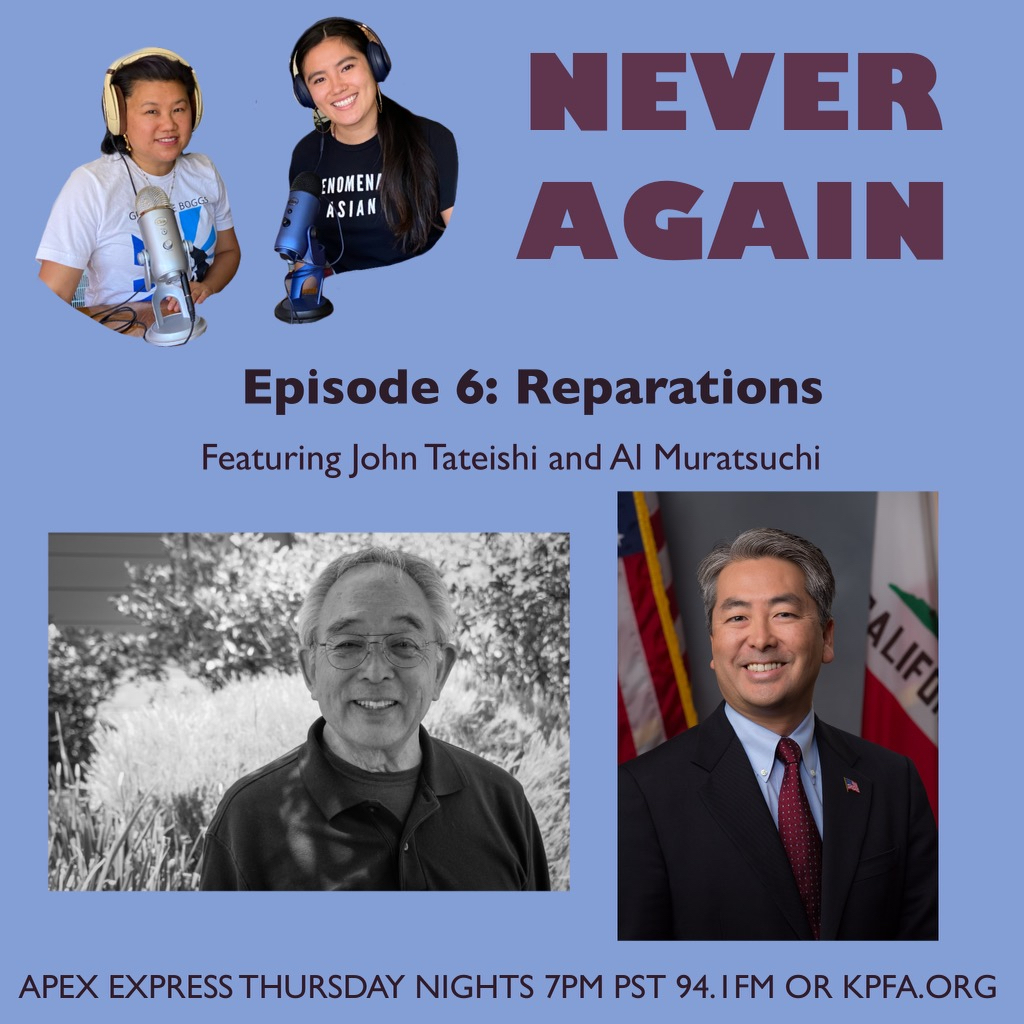

A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists. Tonight Powerleegirls Hosts Miko Lee and Jalena Keane-Lee talk about Reparations and Solidarity with author John Tateishi and California Assemblymember Al Muratsuchi.

A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists. Tonight Powerleegirls Hosts Miko Lee and Jalena Keane-Lee talk about Reparations and Solidarity with author John Tateishi and California Assemblymember Al Muratsuchi.

John Tateishi shares about his book Redress, The Inside story of the Successful Campaign for Japanese American Reparations. We get insight into the work it took to achieve American’s groundbreaking apology and restitution. Assemblymember Al Muratsuchi speaks about successfully leading a bill for California to apologize for the role it played in carrying out policies that discriminated against Japanese Americans before and during World War II.

More info about guest/author John Tateishi

Purchase Redress, The Inside story of the Successful Campaign for Japanese American Reparations here: https://www.asiabookcenter.com/

More info about guest/politician Assemblymember Al Muratsuchi

More about musician featured Miya Masaoka

Redress Show Transcripts

Opening: [00:00:00] Asian Pacific expression unity and cultural coverage, music and calendar revisions influences Asian Pacific Islander. It’s time to get on board the Apex Express. Good evening. You’re tuned in to Apex Express.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:00:18] We’re bringing you an Asian American Pacific Islander view from the Bay and around the world. We are your hosts, Miko Lee and Jalena Keane-lee the powerlee girls, a mother daughter team,

Miko Lee: [00:00:28] Welcome to our series, Never Again, where we will explore stories about the exclusion and detention of Japanese Americans during world war II. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, president Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed executive order 9066, which unjustly called Japanese Americans a threat. Over 120,000 Japanese Americans and Latin Americans were incarcerated for over three years. The majority of the Japanese American detainees were from the West coast where they had excelled and creating robust farmlands. Pressure from the white farm industry was a major factor in pushing forth the racist internment policy.

