reclaiming narratives and how important that is specifically in your climate activism. Could you talk a little bit about, owning your own narrative and being able to tell your own story?

[00:21:24] Sha Ongelungel: Yes, actually, I am executive director of a nonprofit called the Pacific uprising. And our mission statement is telling our own stories on our own terms and a big part of it. And this is in climate justice, but also across a lot of movements bases. And the media in general Pacific Islanders are they’re an anomalous group out of a very large classification, AAPI as a very broad term. And a lot of people don’t know or realize that Pacific Islanders are a very diverse group. And especially in climate justice, a lot of people don’t realize how long Pacific Islanders have been in that space and the kinds of work they’ve been doing for the amount of time they’ve been doing it. And also because it’s population of people who have been facing some of the harshest consequences of the climate crisis while contributing beliefs to it. And so part of my work has always been making sure that people recognize that.

[00:22:30] Jalena Keane-Lee: Can you talk a little bit about some of the climate justice projects you’re working on right now?

[00:22:33] Sha Ongelungel: It’s across the board. I don’t specifically just uplift Pacific work because climate justice pertains to so many different things and because at least in the way I look at it, everything is interconnected. But my focus has always been on the frontline, particularly indigenous black and other marginalized groups and uplifting and amplifying those voices in the climate justice space.

[00:23:01] Jalena Keane-Lee: Thank you so much for doing that. It’s so necessary and timely as we all know, and in the climate justice space, I think there can be a lot of despair. And I’m curious what kind of helps to keep you hopeful in fighting to protect our planet and the environment?

[00:23:17] Sha Ongelungel: My mentor, one of my closest friends we’ve talked about this a lot and when you’re from a community that’s adult with a lot of trauma, intergenerational trauma, and continuously acquire throughout our lives trauma, you have a dark humor, dark sense of humor about things. And so we say that our foundational principle is ridiculousness. And just looking for that. Free entertainment out of everything that we’re doing all the time, however, small it may be, which I mean it’s definitely rooted in some dark humor, but that is oftentimes just how people cope.

[00:23:57] Jalena Keane-Lee: And what are some of the other kind of guiding principles that help shape your work?

[00:24:01] Sha Ongelungel: So my father was an activist in the 1980s. He was actually fighting against us militarization and imperialism in the Pacific. And one of the things he taught me and I think this goes back to what I was maybe four or five years old. So this has been just very fundamental for me. Is that any decolonization work that you do, if it is only for your own community, it is not the, or. They call them position work means that you are uplifting and amplifying messages for your fellow indigenous people, your fellow, marginalized people. Because if you’re not doing that, you’re not recognizing the interconnectedness of things. And if you’re not recognizing that, then you’re not fully doing decolonization work.

At the same time, if you’re doing the conization work and not doing not indigenizing, as you’re doing it, then you’re only doing half the job because you can remove all of those oppressing factors and the people and everything. But if you, as a community are not working on indigenizing, then you’ve done the work of fighting against something. But what have you fought for? What are you building? That’s not still rooted in those. Colonial mentalities and principles and white ideals and methodologies. And then, yeah, that’s, those are some pretty basic things that are in my personal activism, my professional life, my personal life, all of it.

[00:25:41] Jalena Keane-Lee: Thank you for sharing. I agree and feel like it’s so important to think about, not just what are we trying to tear down or take down, but also what are we creating and how to do that and what principles we want to have in that. You mentioned your dad and I know he was also an artist and artists and activists, and you’re an artist as well. So I’m curious how art plays a role in your life and in your work?

[00:26:07] Sha Ongelungel: It’s I guess it is also a foundational thing for me. Because. Pants are qualified migrants there in the United States because of the compacts of free association between the Republic of plow and the United States. My dad talked a lot about messaging and narrative and talking to people without necessarily speaking the same language. And so he taught me that through art, whether it was visual art or sound design, just different ways to express yourself that didn’t necessarily require language. And so I look at that even in the production and creation work that I do within climate justice and all my personal activism.

[00:26:55] Jalena Keane-Lee: And it’s such a special experience to, to grow up with an artist activist parent. My mom is also an artist activist and we do this radio show together. But for so many of, my friends and just people that I’ve met throughout life, they have not had that experience. And haven’t had that kind of relationship with their parent. So I’m curious if you have any advice or words of wisdom to people that are maybe coming to activism later in life or don’t have that kind of family support and that foundation growing up

[00:27:26] Sha Ongelungel: the internet is a very useful tool. I started building digital community. Gosh, it goes up probably as far back as 1996, but. If it’s what you’re passionate about. If that’s where your heart is, if that’s the work you really want to be doing, whether or not you have the support tools on the internet, we’ll connect you with people, they will teach you things. There’s, especially in the United States, there’s so many ways and that you can connect with people online and there’s so much information that’s free and accessible. That it’s a great starting place. And it’s a great tool to use.

[00:28:07] Jalena Keane-Lee: And speaking of social media and building community online, as, as you spoke to it can be such a beautiful way to build community, but of course we know that it can also be rather hostile and challenging, especially for women of color. So what has been your experience with creating boundaries with social media and yeah, just boundaries for your mental health and your active.

[00:28:27] Sha Ongelungel: It’s definitely a been a journey. I, early on, I would say probably in my early to mid twenties, I had a really hard time with it. There was definitely no separation and no boundaries. Today I can say that there is a lot of non-separation only because for me, that’s still, I don’t want to fragment myself, but in terms of boundaries, it’s just, if I feel tired, I’m logging off. If I’m not happy with it right now, I’m logging off. If things have me stressed out, burned out, I’m just, I’m logging off. I don’t feel the pressing need to react to everything right now as it’s happening. I just. The constant need to always react and always be on top of things. I’ve experienced that so much professionally that I just don’t do that personally anymore. And in practicing that in my personal life, it just spread into my professional life and I’m just, I don’t want to rush and react and have knee jerk reactions. And if it doesn’t feel right, I’m not, or it, and it feels like embracing that is part of decolonization work of, letting go of that scarcity mentality and the feeling like we have to always, react right away or do things on someone else’s timeline.

