A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists.

A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists.

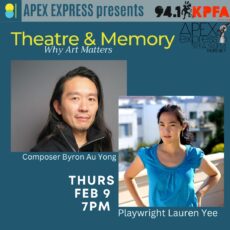

Host Miko Lee talks about Theatre & Memory with Bay Area native artists: composer Byron Au Yong and playwright Lauren Yee. They provide behind the scenes news about their upcoming productions at ACT and Berkeley Rep.

More info on our guests:

Cambodian Rock Band, Berkeley Rep

Transcript: Theatre and Memory or Why Art Matters

[00:00:00] Miko Lee: Good evening and welcome to APEX Express. I’m your host, Miko Lee, and tonight we’re talking about theater and memory or why art matters. So many artists grapple with this concept of memory and how each of us has a different story to share. And tonight we get to hear from two bay area locals, a playwright, and a composer, each share a bit about their creative process and why art matters to them.

I have the pleasure of speaking with composer, Byron Au Yong who had been creating music for the Headlands, which opens this weekend at act. And with playwright Lauren Yee who’s musical Cambodian rock band comes back home to Berkeley rep at the end of the month. First off. Let’s take a listen to one of Byron Al Yong’s compositions called know your rights. This is part of the trilogy of the Activists Songbook. This multi-lingual rap, give steps to know what to do when ice officers come to your door.

song

That was know your rights performed by Jason Chu with lyrics by Aaron Jeffries and composed by my guest, Byron Au Yong. Welcome, Byron Au Yong to Apex Express. We’re so happy to hear from you.

[00:04:11] Byron Au Yong: Thanks, Miko. It’s so great to be here.

[00:04:13] Miko Lee: I wanna talk to you about a couple of things. First and foremost, you have the Headlands that is opening up at ACT really soon. Tell me about who your people are and where you come from.

[00:04:27] Byron Au Yong: Sure. So my grandparents, both maternal and paternal, left China in the late thirties and they both immigrated to the Philippines. And so both my parents were born to Philippines in different areas. And so I come from a family of refugees who then settled into Philippines and my parents were not the first in their family.

They were actually both the fourth and they left and immigrated to the United States when the United States opened up immigration in post 1965. So they were part of that wave. And then I was born in Pittsburgh. They, they were actually introduced here in Seattle. And I was born in Pittsburgh because my dad was in school there.

And then they moved back to Seattle. So I’m from Seattle and in 2016 I moved to San Francisco.

[00:05:17] Miko Lee: Thank you. So you are a composer. Have you always played music and have you always been attuned to audio? Tell me about how you got started as a composer.

[00:05:28] Byron Au Yong: Sure. As a kid my parents divorced when I was age seven and I was an only child up until age 16. My mom worked. In the evenings. And my dad wasn’t in the household and so I had a lot of time to myself and I would sing a lot to myself. And then my next door neighbor was a piano teacher, and so I started to play the piano at age nine, and then at age 11 I started to write stuff down. And yeah, so I’ve been doing music for a bit.

[00:05:59] Miko Lee: So music has always been a part of your life, essentially. It’s been your playmate since you were young.

[00:06:04] Byron Au Yong: Yes, absolutely

[00:06:05] Miko Lee: Love that. So tell us about the Headlands that’s gonna be opening at ACT pretty soon.

[00:06:11] Byron Au Yong: Yeah so The Headlands is a play by Christopher Chen, who you may know is playwright, who is born and raised and continues to live in San Francisco. And it’s his love letter to San Francisco. It’s a San Francisco noir play. It’s a whodunit play. It’s a play about a main character who’s trying to figure out who he is after the death of his dad. Which causes him to wonder who he is and where he is from.

I’m doing original music for the show, this is gonna be an American Conservatory Theater, and Pam McKinnon, who’s the artistic director, will be stage directing this production as well. I actually met Chris Chen in 2013 when I had a show called Stuck Elevator that was at ACT. And I’ve been really fascinated with his work as a playwright for a while, and so I was thrilled when ACT invited me to join the creative team to work on music.

Miko Lee: Oh, fun. Okay. I wanna talk to you about Stuck Elevator next, but first let’s stick with the headlines.This is a play that’s about memory and storytelling. I’m wondering if there is a story that has framed your creative process.

Byron Au Yong: Yeah. Thinking about this show as a memory play, and, memory as something, we go back in our memories to try and figure stuff out, which is very much what this play is. And also to claim and to. figure out if something from our memory was recalled maybe in completely. And so the main character is, piecing together fragments of his memory to figure out who he is in the present. And considering this I actually went back to music. I composed when I was still a teenager.