Jalena Keane-Lee: Tonight, we’re talking about reparations. We speak with author, John Tateishi about his book redress, the inside story of the successful campaign for Japanese American reparations. We get insight into the work it took to achieve America’s groundbreaking apology and restitution. We also speak with California assembly member, Alimera, sushi, who successfully led a bill for the state to apologize for the role it played in carrying out policies that discriminated against Japanese Americans before and during world war II. First up we talk with author John Tateishi.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:01:40] What is your connection with the concentration camps?

John Tateishi: [00:01:44] I was born before war world war two started. I was about two and a half years old. When my family we were in Los Angeles, my family was sent to the earliest of the 10 concentration camps to open Manzanar. My connection to this whole issue is that I grew up in Manzanar, an American concentration camp.

Miko Lee: [00:02:09] Did your family talk with you about why were your in the camps. When did you first become aware of being incarcerated?

John Tateishi: [00:02:17] As children our lives were built around a lot of innocence and our parents really tried to protect us. So they didn’t really talk to us about why we were there. I was six years old when we left Manzanar, to return to Los Angeles. By that time I understood why we were there. In a way a child’s logic would work. I figured out at some point, and this is long before we left Manzanar. I was maybe five when I realized that everyone inside the camp was Japanese. Those who came in and left were always white that they could leave, but we were not allowed to leave. And, seeing these guards with rifles in these towers and the search lights at night, and the fact that we were not allowed to leave Made me understand that we were prisoners, that this was a prison we were in. Essentially this is where my consciousness began. I had no idea what was out there to me that was America outside the perimeter of the fence. And so for me, it was a very strong awareness that being Japanese meant we were there that we were somehow unable to leave and that there was a demarcation of good and bad, safe, and unsafe and the way, as a child, you was, you would establish this kind of right wrong. All of that in my mind, it was very clear that dichotomy existed between Japanese white being in prison and being out there, which I didn’t at that point equate as free. I would see these cars going down the highway in front of the camp on highway 395. ,I realize at one point, all the people in those cars are white. And so there was a kind of movement that could occur for them, but never for us. It had a lot to do with shaping the way I saw the world.

Miko Lee: [00:04:27] Where did your family live after Manzanar?

John Tateishi: [00:04:30] We lived in West Los Angeles, which is an enclave on the West side of LA, right on the border of Santa Monica. We lived there before the war started and we returned to that same place because that was our home. Although we had lost our house and lost everything we had, there was a church there that we belonged to a Methodist church. And so when we returned, when they closed the prisons down and released us, there was a massive migration from the camps into the cities and towns from which we had come. And so we all returned basically to where we lived before the war. And in, in our case, it was West Los Angeles. And we moved into this church into the social hall. And if we thought we were really crammed together in the barracks and the, at Manzanar, it was very tight at in the church after we returned. But, we knew that was going to be a temporary situation. We would live there and then eventually find other places to live. When anyone could raise enough money to move.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:05:42] Did you grow up talking about the concentration camps and your experience there, or was it something that was kept quiet in your family?

John Tateishi: [00:05:48] The interesting generational differences between the Nisei, my parents and my generation, the Sansei was the way in which we reacted to what happened to us. For all of us there was a sense of shame about. Camp is we always used to call it. but as children, we would talk about camp like at the playground or when we’re in school or after school. we grew up with each other in the same neighborhood. So all of us had been at one prison or another. And so we talked all the time about camp, in the way young people ask the question, “Oh, what school do you go to?” Or if you’re working you generally will ask someone, “Oh, what kind of work do you do?” And you identify with what you do or where you’ve been, or where you Mark yourself as part of. For us, the question always, if we met a new kid was “what camp were you in?”

That told us a lot about that person’s experience because. By the time we came out and we were talking we had a sense of which camps where we’re situated in, or had situations that were perhaps controversial or disruptive or certain things happened at certain camps. Manzanar for example, had a riot, which was a huge riot throughout the camp. So we would identify, but we talked about camp all the time. The Nisei on the other hand could not, and would not talk about it at first because you come out of a prison and you don’t go around bragging about, “Oh, I’ve been in San Quentin” and that kind of stuff, you keep it to yourself because it’s a shameful experience. For the Nisei, it was especially that. Because they believe so much in their American citizenship because they were born in this country and they were Americans by birth. They were really proud of their role in this country. Then to suddenly lose all of their rights and get thrown into prison and essentially get labeled as traders to this country. Left the mark on the Nisei. And so as we came out of these prisons, they could not talk about it and they refuse to talk about it after a while. It was an episode that went fairly unnoticed by the general public, because no Japanese American would talk about it in public.

