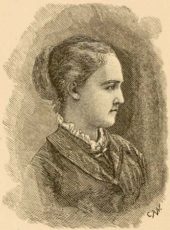

Today’s show is an examination of the work of the unjustly forgotten American poet, Sarah Morgan Piatt. Sarah Morgan Bryan Piatt lived from 1836 to 1919. Emily Dickinson lived from 1830 to 1886, so they were near contemporaries. Dickinson was a prolific private poet but fewer than a dozen of her nearly 1,800 poems were published during her lifetime. Sarah Morgan Bryan Piatt was a well-known literary figure who published some 450 poems in eighteen volumes and in leading periodicals of the day. In 2001 the University of Illinois produced Palace Burner: The Selected Poetry of Sarah Piatt, edited by Paula Bernat Bennett. Piatt was friends with both Walt Whitman and—because her husband, poet John James Piatt served as American Consul in Ireland for eleven years—William Butler Yeats, who in 1893 reviewed and praised her work.

Today’s show is an examination of the work of the unjustly forgotten American poet, Sarah Morgan Piatt. Sarah Morgan Bryan Piatt lived from 1836 to 1919. Emily Dickinson lived from 1830 to 1886, so they were near contemporaries. Dickinson was a prolific private poet but fewer than a dozen of her nearly 1,800 poems were published during her lifetime. Sarah Morgan Bryan Piatt was a well-known literary figure who published some 450 poems in eighteen volumes and in leading periodicals of the day. In 2001 the University of Illinois produced Palace Burner: The Selected Poetry of Sarah Piatt, edited by Paula Bernat Bennett. Piatt was friends with both Walt Whitman and—because her husband, poet John James Piatt served as American Consul in Ireland for eleven years—William Butler Yeats, who in 1893 reviewed and praised her work.In the introduction to Palace Burner, Paula Bernat Bennett writes,

“To read Sarah Piatt as she should be read will mean…becoming considerably more open in what we look for and value in poetry itself. It will mean, that is, learning to read for values beside the word. With the rise of new schools of criticism that are socially engaged—in particular, the ‘new’ historicism and cultural studies—Piatt’s poetry, which is so deeply committed both to history and culture, may finally get the audience it deserves. If so, American women’s literary culture will be the richer for a poet of unusual complexity and depth. Without attempting to transcend her own time, Piatt, with a courage that verged on blindness, opened her poetry not only to the divergent voices of her period and culture but to those constituting her own fractured and multiple ‘self,’ a self that in its very contradictions, its liminality and its disguises, gave rise to a body of poetry that this introduction and this edition have only begun to explore…

“Piatt pushed the limits of Victorian language and the Victorian female persona as hard as she could, staging in her language a multiply fractured persona instead, a persona divided not just between North and South, but between love and anger, dove and tiger, romanticism and cynicism, piety and apostasy, submissiveness and rebellion. In one of her strongest poems…her speaker takes on God himself…” (“God has his will. I have not mine.”)

This is “Giving Back the Flower”:

So, because you chose to follow me into the subtle sadness of night,

And to stand in the half-set moon with the weird fall-light on your glimmering hair,

Till your presence hid all of the earth and all of the sky from my sight,

And to give me a little scarlet bud, that was dying of frost, to wear,

Say, must you taunt me forever, forever? You looked at my hand and you knew

That I was the slave of the Ring, while you were as free as the wind is free.

When I saw your corpse in your coffin, I flung back your flower to you;

It was all of yours that I ever had; you must keep it, and—keep from me.

Ah? so God is your witness. Has God, then, no world to look after but ours?

May He not have been searching for that wild star, with the trailing plumage, that flew

Far over a part of our darkness while we were there by the freezing flowers,

Or else brightening some planet’s luminous rings, instead of thinking of you?

Or, if He was near us at all, do you think that He would sit listening there

Because you sang “Hear me, Norma,” to a woman in jewels and lace,

While, so close to us, down in another street, in the wet, unlighted air,

There were children crying for bread and fire, and mothers who questioned His grace?

Or perhaps He had gone to the ghastly field where the fight had been that day,

To number the bloody stabs that were there, to look at and judge the dead;

Or else to the place full of fever and moans where the wretched wounded lay;

At least I do not believe that He cares to remember a word that you said.

So take back your flower, I tell you—of its sweetness I now have no need;

Yes, take back your flower down into the stillness and mystery to keep;

When you wake I will take it, and God, then, perhaps will witness indeed,

But go, now, and tell Death he must watch you, and not let you walk in your sleep.