A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists.

A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists.

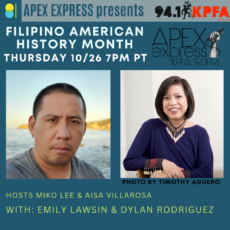

APEX Express celebrates Filipino American History Month. Host Miko Lee is joined by guest Aisa Villarosa.

They learn about the origin story of Filipino American History Month with Dr. Emily Lawsin and talk about the critical importance of ethnic studies with Dr. Dylan Rodriguez. We also get to hear music from Power Struggle’s Aspirations album.

More information from and about our guests

Filipino American National Historical Society

Dylan Rodriguez and his writing:

- https://www.beyond-prisons.com/home/dylan-rodriguez-part-i-abolition-is-our-obligation

- https://millennialsarekillingcapitalism.libsyn.com/white-reconstruction-dylan-rodriguez-on-domestic-war-the-logics-of-genocide-and-abolition

- https://www.blackagendareport.com/cops-colleges-and-counterinsurgency-interview-dylan-rodriguez

Musician Power Struggle and their collection:

https://beatrockmusic.com/collections/power-struggle

APEX Express Episodes featuring subjects discussed in this episode:

- 11.8.18 – Dawn Mabalon is in the Heart – entire show dedicates to Dawn

- 11.18.21 – We Are the Leaders – Labor features Gayle Romasanta on Larry Itliong book co-written by Dawn Mabalon

Show Transcript Filipino American History Month 10.26.23

[00:00:00] Miko Lee: Good evening and welcome to Apex Express. This is Miko Lee and I am so thrilled to have a guest co host this night, the amazing and talented Aisa Villarosa. Aisa can you please introduce yourselves to our audience? Say who you are, where you come from, and a little bit about yourself.

[00:00:44] Aisa Villarosa: Thank you so much, Miko, and it’s a joy to be with you and the Apex Express family. My name is Aisa, my pronouns are she, her, and I’m a Michigan born gay Filipino artist, activist, attorney with roots in ethnic studies organizing and teaching Filipino studies, in the wonderful Pa’aralang Pilipino of Southfield, Michigan. If you ever find yourself at the intersection of Eight Mile and Greenfield near Detroit, stop on by.

[00:01:19] Miko Lee: Aisa, talk to me about this episode and what we’re featuring in honor of the final week of Filipino American History Month.

[00:01:28] Aisa Villarosa: I’d be honored to, Miko. We’ll be doing a deep dive into Filipino American History Month today, including its origins and how the month acknowledges the first Filipinos who reached the shores of Morro Bay, California in 1587. We’re going to be talking about what this month means in the context of today, how Filipinos are honoring the ongoing struggles for civil rights, for human rights, and we’ll be talking to some personal heroes of mine. We’ll also be talking about ethnic studies, which shares with new generations, these events and stories of Filipino Americans.

[00:02:12] Miko Lee: Aisa, talk to me about ethnic studies. What is the background that we need to know? It’s been a big part of our Asian American movement struggle with the fight for ethnic studies. give our audience a definition about what ethnic studies is and why is it important right now.

[00:02:29] Aisa Villarosa: That’s a great question, Miko. And I really love the definition of ethnic studies offered by the Coalition of Liberated Ethnic Studies. And they have said that this is essentially the knowledge, narratives, experiences, and wellness of Black, indigenous and people of color and their communities so that liberation of all peoples and relations are realized. And when we really break that down, this is the study of collective liberation. Part of why ethnic studies is so important is that this is really a root key to unlocking systemic change against hate. If it’s taught in an intersectional approach, it really is a preventative tactic against racism. It’s also rooted in storytelling. It’s rooted in multi generational learning. And the best thing, in my opinion, with ethnic studies is we see the community as a living classroom.

[00:03:32] Miko Lee: And , I know Ethnic Studies is part of your background. You came up as a student of Ethnic Studies. I came up in Women’s Studies and Theater Studies not Ethnic Studies, but I took so many Ethnic Studies classes at San Francisco State that really profoundly shaped how I work and live as an activist and artist. Can you talk about how being a Filipino Studies student impacted you in your present day?

[00:03:57] Aisa Villarosa: Absolutely. And oh, Miko, I feel like we would just be nerding out together in a theater or activism class. So thanks for sharing. Quite simply, I wouldn’t be who I am without Ethnic Studies and the incredible folks behind this movement, including some voices that we’ll be hearing from soon. It is encouraging that even in California, for example, ethnic studies was mandated in high schools in 2021. We are seeing a lot of progress across the nation with more and more school districts, more and more classrooms incorporating ethnic and Asian American, Pacific Islander, Native Hawaiian studies.

And yet we also know that passing a law to teach ethnic studies is but one step and this isn’t very well known, but ethnic studies is actually under attack. It’s under attack from attempts to censor and limit the history and teaching, especially around colonization and militarization experienced by communities. And why this is really problematic is this sort of censorship can keep communities from finding one another, from finding that common ground, from seeing each other in their full humanity.