So the word just stayed contained within our community. Our parents didn’t talk to us about camp, what happened and what that was all about, but we talked to each other as children. So we had a kind of catharsis from the experience. We talk because I think we were trying to understand what it all meant and what happened to us. And we were able to resolve a lot of the psychological parts of that experience. Because among us, it was shared. We communicated a lot about our experience during those three years in these prisons, our parents couldn’t do that. even for us, we’d be sitting around like on the playground or during recess and talking about camp experience. If a white kid came over, maybe a good friend of ours, we would stop talking and, they would often ask, “what are you guys talking about?” And we just wouldn’t tell them because to us, it had that same sense of shame. Although we didn’t understand it in the same way our parents said. What we understood that we had been prisoners, that what happened to us was a shameful part of experience.

And so we never shared that, or even talked about it with our non-Japanese American friends. So you know it became this thing for us. Like a sort of psychological survival after the war to talk about camp. So you get my part of the generation born before during the war that could verbalize that whole experience. Then you get a younger part of the Sansei generation born after the war. Mostly in the 1950s who grew up never knowing anything about what happened because they were younger than we were. Often by three, four, five years old, when you’re a kid a year is a big separation, and so as kids, you don’t play with younger kids and the younger kids would try to hang around, but we pushed them aside. So that experience stayed with us, the older part of the Sansei generation. It was a younger part of the Sansei’s who knew nothing about it and started finding out about it when they went to college. Some history professor would just as a footnote, mentioned that, “Oh, and by the way, during the war, Japanese America, were put into these relocation centers for their own protection against these mobs roaming the streets out to kill us.” Which wasn’t true at all.

But that was the government’s rationale or explanation of why they had removed us, and put us into these 10 different places. History professors, even in college, didn’t talk about what happened or the constitutional significance of our experience. And generally added it as a footnote to the discussion, maybe a two week discussion about world war II. And then as a, an added on statement before going on to Korea or whatever else was happening, the cold war, that sort of thing was this, Oh, by the way, comment about our having been in these camps and described as a fairly benign experience for us. It was for the younger, sensei’s a really shocking recognition of something that happened that they knew nothing about and eventually, they would start to learn more about it. Very little, but, they w they learned enough about it, that they really felt a need to talk publicly about that experience. And after the civil rights movement it became an issue.

Miko Lee: [00:12:34] There’s so many interesting things that you said. When the younger generation that were raised in the camps started talking about the camp experience. How did they have those visions about what happened at Manzanar, or crystal city or Minnetonka? Where did you all get an idea of what each camp meant.

John Tateishi: [00:12:52] There was a kind of hierarchy that we created ourselves and keeping in mind that the whole community in West LA was sent to Manzanar. So for us, Manzanar was King of the mountain. We had these troubles in Manzanar so we talked about it in terms of where we were. Japanese Americans living, for example, on the East side, went to different places, different camps. Every now and then one of their families would move into our neighborhood. And so they were talking about a very different experience before and after the war. Japanese Americans who lived in other places and went to what were called assembly centers. Initially, which were the racetracks around Los Angeles. Which had been converted into these temporary camps with, fences around and families, moved into places where animals had been kept, like horse stables and these different facilities with other barracks being built as temporary facilities until the permanent camps were ready. Our family went directly from West LA to Manzanar. Other people in LA went to the assembly centers and then were moved to Manzanar are when the camp was completed. So the experience really varied on where you lived.

There were some people, a few families in West LA for some reason were sent to camp in Arizona and it was called Gila River there was no logic in the way we understood where everyone’s going. What we talked about as we would have these Interchanges of people coming into the area or are meeting other Japanese Americans who had been at other places, we would tell stories. Kids are full of stories because experiences, while they may have been similar, it was like the same story or the same theme with a variation. There was that riot at Manzanar. There were other camps that had different kinds of problems. It was always a kind of comparison of what they experienced versus what we experienced. It wasn’t competitive so much as trying to understand and come to terms of what our different experiences really signified about us as kids. We were all very aware that these were camps only for Japanese Americans. We understood that. A lot of what we would talk about is how someone in someone’s camp and one of the camps Found a way to get under the fence and not as exactly escape, but have an outing outside of the camp. These weren’t prisons where they take role all the time.