[00:29:54] Jalena Keane-Lee: I saw that you were also named miss LGBTQ by the plow humanities project. And so I wanted to talk about queerness and how queerness impacts your art and activism.

[00:30:08] Sha Ongelungel: It’s funny because I, wow. That was ages ago too. So that happened shortly. I want to say shortly after I left the Republic of flaw, which was the whole entire time I was living in working in pullout from the end of 2011 to the roughly the end of 2014 homosexuality was criminalized. They actually decriminalized it a month after I had left. And so a lot of the things that I experienced while I was living, there were not so pleasant and crossed over from like my personal life into my professional life. And there were a few moments of violence from within my own family and it was rough, but my parents have been the kind of people who like they’ll defend me when I’m not there.

My mom did a whole Facebook post and some Palauan Facebook group, I think like in 2012 where she defended me and it kinda looked like my mom outed me in a Facebook group, which, I wasn’t in a hiding. It was just very my mother was like, this is my child. She is queer. This is, I accept her. And I was great. And I’ve been fortunate enough that I don’t have to worry about it. I have really, I have a really open relationship with my father, especially. And so when I talked to him about everything from like queerness to how I participate in the kink community, I can talk to my dad about these things. And it’s just, it’s not an awkward or unusual or uncomfortable thing for me. It’s just very this is what I’m thinking about. These are the things that I’ve been doing. I just want you to know, I want you to know I’m safe and it’s fine. I just. I’ve been very fortunate in that time.

[00:31:57] Jalena Keane-Lee: Oh, that’s great. And we’re asking all of our guests today, what is a piece of your AAPI ancestral knowledge that you would want to share?

[00:32:10] Sha Ongelungel: I don’t think that it’s specifically a piece of Palauan ancestral knowledge. This is something that’s an indigenous concepts across the board. And it’s something that I speak about throughout the year and that’s that genuine solidarity can not be rooted in transactional relationships. That’s how colonization happened. It’s my obligation as an indigenous person indigenous to the Pacific. And it’s how I honor my ancestors by. Practicing and showing solidarity by just building relationships with people, by caring about people. A lot of people now talk about how mutual aid is this very revolutionary concept.

And it’s not because for a lot of people, it’s just culture. And so when we talk about solidarity, it’s, I’m not doing something for someone or someone is doing something for me because we necessarily get something out of it. It’s just, that’s what you do. That’s how you care about people and you do what’s best for them. And they do what’s best for you and you take care of each other and that solidarity and anything else is basically mistaking proximity for power as indigenous people to Pacifica. When I look at our community, we are. Proximity to power is just us falling into the colonial mentalities. And it’s not necessarily specific to my community, but this is an indigenous concept across the board.

[00:33:50] Jalena Keane-Lee: Thank you so much for sharing that with us and thank you so much for joining us today. Next up, we’re going to hear Shaw’s song for sore. You.

[00:35:55] Miko Lee: That was our guest Shaw, Mary Ray. Song for saw you. We are so pleased to welcome playwright, Sam chance. Who’s the author of many plays, including trigger what you are now. The opportunities of extinction, fruiting bodies, the other instinct Lydia’s funeral video about that whole dying thing and Asian American Jesus. Welcome Sam chance. Hey good. How are you doing?

[00:36:21] Sam Chanse: I’m all right. Thanks.

[00:36:23] Miko Lee: You have a play. That’s going to get its world premiere pretty soon at the magic theater and it’s called monument or four sisters a slothy play. Can you tell us first, tell us about the title and where this play comes from?

[00:36:39] Sam Chanse: Yeah, it’s a mouthful. So the title it’s monument or four sisters and the slot play is in parentheses. And in some ways there’s these two plays happening. It’s there’s four sisters who are at the center of the story of the play, and there’s a, been a disruption in their community of sisters. One of them is missing in a way, and they’re searching for her, trying to see if they can get her back. And they’re also at the same time grappling with these private catastrophes in their own lives and reckoning with larger global catastrophe. And at the same time, the play has these anthropomorphized cartoon slots that we’re following going on this adventure. And they are they’re somewhat tied to one of the sisters who writes for a animated kids’ show, but we’re following these slots who are also reckoning with a kind of catastrophe. And I think, fuzzy floods are good to do that with. So that’s why I wanted the title has that in breath as he is to bring the whole piece because all of those things are happening. And I think it’s important to in the title. Monument is very, there’s a heaviness to it. It is about questions of legacy and monument, but there’s also a real there’s laughter and play that’s involved. The title reflects that. And that’s part of why it’s there, because I think that sense of laughter and play is vital to reckoning with these really big painful questions.

[00:38:05] Miko Lee: Oh, wow. So it’s a play within a play kind of sounds fun. Of course it hasn’t opened yet, so I haven’t seen it. I’m looking forward to seeing it. So I want to know more like it’s about four sisters. Do you have sisters?

[00:38:19] Sam Chanse: I do have sisters and I have, I am one of four sisters, and this is not the first play I’ve written with sisters. I, in fact I think I write about sisters a lot, like two sisters or three sisters or brother and a sister. But I think this is the first time I wrote about four and I had to be very careful with my sisters, letting them know this is not about us. It’s just, I’ve really, I had such a desire to write about because it’s such a big part of my identity growing up. And so I think I had this idea of making a play about four sisters for a while. And also because the play is looking at these questions of a lot of catastrophe and again, in private, intimate ways and also global ways for in Chinese it’s Amanda is is death. Like I think when I was I’m the fourth kid and when I was growing up, I was always reminded that there was a very unlucky number and it was death. So that number also felt appropriate for just a little light thing to grow up with hearing about all the time. Oh yeah. Totally. It really makes me feel like you’re blessed.