[00:05:18] Miko Lee: Aisa there’s so much going on in our world right now with what’s happening in Palestine and Israel. And what does this have to do with the work of ethnic studies?

[00:05:29] Aisa Villarosa: It has everything to do with ethnic studies, and right now we’re seeing some targeting of students and activists speaking out for nonviolence, for a ceasefire, and an end to military occupation in Palestine, in Hawaii, across the world. And these activists and young folks are being targeted really, As Palestinian identity and people endure tremendous loss and mass displacement, why this matters is ethnic studies is living history and ethnic studies challenges us to take stock of moments where we can either be silent, or we can take action, including first steps to understand the history and the narratives behind these conflicts to really unpack the global impacts of colonization. It doesn’t matter whether one is Filipino or Asian American or Black or Latinx or Indigenous or from any one of the countless communities living under the impacts of systemic violence and oppression.

[00:06:36] Miko Lee: Thank you for sharing. I feel like we could do a whole series on why ethnic studies is so critical and important. But look forward to hearing from two people that are professors, educators, and activists and tell me who we’re going to be talking with first.

[00:06:51] Aisa Villarosa: We’ll be talking first to Ate Emily Lawsin, a poet and an activist. She’ll be sharing more about the establishment of Filipino American History Month.

And then we’ll be talking with activist and scholar Dylan Rodriguez, about Filipino American history in the context of today’s struggles against white supremacy, military exploitation, and government violence.

[00:07:16] Miko Lee: So let’s take a listen to our interviews.

[00:07:18] Aisa Villarosa: We are here tonight with one of my dearest mentors, heroes, big sister, a. k. a. Ate, Ate Emily Lawson. Emily, you have, over the course of your career, taught and made a difference in thousands of people’s lives, including mine. For folks who are just getting to know you, can you share a little bit about your work and perhaps, you working on right now?

[00:07:49] Emily Lawsin: My name is Emily Lawsin and I’m a second generation Filipino American, or pinay, as we say. I was born and raised in “she-attle” Washington and I’m the National President Emerita of the Filipino American National Historical Society or FANHS. I was on the board of trustees for 30 years no longer on the board, but still do supportive work for the organization. It’s a completely volunteer run organization founded by Dorothy Ligo Cordova, Dr. Dorothy Ligo Cordova in 1982, I used to teach Asian Pacific Islander American studies and women’s studies at different universities across the country in California and other states I was really blessed to be able to teach some of the first Filipino American history courses on different campuses and really utilize our FANHS curriculum in doing that. Now I work for four Culture which is King County’s Cultural Development Authority, and I’m the Historic Preservation program manager there. I’m also a spoken word performance poet and oral historian

[00:08:59] Aisa Villarosa: and for folks who have not had the privilege of watching Emily perform. You are a powerhouse. And a confession, I have inspirational post it notes around my laptop and I have one post it that says no more moments of silence. It’s from a performance you gave, gosh, it was maybe sometime in 2008,

[00:09:22] Emily Lawsin: yeah, that’s awesome. Oh, thank you.

[00:09:25] Aisa Villarosa: Yes. It’s come full circle because I have remained a supporter of ethnic studies and part of why I am talking with you today is because October is Filipino American History Month and even breaking down every single word.

In that phrase, there was a battle and a journey to even get the national recognition that y’all were able to get especially through your advocacy. So if you could tell the listeners maybe a bit about that journey and even for folks who are newer to the month, what is the difference between, say, heritage and history?

[00:10:08] Emily Lawsin: Oh, that’s awesome question. Thank you. Yeah, Filipino American History Month was really started by my Uncle Fred Cordova, Dr. Fred Cordova, who was the founding president of the Filipino American National Historical Society, or FANHS. He came up with the idea in 1991 and really wanted to recognize October as Philippine American History Month because the first documented landing of the first Filipinos in what is now known as the continental United States, specifically Morro Bay, California, happened on October 18th 1587.

When Lizones Indios or Filipinos who were a crew and a slave slaves really on Spanish galleon ships were sent ashore off the coast of Morro Bay as like a landing party to scout out the area. If you actually look at a Instagram reel that our current FANHS President, Dr. Kevin Nadal made he tells you the history of, why October 18th, 1587 is important and it’s not necessarily to celebrate that landing because people did die.

But it’s to commemorate and to remember that history and that memory where a Chumash Indupinos. Indigenous Filipinos Indupinos is what they call themselves too. They actually were instrumental in creating that moral based site as a historic marker for FANHS. That date is significant for Filipinos because of that first landing.

