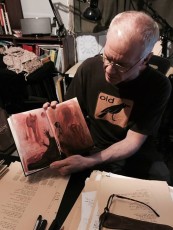

Jack’s guest throughout the month of October is the extraordinary Alabama poet, visual artist and musician, Jake Berry. Jack writes:

Jake Berry’s work is full of “totalizing perspective”: he speaks over and over again to the mind’s desire not to rest in any particular context. His poetry exists to manifest what he calls “pandemonium,” “idiot menagerie”: “to isolate one from the other is only useful in abstract explanation and there is no evidence to suggest that this ever occurs in nature…EVERYTHING IS EVERYTHING ELSE” (Idiot Menagerie, 1987). “The reader,” he wrote in a letter describing one of my poems, “is seduced into the knowing participation in chaos.” One is reminded of a remark the young Robert Duncan made in a letter to Mary Fabilli (quoted in Egbert Faas, Young Robert Duncan but never received by Mary): “Not to seek a synthesis; but a mêlée.”

In our society, poetry is a discredited tradition. “Books,” wrote Milton in the Areopagitica, “are not absolutely dead things, but do contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul was whose progeny they are; nay, they do preserve as in a vial the purest efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them…a good book is the precious lifeblood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life.” Echoing him in simpler prose in “The Hero As Man of Letters,” Thomas Carlyle wrote, “In books lies the soul of the whole Past Time; the articulate audible voice of the Past, when the body and material substance of it has altogether vanished like a dream.”

In our time, books have become, precisely, dead things, objects. We are inundated with them. If Allen Ginsberg was able to encounter Walt Whitman in the supermarket, we are much more likely to run into Dame Barbara Cartland. In affirming magic and infinity as the central issues of his poetry, Jake Berry is not merely dealing with a theme. He is attempting to turn his book into a power object—“like a totemic word or something”: he is conceiving of the book as something magical, alive, not merely expressive of himself but of something “other.” Berry’s work can be “deconstructed” if you like, but its importance lies in its powerful mythic thrust—a thrust which recognizes and takes on some of the most problematical issues of our culture. It is difficult to find much that is like it. It is able to include—and to transform—so much:

“There are deep red holes in the water.”

“Yes. But it’s safe.”

*

I buried my daughter

in asphalt &

On today’s program Jack reads an introduction to Jake Berry’s work and plays Berry’s own recording of passages from Book IV of the experimental magnum opus, Brambu Drezi—a mixture of language, moans, sounds, and avant-garde musical techniques.