I actually dropped outta school and was working a lot. I think I realized early on that I was indeed, I wanted to dedicate myself to being an artist and was very concerned about how I would make a living as an artist in the United States. And so I thought I’ll figure out how to make money away from the music.

And so I had a lot of jobs and I was trying to write music, but, I was in a sad place, and so I never finished anything. I have a bunch of fragments from this time. But on Memorial Day I woke up and, it was sunny in Seattle and so I said, I’m gonna finish a piece of music today.

And that became part of a project in mine where every Memorial Day I finish a piece of music and it’s a solo piano piece that I finish. And so, going back in my personal history, I found one of these Memorial Day pieces and thought, oh, this actually works.

Because it’s a bit awkward and it doesn’t resolve, and I remember who I was back then, but it’s also me piecing together things and so I used that as the foundation for the music, for The Headlands, which is a different thing.

If you didn’t know that was my source material, that’s in some ways irrelevant. But that’s my personal connection in thinking about music for this. And of course I’ve also done a lot of research on film noir. A lot of noir films were set in San Francisco. And and the music is awesome, amazing of this genre. And, it’s mysterious it is a certain urban Americana music. And so I include those elements as well.

[00:09:36] Miko Lee: Thank you. That’s so interesting that you have a Memorial Day ritual to create a piece of music. I’m wondering if, aside from the Headlands, have you used the Memorial Day Music in other pieces you’ve created?

[00:09:48] Byron Au Yong: No this is the first time.

[00:09:51] Miko Lee: Wow. Yeah. That’s great.

[00:09:53] Byron Au Yong: I think Miko is because, it’s a private thing for me. I think the other thing too is as you mentioned, music was my friend growing up. The piano was. Definitely one of my best friends.

And so solo piano pieces for me are, it’s where you can have an audience of one. And one of the things that helped me, when I was not in school was. Playing through a lot of different other solo piano pieces. And so part of these Memorial Day pieces too are that they’re meant to be simple enough that they could be sight read.

And so if, if there’s a musician who you know, is in a similar state of, oh, I’m not able to really do anything, but I want to be with music. I can sight read through, these different Memorial Day pieces.

[00:10:38] Miko Lee: And do you have them set in a specific part of your house or where, how, where do you keep your Memorial Day projects and when do you open them up to look at them?

[00:10:48] Byron Au Yong: Oh yeah. They’re handwritten in a folder. None of the things so special.

[00:10:54] Miko Lee: What was it that inspired you to go back and look at them for the headlands?

[00:10:58] Byron Au Yong: Oh, you know what it is there are, be, because I know you, you also create stuff too in your memory of your catalog.I’m wondering if you have. If you have works that, that you remember that you made and then tho those works may remind you of a certain mood you were in or a certain room or and so I think they’re musical things from certain or, things I was experimenting with for these Memorial Day. Said, I’m like, oh, I remember this. Let me go back to the folder where I collect this stuff every year and look through it. And I think that parallels actually the headlands and what the main character is doing because he recalls, and what’s so cool about the production is we go into the same scene, but there’s like a clue that’s been revealed. And so we as an audience get to revisit the scene again. And there’s a different interpretation of what was happening in the scene. And so what might have been like a scene between Henry’s parents, Lena and George, which he thought, oh, this is how it was when I was a kid, when I was 10 years old.

Thinking about it, remembering it, but now with this new information, this is how I’m gonna interpret the scene. And so I think similarly with, music from my past, these Memorial Day pieces, I’m like, oh, this is what I was interested in working on. But now as a older composer, I’m like, ah, and I can do this with this material.

[00:12:26] Miko Lee: I love that. And I also really appreciate that this play about memory you pulled from your Memorial Day pieces, that it goes with this whole flow of just re-envisioning things with your own frame and based on where you’re at in any given time.

[00:12:42] Byron Au Yong: Totally.

[00:12:43] Miko Lee: I know that the show was created 2020, is that right? Yes. Is that when, first? Yeah,

Byron Au Yong: I think it’s right before the pandemic.

Miko Lee: Yeah. And you’ve had several different directors, and now in a way you both are coming home to San Francisco and artistic director, Pam McKinnon is directing it. I wonder if you have thoughts about some of the difference approaches that these directors have brought to the process.

[00:13:06] Byron Au Yong: Oh, yeah. And, miko, this is the first time I’m working on the headlands. And so when it was at Lincoln Center, there was a different creative team.

[00:13:12] Miko Lee: Oh, so the music, you’re just creating the music for this version of the show.

[00:13:16] Byron Au Yong: Yes, correct. Wow. And it is a new production because that Lincoln Center was in a stage called LCT 3, which is a smaller venue. Whereas this is gonna be in a Toni Rembe theater, which is, on Geary. It’s a 1100 seat theater. And the set is quite fabulous and large . And what’s also great is, aside from Johnny, all the cast is local. And like it will have the feel of a San Francisco production because many of us live here, have lived here and know these places that are referenced in the show.