And Then in the 1760s the first communities and families were created in the Bayou of Louisiana. Where these same crew folks or Filipinos jumped ship from those Spanish galleon and were called Manila Men by Marina Espina, who wrote the book Filipinos in Louisiana. Those families that jumped ship, created seven different villages in the bayous of Louisiana and intermarried with the local Creole communities there. Those families are now in their eighth and ninth generations. We wanted to recognize that history as being really the first Asian Americans in what is now known as the continental United States.

Uncle Fred wrote the resolution for the FANHS Board of Trustees and they passed it in 1991 with the first observance nationally in 1992. Our FANHS chapters around the country started commemorating Philippine American History Month activities in October. It just grew from there. Institutions, schools, a lot of universities picked them up libraries city governments, county governments, state governments started picking up the resolution to honor our Filipino American history. We say Filipino American history, not heritage because we are a historical society, number one. But Number two, to recognize the history and the contributions of Filipinos to these United States of America. Not necessarily just Lumpia and dances and food. We are more than Ube. That’s right. And there’s nothing wrong with that. We’re more than that, because Filipino American history is American history as well. And so then in the 2000s as our membership was growing And as our conferences were being more and more attended, a lot of our members in Washington, D. C. wanted to advocate and took up the charge from Uncle Fred, right? Uncle Fred asked them, hey, let’s try to get this through Congress. And it went. For a few years and didn’t necessarily pass as, as a history month until 2009.

So 2009 we had representatives present the bill. We mobilized a lot of our members to call their Congress. People and it went through and then subsequent bills happened in 2011 and other years to officially recognize October as Philippine market history month. Barack Obama was the first White House celebration of Filipino American History Month. That meant a really big deal for us in FANHS that it was being recognized nationwide.

President Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris also issued proclamations resolutions this year. It’s grown as our communities have grown, as our historical society has grown and it has expanded throughout the country and even in the curriculums. So we’re really proud of that.

[00:15:09] Aisa Villarosa: the success would not be possible, but for intergenerational solidarity, right? Almost being hand in hand with generations past and present and food, food is totally political Ate Em. So, so yes, calling, the great Dawn Maboulon, into the space, many Americans, are taught, unfortunately, by sort of the dominant structures that food is not political, but it’s absolutely political, right?

And I appreciate you sharing with the listeners the history behind the history, right? That this is both an accounting of the triumphs, the heartache, the fact that Many Filipinos use the term barkata, and when we look at the genesis of the word barkata, that term, which is almost like a friend that is really family, there’s a spiritual bond there that was born of Spanish enslavement and colonization. So important that we ground the conversation in this.

[00:16:09] Emily Lawsin: Yeah, and I thank you for bringing up my My Kumadre, the late Dr. Dawn Bohulano Mabalon. For the listeners who don’t know, we consider her the queen and really was the foremost Filipino American historian of our generation. She passed away in 2018. Dawn was a incredibly gifted scholar was a very good friend of mine. Dawn was also a food historian, a labor historian a women’s historian but she was also an activist she was a film producer she was a hip hop head she was a baker. the most incredible ube cupcakes you’d ever have. She was multi talented . Every day I think about how blessed we are to have known her, have her research still with us. I think, carries a lot of us who are close to her forward in the work that we do, but it also is continuing to teach younger generations now. You mentioned the intergenerational nature. That’s totally what FANHS is. Dawn and I both came into FANHS as students. I came in as a high school student volunteering in Seattle and Dawn came in to our Los Angeles chapter. She was one of the founding student members of our Los Angeles chapter and then became a trustee and national scholar and was author of several books primarily her book on Little Manila in Stockton. Little Manila is in the heart. Since her death, I think a lot more young folks have mobilized and learned about her great activism to save Little Manila is not only in Stockton, but in other cities and towns all over the country to document Filipino American history through recordings, through music, through art. She’s just inspired a whole, new generation because of the great work that she did.

She wrote the landmark children’s book on Larry Itliong one of the founders of the United Farm Workers Union. It was really the first illustrated children’s book on Filipino American history. Gail Romasanta, our friend from Stockton was her co author and really wanted to thank Gail for Carrying forward Dawn’s vision and publishing that children’s book and her comadre, Dr. Allison Tintanco Cobales from San Francisco State University and Pinay Pinoy Educational Partnerships, created an incredible accompanying curriculum guide. Which a lot of us use at all different levels. The book is supposed to be for like middle school age students, but I assigned it for my college and university students. Because it was such a pathbreaking book. It’s so informative and the accompanying curriculum guide really helps teachers and students, even families, engage with the material more and gives you discussion prompts and ideas as well. It is really an example of a researched children’s book and grassroots effort to spread that knowledge around.

After Dawn died we told Gail the publisher and co author, we’re still going to do the book tour. I had promised Dawn that we would do that. I think it was like 20 cities across the country. It was amazing. It’s really a testament to the intergenerational nature, the grassroots nature of FANHS. We run totally volunteer up until probably next year. Wow. Next year we’ll probably hire our first staff person in 43 years. Because Auntie Dorothy Ligel Cordova has done it as a volunteer executive director.