[00:39:23] Miko Lee: Yes, absolutely. I was, we were talking earlier with Mush Lee the poet and she was saying that she tells, yes, I love this. And she was saying that she tells the same or rewrite the same three themes in poems all the time. And I’m wondering if that’s something, as you talk about your sisters and writing about them, if you feel there’s kind of themes that you write about again and again.

[00:39:48] Sam Chanse: Yeah. I love that much that night. I do. Absolutely. I think I returned a lot to the sisters and also I think I returned a lot to questions of belonging and community and. W this, this plays a lot about other said there’s been a rupture and an absence. There’s an absence in the community. And there’s also one sister reckoning was feeling that she has lost her community, not only the sister community, but a larger sense of that. And trying to find that sense of belonging. Again, I think I returned to that quite a lot. And a lot of this one is like, how can we become whole, can we become, come back from loss and come back from catastrophe and find a sense of self and a sense of wholeness again. And I think let’s see. I think my, I also, I’m always writing Asian American issues. Like there, it’s not always as explicit. It’s built, it’s baked into the perspective of the characters often. And so that’s threaded through a lot through all the plays in a lot of ways. But those are the ones that first come to me.

[00:40:48] Miko Lee: And when, what did you actually start writing on the monument play? D were you working on that during this last two years of the lockdown?

[00:40:58] Sam Chanse: No. No, I actually started it in the very final weeks of 2017. And I remember cause it was about almost a year. It was a little over a year after the 2016 election. And there was this, it had been a pretty brutal horrifying year and I felt like the pressure had been mounting for so long before I actually started writing the play. And then it that’s. So that’s when I started. And now of course we’ve had a lot of brutal, horrifying years and including the pandemic, but the play was. It was before this all started with dependent. Now, and unfortunately still pretty brutal, horrifying, but I D I’ve been doing some rewrites since, but the play itself was written before.

[00:41:37] Miko Lee: Oh, that’s interesting. But it will have resonense given the times that we’re living in. That’s fascinating. How has the rise, are you living? Wait, let me just ask, are you living both in New York and California at this point? Or where are you based?

[00:41:51] Sam Chanse: So right now I am based in California and in Los Angeles, but that was re that’s pretty recent. It was only the summer. So I was in Brooklyn up until July last year. So now I’m actually right now, I’m in New York because my family is having a little bit of a medical situation. So I’m here to be with family, but I am based there. And I was in New York since about 2009, but, going or moving around a little.

[00:42:16] Miko Lee: And I know you have a lot of bay area ties that you have, your show is opening at the magic, but you have a long history of being at the bay area, including being the lead of Kearny street workshop for years. I’m wondering what it feels like to come back to the

[00:42:29] Sam Chanse: it’s just you at the anniversary. I oh my God. It’s yeah, no, I, the bay area is such a artistic and everything like soul home for me and coming back is really meaningful. I was. So when the magic reached out about doing this play, which was like right before the pandemic and the around February, 2020, I was so grateful to have the chance to come back and work in the bay again, because I was there for almost a decade, working with Kearny street, working with with spindle, surf and locus at the time. And it’s so formative for me as an artist like it’s still all those organizations still continue to be homes and nourish and energy. Asian-American writers and artists of all kinds. And that was, it was such a, it’s such a, it’s a place it’s so important to me. And I feel very grateful to be returning to it after so long.

[00:43:20] Miko Lee: And now you have a lot of work that’s happening in New York to you. You’re, you’ve just done shows in the fast past few months with public theater and ensemble, studio theater. What’s next for you? What’s your next show? Where is it going to be?

[00:43:34] Sam Chanse: Yeah the next one I’m going to be doing is as a show at the university of Rochester in the fall cat Yannis directing, and it’s called fellowship. So that’s the next new play I’m working on. And and then I’m also working on a musical piece with with a blast I’m sorry, my brain is fried.

[00:43:52] Miko Lee: No worries. A musical. Wow. What is that about?

[00:43:56] Sam Chanse: Yeah. I think, you know what? I should double check because it said, I realized I’ve been working on it, but I should wait to check with my collaborators to make sure it is something I can share. I’ll hold on that. But it isn’t, this is about family and women. We’re an Asian-American, it’s an agent. It’s an Asian-American story, but I feel like I will hold them that. Okay. No worries. It’s okay.

[00:44:18] Miko Lee: Okay. So I have this bizarre fixation on watching hospital shows. It must be my a million cousins that are doctors and this kind of as an artist, longing to have a different life. You are a writer on the good doctor. What is that like for you? Are you one, are you still doing.

[00:44:39] Sam Chanse: I just wrapped two seasons. I’m like, I believe I am expect there. The next season will start soon and I believe I am going back.

[00:44:49] Miko Lee: Okay. So where do you get the story inspiration for the storylines on Undoctored shows a good doctor.

[00:44:57] Sam Chanse: It’s really great. So I, I feel it’s they have these medical consultants come in the show that brings in like a neurosurgeon and another doctor who share a lot of stories of what they see. Nobody there’s one person out who’s also, one of the writers is also a doctor and a medical doctor. So he also has a lot of input and a lot of perspective on that. And then we also just do a lot of our own research, but we get these, there are these two really amazing doctors who come in and share so much of what they know and share some medical ideas and then a lot of what the writers. His job is to find like the personal stories to weave in because none of us are trained doctors at all and are pretending to know what medicine is. No, and a lot of people are very informed at this point about medicine, but

[00:45:45] Miko Lee: one of my problems with so many doctors shows is the lack of Asian American representation on those shows. But the good doctor is one that has had a really strong Asian American characters. Is that, so do you specifically write for those characters or infuse part of your API identity into those parts?