We were just detained families lived together and we had our own community within the camp. But we were very restricted on certain things. The main part of which was we could not go outside the fence. Some kids figured out a way, in fact, at Manzanar, you could crawl under the fence and go along a Creek. And the way the guard towers were situated, they wouldn’t see you. Kids found out about that. There were adults who did that because they wanted to go trout fishing. So they went fishing and there was in fact, a fishing club at Manzanar. We’re in a desert area, high desert, and there’s no water nearby except for these creeks that were, that would come down off the mountain. And how in the heck do you form a fishing club? And a concentration camp. The reason was they found a way to sneak out of the camp and go under the wire and and get over to a Creek. they would go through this like a gully. So as kids, we learned how to get out of the camp, but it was always with a sense of risk because we never knew if at some point trying to sneak out to go out and mess around in the desert. If the guard ever saw us, what that would mean, because we knew the guards were serious, that when they threatened us and told us as kids, he tried to go out, I’ll shoot you. I think most of us, I certainly took that seriously. But we talked about those kinds of experiences we had at Manzanar versus what other kids experienced at their camps.

Miko Lee: [00:17:52] Did you all speak with your parents about this?

John Tateishi: [00:17:55] You don’t situation was different than most families because my father was, he was a Kibei. He was born in the United States. That whole part of the Nisei generation of kids born in the United States. My father was born in San Francisco. Families who had the means to do it, sent their children to Japan, for education because their parents felt like my grandfather felt that the education in Japan was far superior than the education kids were getting in California schools. And particularly because schools are segregated. So the Kibei’s were all American born. Kids who were sent to Japan for their education. In my father’s case, he was in Japan through most of his schooling. In fact, he had started university by the time my grandfather had him return to the U S and so having lived as part of a majority part of a society.

There was much more self-confidence sense of themselves, the Kibei. They found it peculiar that the Nisei weren’t more assertive with whites because the experience of the Nisei was very different because there was so much discrimination and limitations on who they could be as citizens that there was, I think unconsciously a sense of being second class citizens among the Nisei were the Kibei really thought that was a bit odd because, they were educated in Japan, some for only a few years, some like my father for a considerable amount of time. And so they came back to the United States with a very self-confidence sense about themselves and their only handicap was, they didn’t speak English very well. In Japan, these only spoke Japanese, but they all had this strong sense of themselves as Americans. So there was that separation between the Nisei and the ki Bay. And my father was a very outspoken Kibei.

He thought what was happening to us as the war started was outrageous and unjust and thought we should resist the orders to report for what the government called an evacuation. His attitude was “the hell with you. We’re Americans, we’re not going to do this.” But ultimately everyone cooperated and went. We had no choice. There was nothing we could do to resist it. Throughout the camp experience, my father was very angry about what was happening and used to speak out at meetings and he was considered a troublemaker, potential troublemaker because he was a leader of the Kibei groups and was very vocal in his rejection of the Army’s treatment of us. In fact, he was sent away from Manzanar to a facility called Moab, which was a high security containment area and was there for a while and then ended up at another similar place in loop Arizona.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:21:36] Was your father a member of the no-no boys?

John Tateishi: [00:21:38] No, my father was not. Which was interesting because most of the Kibei answered yes to the loyalty questionnaires. My father was among them, even at the time that the questionnaire was administered in the camps. He was in the special prison. That’s when the loyalty questionnaire was administered throughout all the camps. He answered yes to 27 and 28, which I always thought was remarkable because he was such an outspoken critic of the injustice. He answered yes to both questions. My mother, on the other hand, she’s a young mother with four kids and my father gets taken away from Manzanar and sent to Moab and the questionnaire comes out. My mother understanding my father’s anger and understanding his criticism of the government, treating us this way. And also the fact that he had grown up in Japan because he had gotten his education there. She assumed he was going to answer no. My mother answered no to the loyalty questionnaire and then found out later he answered. Yes. And so there was this possibility that our family was going to get split up. It was a really long story of how that didn’t happen. But but my father to answer, long answer to a short question, my father talked to us about camp all the time after the war.

And so we had this connection to the camp, both through our conversations with our school friends, the kids that we grew up with and by my parents. My mother mainly answered questions that we asked. My father talked about the injustice and kept saying, it was wrong. And as we were trying to rebuild our lives after the war, he continued to be really outspoken about what the government did to us at these meetings. That would take place in our community in West LA and invariably stuff came up about the war years. My father was out there saying what he thought. For me and my brothers, there was a lot that we remembered because we talk so much about it with ourselves, among ourselves as brothers and with other kids.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:24:14] Thank you so much for sharing that. That’s incredible. I was wondering if we could talk about your book readdress, the inside story of the successful campaign for Japanese American reparations and how that came about .What inspired you to start writing it?