Oh my gosh.

[00:20:16] Aisa Villarosa: Just a labor of love and also it’s so important to build out the infrastructure so that that is good news.

[00:20:23] Emily Lawsin: Totally labor of love. So if y’all are looking for a really worthy donation place, then that is it. Totally tax deductible.

[00:20:32] Aisa Villarosa: And our listeners. can check out. We’ll have some links related to this episode where folks can support you Ate Em as well as FAHNS. And as you were sharing, I kept thinking, some folks say art is our memory of love. But teaching is also an act of love. As you do as Ate Dawn Allison, so many have done are doing it is an act of love. And yet, Because of the violence of our systems we have book bans, we have attacks on ethnic studies still in 2023. How do you keep yourself nourished?

[00:21:12] Emily Lawsin: Oh, such a good question. We had a penialism. Peniaism is a term that Dr. Allison Tintiaco Cabal has created, wow, 30 years ago now, or maybe less, maybe 25, I’m dating ourselves. She says peniaism equals love and pain and growth. That is so true. I believe in writing as my kind of outlet. Write for two reasons, love and revenge. Because what other reason would you write, right? So that’s like a therapy outlet. To keep myself nourished, I’m really blessed to have a very loving partner and a very loving family. They nourish me. every day, literally feed me when I’m working late. But also with their love and their kindness and their brilliance.

My two daughters are incredibly gifted and brilliant and just really blessed to have them. But also I think when I look at our community. Our Filipino American community specifically and how it’s grown and changed through the years. Auntie Dorothy, when I was in college, was my professor and she used to say that our Filipino American community is built on many different layers.

We have so many different generations that have immigrated over the years. And so every generation builds upon the other, the next generation. It’s all these different layers. And I think that really helped me conceive of What it means to be in community with such a diverse Filipino American population. That education that knowledge has nourished me more than really anything else, because then I could. Always fall back to those teachings that Uncle Fred and Auntie Dorothy gave me. I was very blessed to have grown up on the Filipino Youth Activities Drill Team in Seattle that Uncle Fred and Auntie Dorothy co founded with other families, Filipino American families, as a way to keep Pinoy kids off the streets, right?

It taught us our history and our pride, and gave me confidence in being Filipino, right? Being brown, being different. So that has constantly nourished me. My parents and their memory has nourished me because basically the work that we do, whether it’s paid or not whether it’s art, whether it’s performance, whether it’s history, writing, activism, or working for the man, making the dollar, whatever.

To me, that’s all fueled by the ancestors, and they literally plowed these fields before us, right? My uncles were farm workers. They were migrant farm workers. My mother was one of the first Filipino American women to work in the Alaskan cannery as an alaskera. You hear a lot about the Alaskeros or maybe you don’t, I don’t know.

But she was one of the women and that is really. important to me. It’s important for my children and others to, to know that history. If I remind myself that we’re really doing the work of the ancestors then it’s all worth it. It’s all really worth it.

[00:25:07] Aisa Villarosa: They say we don’t know who all our ancestors are, but they know who we are. What you shared is also similar to Kapua, right? This concept that our identities are shared. So thank you for giving us your time and also just sharing what keeps you running on love in each moment.

[00:25:32] Emily Lawsin: Absolutely. I just wanted to add a big thank you to you. I’m going to play the interviewer because I am the oral historian. I want listeners to know the good work that you’ve done. Since you were a student, a mentor activist yourself, an attorney working with youth and now working in the anti Asian violence movement, it’s really important. In Philippine American History Month, it’s not just about celebration. It is about commemorating the memories of those who’ve been killed. The memories of those who’ve passed I know you know about Joseph Aleto the Filipino American postal worker who was killed by a white supremacist on his work route a mile from my house. I was teaching at California State University, Northridge then, and the students said something incredible when they were organizing around that case.

They said he was not in the wrong place at the wrong time, because people say that, right? When those kind of what they call random acts of violence happen, it wasn’t random at all. He chose to kill Joseph Aletto because he looked like a person of color. He worked for the federal government. So the student at Cal State Northridge said, no, he wasn’t in the wrong place at the wrong time. He was at his place, at his time, doing his job, just doing his job. The killer, the white supremacist, was the wrong person, at the wrong time. Joseph Aletto did not deserve to be killed like that.

After he was killed, his memory was immediately ignored. And it wasn’t until his family, his mother, Lillian, his brother, Ishmael, and his sister in law, Dina, stood up and said, “We will not have this happen to another family. We will not be ignored. ” they started a movement Join Our Struggle, Educate to Prevent Hate.

And still love equality and tolerance and others, which is an acronym for his, the letters in his name. I totally supported that and love the Alato family for their activism to this day. So I want to thank you. For educating others in the work that you do now, you want to tell that because that’s part of Philippine American history.