[00:46:07] Sam Chanse: I do when I do it naturally, I think I’m always instinctively writing, infusing those characters with what I, with my perspective. And I think that’s part of what I can contribute to the show. And there’s another Asian American writer on the show and of course Daniel Dae Kim they can live as the AP one of the views. So I think it’s really wonderful to have that because. It’s so important to it’s how I’m, it’s a big lens for me when I’m watching anything. I’m like, what is Asian American representation? And that’s something I appreciate that they’re open to that, receptive to that kind of those kinds of contributions.

[00:46:41] Miko Lee: Thank you for doing that work. One of the questions that we are throwing out to all of our guests today is what is a piece of your AAPI and sessional knowledge that you want to share?

[00:46:51] Sam Chanse: My dad is haka. My, my mom is Pennsylvania Dutch and my dad is haka and he was born in Guan Jo. But for some reason, I only learned when he, yeah, this week or he may have told me I was young, that. That’s where my grandmother, his grandmother grew up. And I guess as the haka center, a pocket, someone probably knows this and is listening to me like she doesn’t know, just talking about I’m sharing what my father shared with me about my ancestral heritage. So I mentioned being a part of where our family comes from.

[00:47:22] Miko Lee: Thank you so much, Sam chance for joining us. People can check out monument or four sisters, a sloths play, which runs May 12th through 29th at the magic theater. It’s a world premiere. So hope y’all can be there. Thanks Sam.

[00:47:37] Sam Chanse: Thank you so much for having me on and talking with me. Have a great rest of the show.

[00:47:43] Miko Lee: Yes. Thank you. Next up. Listen to Mark Izu’s. Come on. Let’s go from his circle of fire album, featuring James Newton and G he Kim we’ll hear a full interview with the legendary Mark Izu at our API. Month’s special on May 31st.

[00:50:00] Jalena Keane-Lee: Come on. Let’s go next. We talk with the Ophelia Chong founder of Asian-Americans for cannabis education and stock pot images. Thank you so much for joining us Ophelia.

[00:50:12] Ophelia Chong: Hi, thank you so much for having me on it’s a beautiful Sunday and it’s just amazing that you’re doing this. So I’m very honored to have be on the show. Thank you very much.

[00:50:23] Jalena Keane-Lee: We’re so excited to have you, and it is such a beautiful Sunday and it’s the first day of Asian-American Pacific Islander heritage month. So we’re talking to a bunch of different people just to kick off the month in the right way. So I’d love to hear about stock pot images and the importance of creating images and just crafting images in general. How did you come to, to start that?

[00:50:48] Ophelia Chong: Oh, that’s a very good question. And it goes back 30 years, I graduated from ArtCenter college of design in fine arts and photography. So my first job was shooting for Reagan. It was a Seminole music and art magazine, and I shopped for them for three years, traveling to shoot bands, fashion certain editorial pieces. Then from there I was headhunted into digital music, sorry. Music labels, and from there into publishing and then into stock photography or early, late 19 hundreds or 1999 to two thousands. And so I was always in the realm of creating images, to creating something that has this may no translation. You don’t need words for, it’s just an image. So I’ve been doing that for about three years and stockpot photography. When my sister who is ill, came to this country to try and use cannabis, to help with her condition and as she was using it. But it was both, we were both neophytes at this point because also I was I’m a alcoholic, but I’ve been sober for 17 years. So to this fishing, for me to get a medical license, to help her with cannabis was a very big step for me. So I went and got her some edibles they had no idea, right? You have these two Chinese women, no idea what they’re doing.

So I gave her an edible. Didn’t go off so well. But when I looked at her, I thought, Hey, you don’t like a stoner. And then I started crying because I was not only stereotyping my sister. Something that we normally call other people about any forethought, something that I just stood there, realize this is not good. That was a moment. I began a stockpot images to demystify II and take away all the stereotypes of cannabis users that includes BIPOC Asian-Americans, children, women, everybody veterans. I created the stock agency that dealt with cannabis and I was the largest one. And I part with Adobe, but out of that, which more relates to Asian American month Adriana is back in the industry. I saw no one that looks like me. I would walk into a room and be marshmallows. And I’m looking for the reason. And so I realized from that point, it was. I had to educate my own people about cannabis because I was ignorant. I was that person. And so I created Asian-Americans for canvas education and try to find other people like me in the industry in 2015. Again, it took a long time finding people who wanted to come out of the closet to talk about it because of our heritage. However, since then I have probably over 60 interviews now with every strata of the cannabis industry of Asian-Americans. And so that is my story of today with Asian-Americans in cannabis. And I’m so happy you asked that question. It was a long way.

[00:53:58] Jalena Keane-Lee: Oh, no problem. And I was so impressed by Asian-American for cannabis education and all the different articles that you have in interviews. And I didn’t realize that there were. Asian-Americans in high level positions at all these different companies like packs and just across the board. So it’s very empowering to see. So thank you for highlighting that.

[00:54:17] Ophelia Chong: Oh between us Asian Americans my most recent interview with Steven Jones the COO of packs, which is a major company for hardware. Now they’re touching a plant. I talked to Steven and after hearing his story, I said, you are every Asian-American parents wet dream. He said, why is it you went to west? You went to Columbia. You are, you were captain in the army, you were at a startup called Twitter. Then you were president of Weedmaps and now here you are at PAX. And he looked at me and says, yeah, you’re right. It is people like that. Now entering the industry who have seen beyond the racism and stereotyping of cannabis users. And why I think that’s important is because we stereotype BiPAP people color, and we lump them all in as those people. The more I educate Asian-Americans about cannabis, I’m hoping that we left behind the racism between our articles.