John Tateishi: [00:24:28] Was involved with a regional campaign from almost the moment I joined the JCL and it’s a really interesting story because the Kibei, were really critical of the JACL did not get along with JACL members because there’s such a different psychological or mental state between being a Kibei and a Nisei. The JACL was limited to Nisei membership. They would accept Kibei, but you’d have to be exceptional as a Kibei to want to join the JACL. It was an organization that I grew up. Not necessarily not liking, but feeling very indifferent about. I thought of them as really conservative, but quite honestly, I didn’t know anything about what they were doing as most of the community really didn’t understand the JACL. When in fact it was a very progressive organization. I joined the JACL in 1975 mainly with an interest in this issue they had been talking about called reparations. I got involved immediately in that issue. Then eventually became the chairman of the national committee, whose job it was to try to resolve a lot of these issues that were really difficult. I’d launched this national campaign and guided the JACL through it’s most tumultuous years. Finally, the only thing we had was one bill that was either gonna make it or die. I left the campaign before it finished But I was still engaged in the lobbying because I had been doing all the lobbying for the various bills that we had considered. I was involved in the campaign from the moment it became a public campaign and I was the one who was responsible for all the strategies for the campaign. After I left, after the redress bill was successful and signed by Ronald Reagan into public law a lot of things started happening in the community. At one point, Senator Daniel Inouye started talking to me about recording the history of the campaign. He said that, this was such a remarkable and unique campaign that 50 years from now historians are going to want to write a about how exactly we did this. And you’re the one who needs to write this history.

Jalena Keane-Lee: Wise words from Senator Inoyue who encouraged author John Tateishi to share the story of how Japanese American reparations and redress came to be. We’ll hear more, but first let’s listen to Mia Masoaka Monk’s mood .

SONG

Jalena Keane-Lee: That was Monk’s mood by the great composer and sound artist. Mia Masoaka. You are tuned in to apex express on 94.1 KPFA and 89.3 KPF. Be in Berkeley and [email protected].

Miko Lee: [00:29:40] In the beginning of the ACLU and the NAACP didn’t support redress, right?

John Tateishi: [00:29:47] Yeah, absolutely. They didn’t.

Miko Lee: [00:29:49] And so what brought them around?

John Tateishi: [00:29:52] ACLU was a fast turnaround because they saw the merits of the constitutional issues we were discussing. The NAACP had other issues that were legitimate, but difficult for them. One is that they had been talking for decades about needing to address slavery and the impact of slavery on the lives of black America. And, the civil rights movement was about that. It didn’t quote fix the problem. It was still a problem. And there needed to be a different kind of reckoning about the black experience through the early slaves and to the civil rights movement. And as we started this, and this was codified as a campaign by the JACL in 1970 and as it inched along and started sweeping across the country The NAACP was really interested because they were trying to figure out how to get reparations, but without any success. suddenly here we are a really small group. There were 120,000 of us in world war two. Back in the early seventies, a population of a hundred or 650,000. We were still a tiny part of the population. Yet we were somehow percolating the idea of what this concept was into the public mind and pushing a bill through the Congress. They found that really hard to deal with because they were trying to push their own reparations issue without any success at all. I talked to John Conyers who was the original sponsor of a black reparations bill. Who said to me, this is really difficult because we need to resolve our issue.

He felt that, pushing really hard to support our effort would take away from what he needed and, we could cut whatever deals he wanted, but in the end he felt that in all good conscience, he needed to support the Japanese American redress bill. One of the ideas that we bounced around at different times was, if we were able to succeed and our chances are better because the numbers were simply smaller, the dollar numbers, but if we’re able to succeed, it opens up that door because no one had ever tried this before.

This was a completely unique effort and that. No one believed it could succeed. Nobody, even me, I didn’t think we’d ever get the money bill through not in the very beginning of this campaign. It wasn’t until I saw that our public education campaign was gaining more and more success that I began to think my God it’s possible where we could even get a money bill through. The critical factor for us in all of this was the biggest risk of this whole strategy, which was to have the Nisei testify. But once they saw that this was something more than just the grab for money and that this was not just about somehow revenge, but it had a larger purpose. They started to break down that resistance and and once the dates of the hearings were made public, they were clamoring to be on the witness list. It was a real risk because if the Nisei didn’t react and refuse to testify, There was no way we could win this fight. It needed the Nisei support. One is they were the voice of the experience because those of us who were, Sansei we were all kids, the oldest Sansei was maybe 10 years old at the time of the incarceration. most people would look at that and say, what’s a 10, 10 year old kid now. We needed the Nisei. Besides the fact that they experienced the incarceration in ways that we never did. They understood exactly what was happening. They went through the loyalty questionnaire. They went through volunteering and going off to fight the war or resisting and answering no to the questionnaire. It wasn’t until these public hearings that the Nisei spoke. They were the ones who ultimately convinced the American public that in fact, this was. A gross injustice.

Miko Lee: [00:34:58] Have you. Been working with other leaders from black lives matter or any of the reparations movements that are going on for either indigenous or black communities?

John Tateishi: [00:35:09] I’ve talked with some people in the black reparations movement. I’ve done some zoom talks about my book, and we’ve talked about how there may be some ways in which the Japanese American redress campaign can inform some of the thinking of black reparations

Jalena Keane-Lee: We thank author, John Tateishi for filling us in on his experience with the Japanese American reparations movement. Next let’s listen to bones by Mia Masoaka.