[00:28:17] Aisa Villarosa: Thank you. And especially given our hard and painful moments right now thinking of. The pain felt by both Students and teachers of ethnic studies to many miles away the pain felt by Palestinians, right? There is a challenge and a duty that we have to both see the humanity in ourselves, but also bridge the shared struggles to humanize when we can because the stakes are too high. So thank you for reminding us of that. It was so beautiful to talk with you today. I hope listeners check out the links on our page and can learn more about Atta Emily Lawson’s work and the work of FAHNS.

[00:29:12] Emily Lawsin: Thank you, Aisa. I appreciate you. Mahal to everybody and Salama. Thank you.

[00:29:20] Miko Lee: Aisa, I’m so glad that you’re also sharing some music with us tonight. Can you tell us about the musician we’re going to be hearing from?

[00:29:28] Aisa Villarosa: Absolutely. I’m honored to introduce my friend and colleague, Mario, a. k. a. Power Struggle, who has been a behemoth in the Bay Area and global music and activism scene for many years. Power Struggle tells the story of The Filipino community, both in the Philippines, as well as connecting the dots to social justice and economic justice in the Bay Area and beyond.

[00:30:00] Miko Lee: Coming up next is Cultural Worker featuring Equipto by Power Struggle.

Welcome back. You are tuned into apex express, a 94.1 KPFA and 89.3 KPF. Be in Berkeley and [email protected]

[00:34:45] Aisa Villarosa: You were listening to Cultural Worker featuring Equipto by the Bay Area’s own Power Struggle.

I am here tonight talking to the incredible Dylan Rodriguez. Dylan, it is a pleasure to have you on the show with us.

[00:35:01] Dylan Rodriguez: I’ve never been introduced that way. Thank you. Thank you for doing that. I decline. I decline all of the superlatives, humbled. I’m very humbled to the conversation. I’m grateful for the invitation.

[00:35:12] Aisa Villarosa: Let me, I’ll try that again. Here is Rabble Rouser Scholar extraordinaire Dylan Rodriguez.

[00:35:18] Dylan Rodriguez: Yeah, troublemaking, troublemaking’s good. Yeah, I’m down for that.

[00:35:22] Aisa Villarosa: Dylan, I have to say most folks tuning in are based on the west coast, but you are gracing us with your presence from the east coast. So thank you.

Thank you for being on late with us tonight. Can you tell the audience a little bit about yourself? Maybe starting with what do you do?

[00:35:41] Dylan Rodriguez: I’m a professor at the University of California, the Riverside campus. This is now my 23rd year there. Despite multiple efforts, they have not been able to get rid of me yet. And I’m very proud to say that my primary vocation extends significantly beyond my day job. I think perhaps the most important part of What I would say I do biographically is that my life work is adjoined to various forms of collaborative attempts at radical political activity, speculative and experimental forms of organizing and community. I’ve been engaged in abolitionist Forms of practice and teaching and scholarship and organizing since the mid to late 90s.

I’m interested in collaborating with people who are down with Black liberation anti colonialism opposition to anti Black racist colonial state. I’ve been involved so many different organizations and movements that I lose track, but I think that’s, in a nutshell, what I’m about.

[00:36:39] Aisa Villarosa: So you’re in Your 23rd year the Michael Jordan year, and thank you for sharing with us. It sounds like you are a world builder Grace Lee Boggs often says that how can we build the future if we’re not visioning it and working toward it. So thank you for everything you’ve been doing and In terms of in the classroom, can you talk a little bit about what you teach?

[00:37:04] Dylan Rodriguez: I teach a variety of different classes that center the archives, the thoughts, the writing, the poetry, the art of radical revolutionary liberationists and anti colonial organizers, thinkers, and scholars. For example, this right now, for example, right now I’m teaching a graduate class in anti Blackness and racial colonial state violence.

And we’re reading a variety of people. I’m interested in, in the whole spectrum. of thought and praxis that is attacking the racist and anti Black and colonial state. I teach another class on the prison industrial complex and that’s a class I’ve been teaching for more than 20 years and I teach it from in a in an unapologetically experimental abolitionist position.

So I’m interested in stoking and supporting whatever forms of collective and collaborative activity are possible to at bare minimum to undermine The premises of this carceral regime that we all live under and I teach a bunch of other things too, but I think the overall trajectory that I’m interested in is some combination of radical autonomy revolutionary trajectory and also just. As I get older, I become less patient. So I’ll say that I feel like a lot of the way I teach all the content what I teach now, whether it’s in a classroom or somewhere else is increasingly militantly accelerationist I think that there is a place and a necessity for accelerating, militant opposition and confrontation with this unsustainable, genocidal, civilizational project that we all differently inhabit. I feel like it’s an obligation to teach and work within an identification of that context.

[00:38:47] Aisa Villarosa: What I heard you say is. You’re less patient and it sounds like it’s because we are running out of time.