[00:55:21] Jalena Keane-Lee: Yeah, I’m glad you brought that up. I’d like to talk a little bit more about this stoner stereotype and how it plays in to racism, especially with a historical lens. I know you’ve talked a lot about how for everyone getting in the industry, it’s really important that they know their history of weed and of, how it’s been used in this country to be really divisive and to be racist. So I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more about that and specifically in Asian-American communities, how that comes up as you’re talking with different people.

[00:55:46] Ophelia Chong: The here’s what’s been happening and I’m glad you raised that point is because during the last administration we’ve been made the villain. Anyone who looks like this, right? Regardless of whatever country came from, if we looked Asian, we were a target, right? And in our culture, we don’t normally speak up. I knew, remember growing up as a child, I was quite about seven years old holding my father’s hand as some woman who is older than my dad came up to us and first screaming for us to go back to her own country. I watched my dad stand there and not say a thing. I didn’t know what to do as a child, but now when I re go back to that, I wish she had said something because it’s, you do not fight back. Then you are going to always be stepped on. And I’m not saying fight back in a physical sense, but spike back with education and with reaching out to people and say, this is who we are. Can we leave? And so in cannabis, it’s the same thing too, because I’m talking to Asian Americans about cannabis and say, let me tell you what this is.

Let me take away the fear because in our society we’ve been using mushrooms and cannabis and hemp for over 10,000 years. So why are we now taking our own heritage and saying no to it? So that is part of the education on the cannabis side, but also on the active and the side to say, we will not stand for this. And so it’s a two different answers, but it, to me they formed. One is basically reaching out, educating people about who. And I reached out to people about what cannabis is. So it’s a mix and match there.

[00:57:35] Jalena Keane-Lee: I love that. And I am a cannabis user myself and also a filmmaker. And I saw that you were the creative director of slam dance for quite a while. And I’m curious how your background in film and in all the different art forms that you know you have participated in. How has that shaped specifically this point about the information and doing some of the education pieces around cannabis? Oh, that’s a great question too, because that’s again a two pronged question.

[00:58:07] Ophelia Chong: I was a creative director for slam dance for 10 years, but also for strand release releasing, which is a LGBTQ foreign film company. So we refilled all the small, independent films. New York film, festival Tribeca, all that. And so I worked with a lot of groups that were marginalized, because of culture, ethnic group or choice of lifestyle, and with that, it brings a hurricane and more of a knowledge of what we’re doing and how to present that how to speak to people in other groups. So when I speak about cannabis or Asian Americans is looking at who I’m talking to, how I can reach them through their a portal that they understand. If that makes any sense, it’s basically sitting and listening. That’s how you change people. You sit and you listen, and then you give them back something that they can understand. I hope I answered your question.

[00:59:02] Jalena Keane-Lee: Absolutely. And we’re just going to pause quickly for a station ID on the hour, but then we’ll be back with our last question for you.

K PFA is America’s original listener supported radio station. Yes, we’re the place on the dial that speaks truth to power, but we’re also a music discovery platform. Music is part of the genetics of KPFA. We connect bay area music lovers to John Lewis at inspired creativity. Help us continue to share the magic of jazz blues rock funk, R B gospel world and classical music by making a [email protected]. Maybe you’ve been listening for. Even decades and you appreciate how important KPFA is in your life. If you’re a forward-thinking donor who wants future generations to benefit from KPFF and unhindered creativity, then join KPFA legacy. And include KPFA in your will or living trust for details. Visit our [email protected]. Thank you. please join KPFA for a special zoom event on Thursday, May 5th at 7:00 PM. When we welcome mark foam and his debut book triggers. Inside the mission to stop mass shootings in America, hosted by KPFA Dennis Burns team trigger points is a strong argument for a more proactive approach to the American pandemic of bullets. And as an optimistic take on one of America’s most distressing problems, take us for this fascinating evening are [email protected]. you’re listening to 94.1 KPFA 89.3 KPFA in Berkeley, 88.1 CF in Fresno, 97.5248 in Santa Cruz and online, [email protected].

And we are back with Ophelia Chong, founder of Asian Americans for cannabis education. Thank you again so much for being. And I really want it to pick up on what you were talking about with cannabis use and mushrooms use being very ancestral and part of our practices for healing for a really long time. And building off that, I’m curious if there’s a piece of API ancestral knowledge that you’d like to share.

[01:01:31] Ophelia Chong: Wow. That’s a very big question. So for anyone who wants to really delve into how much plant medicine knowledge that we have in our history and our Asian history, and I’m talking about all Asians, it’s incredible because you remember your grandma or your great mom, grandma making. There’s all these funky things going into it, but she’s making it because your mom or your dad or their husband is sick. And you remember those smells and going into these grocery stores have to go to your parents and go, wow, that’s a lot of dry stuff and they’re just buying it and they’re throwing it in and they’re measuring it and making these amazing tonics that we look at.

And then you realize when you go to whole foods or any other Erewhon any grocery store and you see the same tonics there and you realize. People who are not Asian, no more about your culture and you do I really encourage people to just go into any apothecary that is our herbal medicine store and just stand there and take it all in and look at all the knowledge that is out there that you can at least supplement your health with things that are not pharmaceutical, but also comes back from our ancestral of 10,000 years ago of how we heal with what we were growing, because Asians are agrarian society.

We grow things. We’ve always been growers and farmers and what we took from the land we put back in, but also we respected what we took and use that for our own health and regenerated it back again and brought it into the future. Like handing down these recipes over and over again from mother to daughter to sign to everybody. So I would encourage people to talk to their family and say, Hey, remember that stupid used to make. Tell me about that and make it themselves. Enjoy your history, eat your history and learn your history.

[01:03:46] Jalena Keane-Lee: Okay. I love that. Thank you so much. I hope everyone has an opportunity to enjoy, eat, and learn their history this month. Thank you so much for joining us Ophelia. Next step we have Mark Izu’s threading time.