SONG

That was Bones next step Miko speaks with California assembly member Al Muratsuchi about how the state of California is addressing the history of Japanese American concentration camps

Miko Lee: [00:37:52] Welcome Al Muratsuchi, California, assemblyman representing the South Bay area of Los Angeles. I know that you were born in Japan. So can you start by telling us about when you first learned about Japanese American and Japanese Latin American incarceration?

Rep Muratsuchi: [00:38:11] Yes. Really didn’t learn the history of Japanese Americans as well as Japanese, Latin Americans, until I got to Berkeley where I went to college. I started taking ethics studies courses at a UC Berkeley. And that’s when my eyes were open to history that was much more relevant to my personal experience. Learning more about the world war II experiences of Japanese Americans

Miko Lee: [00:38:39] in 2017, you introduced a bill to expand upon the education about the interment and linking it with current civil liberties assaults. I’m wondering if that was influenced by your ethnic studies background?

Rep Muratsuchi: [00:38:53] Definitely. Ever since learning about the history of Japanese Americans and how it fit in with my life experiences. As well as the larger world seeing the similarities between the immigrant experiences of Japanese Americans and comparing that to what the immigrants from Mexico from central America were going through, especially during the Trump administration seeing families being torn apart, being seen children being held in cages. For many Japanese Americans it struck a chord it brought back deep personal scars memories, painful memories of when Japanese Americans who were incarcerated over 120,000 during world war two simply because of their race. And starting with my my consciousness raising from ethnic studies in college and through the civil rights work that I’ve done ever since then. I learn to connect the dots between in this case, what happened to Japanese Americans during of world war II and what we saw happening to Latino immigrants during the Trump administration, as well as many of the ongoing struggles that California and American Muslim communities have faced, especially during the Trump administration.

Miko Lee: [00:40:10] Last year in California, you put forth HR 77. Can you describe this bill to us?

Rep Muratsuchi: [00:40:17] I introduced a house resolution 77 in the California state legislature which was basically an apology from the California legislature to all Americans of Japanese ancestry for the past actions taken by the California legislature that supported the the unjust incarceration of Japanese Americans during WW II. A lot of people, think of California as being, a deep, blue, progressive state in many ways. But I felt that it was important to remind people that California before and during world war II, especially was at the forefront of the attacks, not only against Japanese Americans, but against all Asian Americans. The Hearst newspapers were at the forefront of whipping up the frenzy of the “yellow peril.” Scapegoating immigrants from Asia, not just from Japan, from China and other Asian countries, for taking away the jobs of Americans and all of that anti-Asian hysteria. Then it was whipped up by the media, by political leaders, including California legislators, before and during world war two directly led to the incarceration of over 120,000 Japanese Americans. I felt that it was important for the legislature to acknowledge California’s role and the legislature’s role in the anti immigrant and anti-Asian hysteria.

Miko Lee: [00:41:39] California is the first state to offer this apology. Is that correct?

Rep Muratsuchi: [00:41:44] That’s right. Yeah. While many people may know that in 1988 president Reagan signed the civil liberties act which issued an apology on behalf of the nation for the incarceration of Japanese Americans. To my knowledge, this is the first apology issued by state legislature. I found it was important for the California legislature to be the first, because of it’s sad history in leading much of he anti-immigrant, anti-aging hysteria that led up to world war II.

Miko Lee: [00:42:18] Can you talk a little bit about how the California farm agricultural industry was involved in pushing for the incarceration of Japanese Americans?

Rep Muratsuchi: [00:42:29] Yes. Similar to a lot of the rhetoric that we hear today directed toward immigrants. Starting around the turn of the century, many Japanese immigrants came to California and made a living as farmers as basically a sharecroppers. the first-generation Japanese immigrants were prohibited from owning land. There was the alien land law of 1913 passed by the California legislature, which prohibited Japanese immigrants from owning farms as well as owning homes. A lot of this was in reaction to the farmers in the state of California that felt threatened by these Japanese immigrants. They was taken away their business . It was seen as a competition. They lobbied their state representatives to pass racist laws like theAlien Land Law of 1913.

Miko Lee: [00:43:22] Governor Newsome recently issued an executive order, also apologizing for California’s role in violence, against indigenous Californians and called for this official reconciliation commission. I’m wondering if you can speak about reparations and apology and connections with other movements that are happening right now, like with black lives matter and indigenous rights.

Rep Muratsuchi: [00:43:45] We need to connect the dots see the parallels between the experiences of Japanese Americans during world war II and of course the long and tragic history of the experience of indigenous peoples in state of California, as well as across the country. Now there’s a growing movement. Not just in the black communities across the country, but including the Japanese-Americans growing number of Japanese Americans are calling are supporting this national movement to establish a national commission to examine the impacts of the ongoing legacy of slavery in the African-American experience in the African-American communities across the country. This is in large part driven out of the experience within the Japanese American community, where it was the establishment of a similar federal commission, the commission on wartime relocation and internment of civilians that really started the national dialogue.