[00:38:53] Dylan Rodriguez: Yeah, we are living. I think we’re outta time. I think we’re outta time. I’m unprecedented times. Yes, we’re out of time and mean as we have this conversation and as I’ve been saying to anybody that listen to me, these these last several days. We’re in a moment of an actual unfolding genocide, and I’m not sure, I’m not sure that those who identify themselves as the left, particularly the North American and U. S. left, have an adequate sense of urgency and honesty about what it means to be in this historical moment.

[00:39:26] Aisa Villarosa: I’d love for you to break this down. I wonder if at this moment, there are folks listening who are completely in agreement. There might be some other folks who perhaps are not sure what to think. And some of that, a lot of that is the impacts of colonization itself, right? We are trained to think small culturally, put your head down. You mentioned you teach anti Blackness and as someone who grew up in racially segregated Michigan with a Black and white and Filipino family, people used to joke that we were the United Nations of families. And yet we did not have the words to talk about anti Blackness. We did not. Unpack it in any sort of meaningful way. And we didn’t consider what it meant for our Black family members. So for folks listening who are perhaps new to unpacking anti Blackness, unpacking the genocide in Palestine. Can you connect the dots a little bit?

[00:40:33] Dylan Rodriguez: I can do so in a provisional way. I have no definitive answers for anybody who hears this broadcast or reads this transcript. So let me just start with that. I don’t present myself as having answers really at all. What I have are urgent, ambitious and militant attempts. But let me just say that’s where I’m coming from. I believe in experimentation. I believe in collective, collaborative. militant work that, first of all, identifies the very things you just did. So I want to just, first of all, reflect back to you how important, how courageous it is to just use the terms, right?

To use the terms, to center the terms of anti Blackness, to focus on anti Blackness is so principled and it is also principled it is a principle and it is principled to focus on anti Blackness as a specific way in which to experience and confront and deal with the civilizational project that is so completely foundationally violent.

To name what is happening right now in Palestine by way of the United States and its militarization support of the state of Israel as genocide. That takes some courage on the part of whoever says it, and I think it’s a courage that is emboldened when it’s a collective courage. So what I’ll say about it as a provisional response as a partial response to what you said is that.

I think everything that we do in relation to these dynamics to these forms of violence that are so foundational to the way in which the present historical tense is formed around us, meaning genocide of Palestinians displacement genocide apartheid against Palestinians, and this foundational modern structure of anti Blackness that naming those things, and then identifying how it is that it is not an option to develop it.

It’s principled, political, ideological, spiritual collective relationship, you have to figure out what your relationship is to those dynamics. You have no choice. What I have no patience for are those who would treat these things genocide in Palestine, the global logic of anti Blackness, as if it’s somehow optional.

As if it’s somehow as if it’s somehow elective that it’s a volunteeristic kind of alternative to deal. You have no choice. You have to figure out, articulate, and hopefully you’re doing this in collaboration with other people.

You’ve got to figure out what your position is. And once you do that, things tend to map themselves out because you get pulled in and invited into projects and collective work that actually tends to be really emboldening and beautiful. So I’ll say that like wherever you are, whether it’s northern Southern California, whether it’s I happen to be right now on the East Coast in the state of New Hampshire I live in Southern California. I think identifying those things is the first and most important courageous collective step.

[00:43:18] Aisa Villarosa: And turning a little bit to ethnic studies, which we heard previously from Atta Emily Lawson about the power of ethnic studies and if done right, if taught in a liberatory way, it gives us the answers. It helps us bridge gaps that oppression wrought on us, and some would say that’s dangerous. Can you share what you have experienced as An instructor as a scholar of ethnic studies in your long career,

[00:43:54] Dylan Rodriguez: So first of all, shout out to Dr. Emily Lawson, one of my Thank you. youngest old friends. All respect and all empowerment to everything that she says. So I just I do my best to amplify whatever it is that she’s done and said. So I come out of ethnic studies. I got my Ph. D. In ethnic studies. I’m one of the people who was humbled to be part of, I think, the new kind of the most recent revision and reification the newest chapter of ethnic studies, which people call critical ethnic studies. So I’ve been in, in the ethnic studies project for essentially my whole adult life.

I’m now 49 plus years old, so it’s been for, it’s been a while that I’ve been involved. So ethnic studies, As far as what it does in the world, I’m going to go the opposite direction that some of my colleagues do, and I don’t mean this to contradict them, this to compliment them. I think ethnic studies is productively endangering.

I think it is constructively violent. I think ethnic studies is beautifully displacing. That’s been my experience with it, and what I mean by those things is this. I’m convinced that if one approaches ethnic studies as something more than just an academic curriculum, if one approaches it as a way to reshape how you interpret the world around you, how you understand history, how you understand your relationship, both to history and to other people, that it should shake you to your foundations.

It really should. And the reason I say that is because, for the most part, the ways in which people, especially in North America, are ideologically trained in whatever school systems they experience from the time they enter a language is to assimilate, to accept and to concede to the United States nation building project, which is empire, right?