[01:05:39] Miko Lee: that was Mark Izu’s threading time, an ode to his sensei. Togi Suenobu who plays hichiriki on this piece.. And as we mentioned earlier later on the end of the month, we’re doing another special on May 31st and mark easy. We’ll get a full interview with him about his brilliant career. So Jalena what have we heard so far this morning?

[01:06:01] Jalena Keane-Lee: We’ve heard a lot of great stuff. Some of the stuff Ophelia was talking about is still really sticking with me though, especially about, the smells and seeing. Your own ancestors, your own relatives, use herbs and create healing selves.

[01:06:15] Miko Lee: I often think about that as you sit here with a bottle of kombucha tea that we paid a lot of money for it.

[01:06:23] Jalena Keane-Lee: It’s actually water,

[01:06:24] Miko Lee: sorry. It’s in a kombucha bottle. And my grandma, my Popo always had a SCOBY in the fridge, which I thought was stinky and tasted bad. And I associate with being sick, but you love that stuff.

[01:06:37] Jalena Keane-Lee: It’s true. I think its gift to generations and how she would drink apple cider vinegar. That’s very me every morning.

[01:06:44] Miko Lee: That was her whole tip for survival. And she never went to the doctor. And in fact that eight kids in the family that grew up in Madera and then Berkeley never ever went to the doctor. Except when my one aunt got gravely ill, but other than it was all natural remedies.

[01:06:59] Jalena Keane-Lee: Thinking of what she was saying about like smell and how smell can trigger memory so much. And yesterday we went to neons, never bright. In San Francisco, Chinatown, which was such an incredible event. And we got to meet in person, the artists, the scent artists who

[01:07:16] Miko Lee: Yosh Han

[01:07:17] Jalena Keane-Lee: who my mom interviewed for our last show. And we got to smell the sense that they created for the event. And they had the scent broken down into the four different, I don’t know what the correct jargon is, but the four different scents that were put into the main sense of the event. And one of them was that medicine.

[01:07:34] Miko Lee: So the scent is called longevity, which for me that was like, what, how can you create a set for longevity? But one of the things was this medicine that’s like tiger balm. It has a little bit of a tiger balm, but a little bit more eucalyptus

[01:07:45] Jalena Keane-Lee: really., it was like white seed oil right?.

[01:07:47] Miko Lee: I can’t remember the name of it. Exactly. But there’s that. And then there’s Jasmine and what was the other two smells? There are another two that were there.

[01:07:56] Jalena Keane-Lee: I’m not sure, but they smelled good. And they had said that the medicine was the scent that was bringing up the memories for everyone,

[01:08:04] Miko Lee: the memories of childhood.

[01:08:05] Jalena Keane-Lee: Yeah. And that event was put on by Chinatown media and arts collaborative, which is a coalition of a bunch of different Chinatown organizations. And the intention was to bring light and life and laughter and art into San Francisco, Chinatown to kick off Asian-American Pacific Islander heritage month. And also. Yeah, to bring life back into Chinatown after what’s been a really hard few years, as we all know,

[01:08:30] Miko Lee: and it was lovely because we got to do traditional ceremonies and there was lion dance. There was these hung bow, which are red envelopes that we pass out for new years with the scent and then actually beautiful photographs taken by the artist, Billy Ola Hutchinson. And then there were site-specific performances and then such a lovely short films created by James Chen, which we are interviewing. And you’ll hear from on our May 5th episode on Thursday, but then also talk about the fashion show and the whole thing of,

[01:09:03] Jalena Keane-Lee: so it was really fun. They had two documentary or three documentary shorts. One was really short, but yeah, I think three, but two of them were about these two different designers. And so it was really cool to see their design process. Style and everything. And then there were two fashion shows for each of the designers. And it was really fun seeing that and seeing it in the theater that we were in. Why don’t you talk a little bit about that theater and the kind of significance that holds for you?

[01:09:29] Miko Lee: So this is, I think it’s the four-star. Is that right? Can you look up the name of the theater? Only remaining theater in Chinatown, which used to house Chinese operas and movies, and they have remade it. And so it’s still there as this lovely living legacy. And I have these memories of being dropped off at my grandparents’ house in Berkeley and going with my cousin, Robbie with my grandpa, taking us to see Chinese opera and then re crazy movies about monkey king at this movie theater. And the fact that it’s still there right around the corner from Portsmith square and is actually a beautiful place. And we were able to see one of the short films was about the artists. Amazing. And icon Victor tongue and he showed his fashion. And then there was like a kind of, professional version of of a fashion show of his works. And then the other was on dot

[01:10:27] Jalena Keane-Lee: polka dot.

[01:10:28] Miko Lee: And she is 80 something year old artist activist.

[01:10:33] Jalena Keane-Lee: 88,

[01:10:34] Miko Lee: which is really a suspicious Chinese numbers. And she showed up decked out with a whole Lee lion dad’s hat, which I loved. And they had all these different ages doing a catwalk of her personal fashion over the years, which was so charming to me.

[01:10:55] Jalena Keane-Lee: And my favorite was she had a protest sign that said crazy poor old Asians. That was really funny. And she had a lot of impeach clothes as well.

[01:11:07] Miko Lee: Yeah, she is really an activist and it was just so powerful to see her still doing. I love that. Like I want to grow up and be feisty like that.

[01:11:16] Jalena Keane-Lee: You are. And that was at the great star theater the iconic movie theater in Chinatown. I also really resonated with what Sha was talking about with just. The importance of placing indigenous voices front and center. When we’re talking about climate change and climate movements, and also, AAPI being something that’s very broad and encompasses so much land and so many different cultures and people, and to make sure that as she said, the PI is not silent in that AAP.