It started the national conversation on what exactly happened during world war two. Why did it happen? What can be done to provide reparations and perhaps more importantly to acknowledge the history, learn the lessons of history and to apologize for these injustices that have occurred in our nation’s history.

Miko Lee: [00:45:06] So we’ve talked a bit about the impacts of the Trump administration, which we know have been devastating for people of color in our communities. I’m wondering what changes you see in the Biden administration in terms of dealing with immigrants, kids in cages and the impacts of hate crime against our peoples.

Rep Muratsuchi: [00:45:27] We are hopeful that with the Biden administration, we will take a more progressive approach to immigration policies, very encouraged with President Biden proposing A pathway to citizenship for our undocumented friends. We’re seeing hopeful signs but we know that the challenges continue not only for immigrants, but also for people of color living in California, living in the United States. We know that there’s been a disturbing spike in the number of anti-Asian hate crimes. We’ve seen some high profile incidents recently of people attacking our most vulnerable, our senior citizens who are just going out for a walk, going for shopping in their neighborhoods, in their communities. Just being blindsided for no reason other than hate. We know that during this this pandemic, there’s a lot of people hurting out there. There’s a lot of people that are trying to look for scapegoats for their hardships whether economic or mentally or otherwise. But the challenge continues, whether we’re talking about fighting hate crimes, whether we’re talking about the issues of police brutality of criminal justice reform our challenges continue.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:46:49] What stood out to you from the show tonight?

Miko Lee: [00:46:51] There was so many things I’m thinking about reparations and the impact that it could have in terms of cross solidarity work. I think back to an interview that we did a few months ago, with Lisa DOI from Chicago’s J ACL. She was talking about the reparations that are going on now.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:47:10] Yeah, she was talking about this new cannabis legislation that took the taxes on cannabis and invested that into the black community as a form of reparations, which I thought was really interesting.

Miko Lee: [00:47:19] What I like about Chicago’s bill is that they’re utilizing a new tax. They were able to distribute $25,000 to 16 different black households to use for home repairs, down payments or property. It’s to address red lining and the fact that there’s been housing discrimination against black folks, and it was done using a new tax on pot. It’s not that many people, but it is a start. It’s actually the first monetary reparations that has happened in the United States, specifically for black folks. I really appreciate how the JACL stepped in to help support that. John Tatieshi actually gave advice and feedback on that movement.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:48:06] Yes, he’s quite the legend. It was great to hear those stories from him and his really personal inside look. One story that really stood out to me was just talking about, , it was like to be a child in the camp and to still have this like playful, youthful vibe. And that very much intentionally maintained by their parents, but the story about mans and AR and sneaking out really stood out to me.

Miko Lee: [00:48:32] The entire fishing club was just such a lovely image that just not just the young people, but that the adults too had a fishing club in a desert. It is just so crazy to think about having to be sneaking out under a fence in the desert under guard to go fishing. There’s something crazy and poetic about that.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:48:56] I really want to see what that looked like. Stream..

Miko Lee: [00:48:59] I’m very curious. Manzanar is one of the sites that they do have a visitor center up there now, and they do a pilgrimage. The other thing I thought was really interesting is that in Canada, the Catholic church has actually pledged a hundred million dollars in reparations to descendants of people who were former slaves. So that’s the huge initiative for that church. And they said, they’re going to raise the money and they’ve already set up a foundation. And they’re also starting truth and reconciliation commission, which I think is really powerful. And it’s something we’ve never done in the United States.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:49:40] That’s interesting. I’m personally skeptical of that, but interesting to see how it will unfold and speaking of Canada and also of the, intersectional applications of Japanese American reparations. I think, something that’s been coming up a lot lately in the news is about all of these boarding schools that first nations people were put into and all of the mass graves that have been found at a lot of those sites and just how painful that is and how that’s not unique to Canada that also has. And the United States and we have that shared history. I think there’s certainly significant reparations owed to the indigenous people of this country and Canada and across the world. I think that’s definitely a place where the legislation and the learning from Japanese Americans can be applied to other communities.