It’s a continuation of anti Black chattel. It’s all of these things, which we started this conversation with. It’s all those things. So what ethnic studies does is it should shake you to your foundations by way of exposing exactly what it is that you have been. In some ways, literally bred into loyalty to so so when it shakes with your foundations, that’s an endangering feeling.

I’ve had it so many times in the classroom where I can sense it. I can. And sometimes students, the students who are the most, I think audacious will articulate it that way, right? And they will, they’ll sometimes hold it against the teacher, right? Whether it’s me or somebody else. And I’ll say I feel like I’m being attacked, right?

And you know what? I used to be defensive about that, but you know what? In probably the last 15 to 20 years, I tell them, you know what that’s how you should feel. Because what’s happening right now is that you’re experiencing an archive and a history and a way of seeing the world that is it’s forcing you to question Essentially some of the most important assumptions that have shaped your way of identifying who you are on this planet and in the United States and in relation to the United States and the violence of the United States.

You’ve never thought about the United States as a violent genocidal anti Black nation building project. Now that we’re naming that. Yeah, you know you’re feeling a kind of violence through that and ideological violence you feel displaced by that you feel endangered by that.

That’s all right. That’s all right because I’m here with you. You know I’m here with you and we’re all in this. At the same time, and the point is to figure out what’s going to be the right some people will just disavow it and they’ll do their best to fabricate their own return to the point from which they started.

And then a lot of other people will never be able to go back to that same place that is the beauty of what I understand to be the best of ethnic studies is it displaces people from this default loyalty to the United States nation building project it disrupts the kind of default Americanism. That seems to shape the horizon of people’s political, cultural, ideological ambitions, and it says that there’s got to be something on the other side of this that is liberatory, that’s a different way of being in the world.

That’s the best of ethnic studies. And so I do my best to work within that lineage, within that tradition, within that ambition.

[00:48:02] Aisa Villarosa: I am thinking about. Adrienne Marie Brown and folks who say subscribe to the Nap ministry, et cetera. And as we progress generationally, we, in some cases, get a more nuanced vocabulary for times to pause, times to recharge you know, COVID 19 name your thing. Is there room in this struggle knowing that essentially we’re out of time, right? The timer is going off. Can we rest? And how can we find rest in each other?

[00:48:46] Dylan Rodriguez: That’s such a hard one. I’ll be completely vulnerable with the people that are listening, reading, and experiencing my comments right now. I would be a hypocrite to say That I fully ascribe to any regime that is committed to self care, right? I’d be lying. I’d be lying. I feel like I’m mostly committed to trying to engage with whatever forms of possibility radical possibility are available at my best to the point of getting close to exhaustion and then stopping and taking a rest and just asking people to give me a break and people are very just so let me back up the people who I tend to collaborate with nowadays are incredibly generous.

They look out for each other. They give me more of a break than I probably need or deserve. All right, so but I’ll say at the very same time with what is. obsessing me is this kind of humble notion that I want to maximize whatever contribution I can make to advancing some form of a liberation and abolitionist and anti colonial and Black liberation project before I walk off the mortal coil.

That’s it. That’s my contribution. I feel honored to be part of that. I don’t expect to necessarily see the liberation, the revolution, the decolonization in my lifetime, it’s not about that. It’s not that narcissistic. I got over that many years ago. So I’ll say that with all humility with all vulnerability to people here, and I don’t prescribe it.

I’m not saying anybody should be like me. To the contrary. I think the lesson that I’ve learned from a variety of comrades who are much more mature than I am in terms of understanding the limitations of doing work this way and people have exemplified. A version of collective self care that attacks the kind of neoliberal individualized notion of self care that frankly really gets under my skin.

They have taught me what my friends at the what [Big Tree & Martine] and I’ll send you the link so people can check them out. They’re the co founders of Ujima Medics in Chicago. I quote them all the time on this. But they have talked to me more than once about the notion. Of collective and deep responsibility.

So I think I would use the term of deep responsibility, rather than self care I would use the term deep responsibility as a way to understand what it means to be in community with people who will make sure that you take the time that you take the space to recharge and pause that people who will recognize your vulnerability and your exhaustion.

And make sure that you’re able to rest to the point where you will remain a warrior that’s effective in this ongoing struggle. And warrior when I say warrior I mean that all different kind of ways, right? There’s all different kind of warriors. So I think what Martine and Amika talk about is deep responsibility is the one I would really emphasize because I think it’s a notion of collectivity and it means that we’re actually looking out for each other.

And what it means is that we are pushing each other to care. For ourselves and others are caring for us, maybe in a way. That is wiser than we are capable, than what we are capable of doing for ourselves. And I know, and again, with all humility and vulnerability, I feel like that’s what I need from people around me is to be around people who believe in that form of deeper collective responsibility.