[01:11:47] Miko Lee: Yeah. And she is from a small place called Palau, which a lot of people don’t know, Palau is a country that’s in the Western Pacific ocean. And it is, oftentimes we don’t think about all these Pacific islands that are a part of the United States dates areas that the United States have colonized Palau is in the corner of Micronesia, which is a whole series of islands that our United States government did nuclear testing on. And so still to this day, there are when you go into these countries, you actually have to go through an entire scanner with your body to make sure that you are not. Yeah, bringing in, you’re not taking out nuclear. I don’t know what it would be on your body. But it’s very intense how these beautiful islands and plow is known for being one of the best scuba diving places in the world. People often see these amazing pictures of swimming through all these jellyfish, which is in a lake in Palau. And yet at the same time, this is a place that our government has really desecrated in many ways with nuclear testing.

[01:12:53] Jalena Keane-Lee: I also like how Sha, I didn’t mention this during the interview, but she identifies as a vigil auntie. The, I G I L and then auntie, and I think that’s really cute. And I love the, I think just like a radical auntie. Although next time we talk to her, I’d love to talk with her more about what that means for her, but I just really love the auntie identity and stepping into that and claiming that, especially in a radical and activist center,

[01:13:18] Miko Lee: Yeah, that is amazing. One of the other, we’re going to next week on Thursday, we’re actually going to talk about all these different events that are coming off for AAPI a month in may. And so we’ll talk more in that time about CAAMFEST, which is the center for Asian American media and all the shows that they’re doing. Also, they’re doing a collaboration cam center for Asian-American media is doing a collaboration this month with SF MoMA. So people can go there and check that out. And they’re also doing a documentary series.

[01:13:46] Jalena Keane-Lee: Yeah. They’ve partnered with a doc, the Asian-American documentary collective and world channel to pro to co-produce Asian American stories of resilience and beyond a series of seven documentary shorts that move beyond the pandemic and reflect the complexities of AAPI experiences in this critical moment and center for Asian-American media cam and campus was formerly known as the San Francisco film festival. So be sure to get tickets for that. And I’m sure they’re going to have a lot of great films to share this.

[01:14:16] Miko Lee: And next up, we get to talk with the quite brilliant and amazing Dr. Connie Wun jalena’s gonna chat more with Connie who we adored and so powerful.

[01:14:28] Jalena Keane-Lee: And Connie is the co-founder of AAPI women lead. Thank you so much for joining us.

[01:14:37] Connie Wun: Hi friends. Can you all hear me?

[01:14:39] Jalena Keane-Lee: Yeah. Thanks. Thanks for joining us bright and early on May 1st, I’m curious as we start the month, Asian-American Pacific Islander heritage month, what are some of your intentions? For this month of may this year.

[01:14:53] Connie Wun: Thank you for having me on the show and thanks for having this celebration generally speaking. And that question is great. Some of the intentions that I have it’s multi-layered for the organization, AAPI women need, we want to make sure that we amplify some of our most marginalized communities that includes our Pacific Islanders, our native Hawaiians, our Southeast Asians, our migrant workers, our elders, our youth, our sex workers are incarcerated communities.

So I’ve one of our main goals and intentions. And then we’re also making sure that we amplify the need for emotional, mental and spiritual health healing and recovery from a really challenging few years. Lifetimes. So we’ll be bringing on a couple of our mental health practitioners and spiritual health practitioners. And then I think the third intention is around systems change. There’s so many conversations that are extremely important about representation, about making sure that all of our communities are represented and reflected. But I also think to add to that as a need to do it for a systems change and to create a different world, not just to put really beautiful faces on the screen, on the radio, but for us to actively work together, to create a different world. So those are some of the kind of broader intentions that I would love to share.

[01:16:18] Jalena Keane-Lee: Absolutely. And there’s so much that we could talk about within all of that, but I’m glad that you brought up healing and I’m curious how have your personal healing practices evolved in the past year or so?

[01:16:33] Connie Wun: That’s a great question too. I have been a meditation practitioner for about three to four years. I’ve found myself relying on meditation quite a bit twice a day, early in the morning, what, before I go to bed and that’s been very grounding and I’ve had to really commit to that. Especially under the pandemic and with all the different forms of violence I just returned to martial arts and that’s been very healing. I’m a fan of embracing my rage. So when I practice more time, I get to hit the peds and I get to kick the pads and the bags. That’s super healing for me. And then of course I’ve been practicing yoga for about. 22 years. And I just went back into the yoga studios. And while I’ve been practicing for about 20 something years, I’m going to have to say this was the first time, about two weeks ago that I actually felt my mat. Like I have been so scattered that I’d only now actually literally felt my feet on the mat. And that was a huge I guess I was a huge healing moment for me. So those kinds of practices and I gained, I’ve taken up to writing. I’ll keep it real. I have two therapists. That’s one that feeling in recovery I’m I’m invested in and they’re all women of color. So those are my healing practices out of the.

[01:18:02] Jalena Keane-Lee: Thanks for sharing. And what are some of the highlights of your year so far when it comes to your work with a BI women lead? This year?

[01:18:11] Connie Wun: It’s may Ooh, so there’s, there are a few, one is we are launching our community driven research project and it is to my knowledge, the first of its kind but it’s a national project and that includes people in the us and our affiliated territories. There are currently 14 community researchers across 11 organizations and we are focusing on collecting our community stories around racial and gender violence. It’s the first of its kind where it’s community driven community powered. And our organizations are from Iowa, Wisconsin, New York Georgia Atlanta the bay area American Samoa, Hawaii, Boston.

So I think we’re also in Maryland, so we’re actually everywhere and this is the first of its kind. And we are actually also focused on transformative justice. So we coupled and partnered with other abolitionists, transformative justice organizations to beat this. And that’s a huge source of pride for me because I’ve been working on it on fundraising for this for five years. And we launched it. So that’s huge. And then the other thing is we got to do a screening for everything everywhere, all at once. We hosted a screening. I think you all were there, which was great. And we got to show off, our talented Michelle Yeoh are numerous actors in and in the film. So I think that was really great partnering with gold house to do that. And CAPE to make that happen. And these are all also entertainment based national centers.