[00:13:51] Miko Lee: Thanks for that clarification. So that’s really different to go from a small house at Lincoln Center to the big house at a c t Yes. With local folks with, your local music. That brings a very different approach to it. I’m excited to see it. That sounds really interesting. And now I wanna go back to talk about Stuck Elevator, which I was so delighted to learn about. Which was your first piece That was at ACT what, back in 2013? So tell our audience first about where Stuck Elevator came from and then tell what it’s about.

[00:14:23] Byron Au Yong: Sure. So stuck elevator. So I was living in New York in 2005 and there were some there were some images of like photos in the newspaper, initially it was local news because it was a Chinese delivery man who was missing. And most of the delivery people at the time, they carry cash, they won’t go to the police. And there, there had been a string of muggings and then one was actually beaten to death. And so it was local news that this guy was missing.

And then a few days later, and in New York Times, there was a big article because he was found in an elevator in the Bronx and he had been trapped in his elevator which had become stuck. And he was trapped for 81 hours, which that’s like over three days. And so it made international news. And then when I read the article and learned more about him, there were many parallels like where he was from in China, which is Fujan Province, which is where my grandparents left that he was paying a debt to human smugglers to be in the United States.

And different things that I thought, wow, if my grandparents hadn’t left I wonder if, I would be the one who was, paying to be smuggled here rather than paying for grad school. And so I became quite fascinated with them. And then also, realized at the time, in 2005, this is like YouTube was just starting, and so all like the Asian American YouTube stars, they weren’t as prominent in the news.

And, BTS wasn’t around then. So for me to see an Asian male. In the US media there was always this feeling of oh why is this Asian male in the news? And then realized, oh, it’s actually part of a larger story about being trapped in America about family obligation, about labor, about fear of, in his specific case because he’s an undocumented immigrant, fear of deportation. So there were many issues that, that I thought were broader than the specific story. And so I thought, this would be a great opera slash musical. So that’s what it became at

[00:16:23] Miko Lee: you, you basically read a story and said, whoa, what is this? I feel this is so wild. And then created it into an opera. Yes. Also, it just resonated with me so much as a person who has been trapped in elevators, in broken elevators six different times, . Oh my goodness. Yes. I’m like, wow. And his story, that many hours, that has to be like a record.

Byron Au Yong: Right? Nobody else has been trapped that long. Yeah. It’s a record.

Miko Lee: So you created this piece, it premiered at ACT? Yes. Did you ever connect with the guy that was stuck in the elevator?

[00:16:59] Byron Au Yong: No. So the New York Times did something which is actually not cool. They they revealed his immigration status and that at the time I’m not sure if it’s still the case,but at the time, you’re not allowed to reveal people’s immigration status. Especially, in such a public way. And so what was cool was that the AALEDF, which is the Asian American Legal Education and Defense Fund, they the volunteer attorneys there step forward to represent Ming Kuang Chen and his case and ensure that he had legal representation so he would not be deported. The thing is, he was suffering from PTSD and there was also another case at the time it was a different un undocumented immigrant case that AALEDF was representing that had a bit more visibility and so he actually didn’t want to be so much into public eye, and so he went back into hiding. And so while I didn’t meet him specifically, I met his translator. I met other people at AALEDF met with other people who were related to the stories that he was a part of. So for example, used to be an organization, which I think they’ve changed their name, but they were the Fujanese Restaurant Workers Association.

Most of the undocumented immigrants who worked in restaurants at the time are from Fujan Province. Also, Asian Pacific American Studies at New York University. Is a mix o f people who were working in restaurants as well as people, scholars who were studying this issue.

[00:18:46] Miko Lee: Can you describe a little bit about Stuck Elevator for folks that haven’t seen it? Sure. How did you conceive of this piece, that song?

[00:18:53] Byron Au Yong: Yeah so it’s a thru sung piece about a guy who’s trapped in America. He’s a Chinese food delivery man, and he’s, delivering food in the Bronx. And what I think is You know what I didn’t realize when I started it. And then I realized working on it was the thing about being stuck in the elevator is, especially for so long, is that you and I don’t know if this is your case, Miko it’s so fascinating to hear you’ve been trapped six different times.

There’s the initial shock and initial oh my gosh, I have to get out. And then there’s this. Maybe not resignation but there’s this, okay. Okay. I’m gonna be here so now what? Now what I’m going to do and the time actually, especially for someone who works so much delivering food and sending money back home to his wife and son in China and his family is that he actually is not working, right?