I’m probably not capable of it, right? That makes me, I know that makes me a bad abolitionist, everybody, but but others have taught me that’s my limitation. So I feel like that’s where I’m at.

[00:52:10] Aisa Villarosa: You’re winning the. Award for most honest guest star on this show, Dylan.

[00:52:17] Dylan Rodriguez: I have no choice. I have no choice.

[00:52:20] Aisa Villarosa: How can people support

[00:52:21] Dylan Rodriguez: you?

Oh man I don’t need support. I don’t need support from people. I don’t. I don’t. I don’t I feel like there’s so many, there’s so many collective organizations and What I’d rather do is if you wanna get in touch with me, I’m happy to do that. People hit me up.

I’m on social media, like I’m on Instagram and Twitter. Just look me up. Dylan Rodriguez 73 on Instagram. Dylan at Dylan Rodriguez. On Twitter. I guess it’s called X Now. I don’t know, I’m gonna jump off those platforms at some point, but for now I’m still on ’em. Email. You can email me at Dylan Rodriguez, [email protected].

So that’s a cool way to get in touch. So I feel like I’m Profoundly privileged position. Again I get to participate in all different forms of collective work. I have plenty of support. So I don’t want people supporting me. What I want people to do is figure out what kinds of collaborative collective collaborative and collective project around them that are seeking autonomy.

That’s what I want people to do. That’s what I want you to support. I want you to support autonomous projects. For liberation revolutionary struggle. And if it if there’s decolonization there as well autonomous projects that are not dependent on the state that are not dependent on the Democratic Party that are not dependent on nonprofit organizations, non governmental organizations that don’t Rely on public policy reforms.

If there are communities organizations around that are seeking to create autonomous forms of power. That’s what I want people to support. I think that’s what needs to be modeled. That is what is on the other side of this collapsing civilization. Are these forms of autonomy, the sooner that we can begin to participate and experiment and autonomous forms of community that creates autonomous forms of things like justice, freedom, security.

You know what I mean? It’s secure. Health security, food security, education security, recreation security, the security of joy, collective love, all that stuff. The sooner that we can figure out different models to do that there may be an other side to the collapse of the civilization, which could very well happen in the coming days.

I think depending where you are right now, it might be happening now. So that’s what I would ask people to do, would be to support something like that. And if not, instigate and create it.

[00:54:28] Aisa Villarosa: So appreciate that. And earlier… Off the recording, you and I were talking about something doesn’t need to last forever to be successful. There is a molting that is happening now, a shedding, if you will. And so for listeners who are beginning their journey, you’ve made them feel just a little bit less lonely. So thank you for being on the show with us tonight, Dylan. Do you want to close with any final words for the audience?

[00:55:01] Dylan Rodriguez: Yeah first of all, thank you for inviting me. I hope we can do this again sometime soon. This is a beautiful few minutes I shared. I do not take for granted that people are listening to this and taking it to heart. So I think the closing words I would offer to anybody who is interested in being engaged with the historical record to which we are speaking.

I would just ask you if you’re not already involved in some form of collective creative work. Whether it’s something you would call a social movement, whether it’s formal organization or whether it’s something else. I will just ask that everybody here that’s listening to this, if you’re not already involved in something that’s collective that is collaborative and ideally that is radically experimental and willing to look beyond.

The horizons that have been presented to you as the farthest possibility. I want people to speculate and to figure out what is beyond the horizons that have been presented to them as the limit. What is beyond that? And I’m talking to artists. I’m talking to poets, scholars, activists, organizers, whoever is here, people who are incarcerated, everybody who’s here, like there are so many different traditions that we can attach ourselves to all those traditions are collaborative and collective.

So please just be part of a collective. Be part of a collective and for whatever it’s worth reach out to somebody who can help you facilitate joining a collective. That’s why I left you on my contact information, because for whatever it’s worth, if I can play a small role in that, I’m down to do it.

You probably don’t need me. You probably got somebody else in your life that can help you do that. But do something that is collective, collaborative, experimental. That’s my that’s what I would leave with people. Yeah, that’s the last words I would leave with people.

[00:56:38] Aisa Villarosa: Borders are meant to be broken. So thank you, Dylan, for expanding folks vision tonight.

Thank you for inviting me.

[00:56:47] Miko Lee: Thank you so much for joining us. Please check out our website, kpfa.org backslash program, backslash apex express to find out more about the show tonight and to find out how you can take direct action. We thank all of you listeners out there. Keep resisting, keep organizing, keep creating and sharing your visions with the world. Your voices are important.

[00:57:11] Miko Lee: Apex express is produced by me. Miko Lee. Along with Paige Chung, Jalena Keane-Lee, Preeti Mangala Shekar, Anuj Vaida. Kiki Rivera, Swati Rayasam, Nate Tan, Hieu Nguyen and Cheryl Truong tonight’s show is produced by me Miko thank you so much to the team at kpfa for their support have a great Night