[01:19:51] Jalena Keane-Lee: That’s great. Yeah. We, we’re huge fans of the movie, so thank you so much for putting that event on and for all the work that you’re doing. I’m curious if you could talk a little bit more about the relationship between representation and systems change like you were talking about, and maybe if that relates to joy and the importance of joy and activism as well.

[01:20:10] Connie Wun: I think representation is so super important in all fields of our in all areas. I think however, while representation is paramount cause I think it’s very important for us to see each other in certain spaces, especially in dominant spaces. But my hope persistence change is that when we’re in these spaces, we’re actually working to create systemic change. Very firmly rooted in this belief that there has been a lot of harm that has been committed against Asian and Pacific Islander communities, black communities, Latin X communities, indigenous communities here and across the globe.

And so when we’re in these spaces that we seek representation in, I hope that we’re doing that because we want to change the systems that have been so violent to our peoples. And not just because we want a seat at the table, but that we have a critique of the table and that we know that the table has caused way too much harm. And perhaps we might need to do away with the actual. So that’s what I mean by representation and systems change. I think what I find joyful in that is that there are so many generations that are very excited about doing that. I think our younger generation are, they’re just brilliant. And I think, whereas in my generation, was the first born here in Oakland, California, Vietnamese, family, Vietnamese war refugees. We, there weren’t any Vietnamese anywhere when I was growing up, there were maybe like six of us and, growing up that way, everybody either thought I was like strictly Chinese or had no clue where Vietnam was, which is really racist and strange. But now that there are so many more of us I’m excited to find out what kind of work we’re going to do to make this place.

I’m following the leadership of young people who are doing so much tremendous work on balling the work of other sex workers in formally incarcerated communities who have so much power in their stories and their experiences, and so much wisdom that definitely brings me joy. It amps me up I think knowing that more people who have been marginalized or made really vulnerable or are unresourced or under-resourced in this country are rising up and refusing and resisting that that history. And I’m extremely excited about that leadership. I’m excited about that. So many more young people are embracing their rage. That excites me, I remember going up and there was representation on TV. It would be yellow face. All the time and it would be white people saying something that was supposed to pass to something Asian. I just saw a post where young people are like, ah, actually never again. So that brings me a lot of joy. It’s not just three people who are upset, but like thousands and thousands upon millions of people are like, Nope, that’s not happening again. That brings me a lot of joy

[01:22:58] Jalena Keane-Lee: and speaking of rage and, righteous rage and how that can be channeled into so many beautiful things. I want to talk a little bit about safety and, as an Asian American femme, what are some of the conversations you’ve been having around safety and what are some of the personal safety practices? Both physically, mentally, all of the above that you have been putting into practice in the past few years?

[01:23:24] Connie Wun: I really love that question. And it also speaks to, again, you’re, Asian-American fem I don’t know if you identify with this, but your feminist framework because people were barely ask us that question around safety. So that has been at the forefront of a lot of my thinking in the past couple of years in the organizing world. And even when I’m on TV and different interviews, if I were to say anything around being against white supremacy or even being against patriarchy, the backlash that I would experience included doxing threats harassment online. If I said anything about solidarity with other communities of color, I definitely received a ton of threats. And that would be cyber threats. We would also receive threatening emails or not emails. Yes. Emails, threatening emails, and then threatening postal mail sent to her PO box. So I appreciate you offering me the space to talk about how compromised our safety was as Asian femmes. And feminists, when we spoke out that has led me to withdraw from the public platforms a lot, to be honest for a while I had to decline interviews, including from major networks because I was receiving way too many threats.

And I think the important part is that I was reminded that these breads they couldn’t allow for them to. Because for a second, they were really frightening. And so what that’s meant is that we have implemented different cyber strategy, fiber site safety strategies. So that’s, the digital security has been really important and that’s actually been led by a lot of sex workers. So I want to amplify in the bank, people in the sex trade who have been doing work on the, with the cybersecurity we’ve implemented digital security in terms of physical security. I do have to say that AAPI Women Lead has been partnering with our martial artists, our bystander training trainers to make sure that our communities embraced and recall and reclaim our traditional healing practices and our combat practices, which is martial arts. So we’ll have MMA fighters come in and host self-defense and community defense trainings. So that’s two levels, right? So security. And then self-defense but we’re also very big on community events.

We don’t want to put it on the onus, or we don’t want to put the onus on the survivor or the person who’s being harmed in order to defend themselves. We make sure that people are trained in bystander training. We also recognize that this is about, when we’re attacked, it’s about patriarchy. It’s about xenophobia. It’s about racism. So safety for us. It’s also about systems change. So it’s multilayered digital security, community safety self defense, and then about system change. I do want to add that we’re also very big on mutual aid. Self-defense so APL and the me just put put together 300 plus COVID tests and packets together in multiple languages that too is a form of self-defense and safety. We’re thinking about disability, justice as safety to make sure that our elders, we have one of the highest population of elders who are also disabled and immunocompromised. So we’re making sure that tests are out to our elders, but they also have not right. That is a part of safety of our community as well. So it’s super layered. But that is actually very central to our organization. And it’s very central to how I think, as a Asian

[01:26:59] Jalena Keane-Lee: Thank you so much for sharing that. And, after hearing what you just said and seeing the tribute to Michelle Yeoh over the weekend, I’m ready for some ancestral combat in my life. And I’m curious, what kind of thoughts, or what advice would you give to someone who is, maybe just starting to be a bit more vocal about their activism, but is afraid for their safety, seeing what people like you have had to go through in that space specifically in the social media space.