Miko Lee: [00:50:26] With that in mind, one of the biggest things that struck me about both interviews was the critical importance of storytelling. John really personalizing it by telling his stories as a kid and connections with Manzanar but then also his disbelief that reparations were even going to happen. He said, I never thought it was going to happen. And then with money attached to it, and the way they’re able to make that happen was by having those Issei, those elders actually step up, overcome their fear and share their stories. I thought that was really powerful. With indigenous folks, we still have people now that have survived the boarding schools. We should be talking about that. There are in the last few years. There are more and more books and stories about that. There’s a couple of great children’s books and I actually just finished reading the education of April Raintree, which was really lovely. So I think that is starting, but, I do feel like that idea about storytelling and hearing first-person narratives of what they went through really personalized it . Remember John telling those stories about how the kids would say, “what camp were you at?” And just share those stories about the camp, but then the elders didn’t say anything. It wasn’t until Congress, that the elders started signing up saying I want to talk about it. Then there was this healing process by them actually talking about it and hearing other folks.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:51:52] That was really beautiful to hear. The intergenerational healing at work was the way he described it was really great. I also think, when it comes to anything that people need reparations because of if it’s, Japanese concentration camps or the boarding schools or slavery, like it has impacted so many generations. I think it also connects to, the children and adults being held in cages at the border right now. These are entire generations are being severely impacted and there’s going to need to be healing for so long to recover from this. Sharing stories is obviously a really important part, but it has to do with a lot of other things too, because a lot of people share their stories about their pain and they don’t always get reparations.

Miko Lee: [00:52:43] That’s right. I’m wondering about other ways that the reparations movement Japanese Americans can help work in solidarity for indigenous and black folks. Chicago is a great example. I’m wondering if are there other ways that people that are interested in this could be more active.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:53:01] Yeah. I think that’s part of the movement to defund police and invest in communities does play into that, and so there’s a lot of different initiatives that can go towards that I just feel like our taxpayer money is spent on so much horrible things that it would make sense to spend some on this.

Miko Lee: [00:53:21] Absolutely. It was very disheartening last week when Biden made these comments to placate folks about the whole diversion of funds from police departments. They have made up language about an increase in crime over COVID so that they should put more money into traditional police forces. It’s very disappointing that Biden didn’t say how wrong that is.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:53:43] They’re using our community to justify that. They’re specifically thinking about attacks on Asian-Americans and using that to justify increasing police budgets. It’s because of all the unity that they saw last summer with people wanting to defund. So I think another big way that reparations can help and there can be intersectional ideas is that talk to our families about this because the news is showing all of these like black faces that are attacking Asian people. When we know that’s not statistically, what has been going on

Miko Lee: [00:54:14] it’s 75% of the harms against API folks against Asian-American folks have been caused by white folks. So that’s statistically, that is the data. It is not the black and brown folks that are shown on the news. That is intentional by the media manipulation by the system to be able to divide and conquer.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:54:41] Yep. Obviously people with legal expertise on exactly how to get reparations, should be giving advice and working in community as they are, as John is of the people that we have been interviewing have been. It’ll be great for that to continue, but even if you don’t have relevant, legal expertise there’s things that you can be doing. Direct reparations are a great place to start. There’s always requests on social media and other places that people needing help with housing needing help with food, all that kind of stuff, and donating to a mutual aid. Your neighborhood mutual aid project can also be a great way to just do some interpersonal on the ground reparations while also supporting like broader pieces of legislation and other things that can help.

Miko Lee: [00:55:21] The other thing that I was really struck by is that our assembly member who is Japanese American, but didn’t experience the interment, learned about it through ethnic studies classes at UC Berkeley. That really illuminated the power and importance of ethnic studies and the importance of it our telling our stories. I also thought to our back to our interview with Laureen Chu one of the many people who fought for ethnic studies, and this is the impact that it’s having somebody taking those classes, somebody’s putting this bill forth and his bill is the first state to be able to apologize to Japanese Americans for the harm that they made in creating these laws and supporting them.

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:56:03] We love to see it. Ethnic studies at work. And even if you aren’t, don’t have actress ethics studies, there’s now so many resources available online and so many great places to learn. And then also so much knowledge can be learned through actually doing and through participating in mutual aid projects and other things like that. So I think, we don’t have to, we should do as much as we can to push the government to reparations, but also we do not need to wait for the government because we’ll be waiting forever. Like the reparations should start immediately. People that are in need in your community. People that are defendants of slavery and mutual aid projects and donate to people that need funds.

Miko Lee: [00:56:41] Yes. One of the ways people can help support indigenous people in their own communities is by supporting the Segora Tay land trust. So if you rent or own a home, you go onto that website and we’ll put a link to it in our show notes, and you can help support the indigenous people in your area for the land that you are living on..

Jalena Keane-Lee: [00:57:02] It’s a land tax to the original, safe guardians and keepers of the land.

Miko Lee: Thank you so much for joining us tonight. There were many complicated backstories that were woven into this interview. For more information, we’ve posted the transcripts from the interview along with a detailed linked glossary in our show notes and are currently working on a curriculum and educators guide, which will premiere this Fall.

Miko Lee: [00:57:26] Keep resisting, keep organizing. Keep creating and sharing your visions with the world. Your voices are important. Apex express is produced by Preti Mangala-Shekar, Tracy Nguyen, Miko Lee, Jalena Keane-Lee and Jessica Antonio. Tonight’s show was produced by your hosts, Miko Lee, and Jalena Keane-Lee thanks to KPFA staff for their support and have a great night.