And so he has time to consider what his life has been like in New York for the past, the two years he’s been there. And to consider the choices he’s made as well as to remember his family who are back in China. And part of this too is you’re not awake the entire time. Sometimes you go to sleep, and so in his sleep he dreams. He has hallucinations. He has nightmares. And this is where the music theater opera really starts to confront and navigate through the various issues of being trapped in America.

[00:20:22] Miko Lee: Any chance this will come into production, somewhere?

[00:20:26] Byron Au Yong: Yeah, hopefully, we were just at Nashville Opera last week, two weeks ago.

[00:20:30] Miko Lee: Oh, fun.

[00:20:31] Byron Au Yong: so Nashville Opera. So the lead Julius Ahn who was in ACT’s production is an opera singer. And and he had told the artistic director of Nashville Opera about this project years ago. And John Hoomes, who’s the artistic director there had remembered it. Last year John Hoomes reached out to me and said, you know, I think it’s the time for to be an operatic premiere of Stuck Elevator. And so we had an amazing run there.

[00:20:58] Miko Lee: Great. Wow. I look forward to seeing that too somewhere soon. Yes. I also wanted to chat with you about this last week, a lot of things have been happening in our A P I community with these mass shootings that have been just so painful. Yes. And I know that you worked on a piece that was called The Activist Songbook. Are you, can you talk a little bit about that process and the Know Your Rights project?

[00:21:23] Byron Au Yong: Yeah, absolutely. And I’m gonna back up because so Activist Song Book is actually the third in a trilogy of which Stuck Elevator is the first, and related to the recent tragedies that have happened in Half Moon Bay and also in Monterey Park.

The second in the trilogy is it’s called the Ones. It was originally called Trigger, and it also has the name Belonging. And I can go through why it has so many different names, but the first in the trilogy was Stuck Elevator, and it was prompted by me again, seeing an Asian male in the US media.

So the second actually all three are from seeing Asian males in the US media. And the second one was an incident that happened in 2007 where a creative writing major shot 49 people killing 32, and then himself at Virginia Tech. And and when this happened I realized, oh shoot Stuck elevator’s part of a trilogy. I have to figure out how to do this show called Trigger or what was called Trigger. And then realized of the different layers in a trilogy. Yes. There’s this initial thing about Asian men in the US media, but then there’s this other thing about ways out of oppression. And so with Stuck Elevator, the way out of oppression is through the main character’s imagination, right? His dreams, his what ifs, right? The possibilities and the different choices he can make with the second one, what me and the creative team realized is that, the way out of oppression is that the creative writing major who you may remember was a Korean American he was so isolated at Virginia Tech and the tragedy of him being able to purchase firearms and then kill so many people, including himself in working on it, I was like, I need to understand, but it’s not this story I necessarily want to put on stage.

And so what it became is it became a story, and this is also the national conversation changed around mass violence in America. The conversation became less about the perpetrator and more about the victims. And so it became a choral work for community performers. So rather than a music theater opera, like Stuck Elevator, it’s a music theater forum with local singers. And this was actually performed at Virginia Tech during the 10 year memorial of the tragedy. And this one I did eight site visits to Virginia Tech and met with people including the chief of police of Blacksburg. First responder to director of threat assessment to family members whose children were lost. A child of, teachers were also killed that day to counselors who were there to Nikki Giovanni, who was one of the faculty members. So yeah so many people. But this one, the second one, the way out of oppression is from isolation into community, into belonging.

And Virginia Tech Administration said we could not call the work trigger. And so the work there was called (Be)longing with the be in parentheses. And now we’ve done a new revision called The Ones partially influenced by the writer, one of his teachers was June Jordan who was at UC Berkeley. And she has a phrase, we are the ones we’ve been waiting for. And so the ones which is a 2019 revision, the show, what it does is Act three youth takeover, right? It’s about coming of age and an age of guns, and the youth have become activists because they have no choice because they are being shot in places of learning, and so Parkland in Chicago and other places have been influential in this work. And then the third in the trilogy is Activist Songbook. And for this one we went back to an earlier asian male who was in the US media, and that was Vincent Chin who you may know was murdered 40 years ago.

And so activist song book is to counteract hate and energize movements. And it’s a collection of different songs that is even further away from musical theater opera production in that the rally component of the songs can be taught within 10 minutes to a group of people outdoors to be used right away. And that one, the way out of repression is through organizing.

[00:25:49] Miko Lee: Well, Byron Au Young, thank you so much for sharing with us about all the different projects you’ve been working on. We’ll put a link in the show notes to the headlands that folks can see at a c t. Tell our audience how else they can find out more about you and your life as a composer and more about your work.

[00:26:05] Byron Au Yong: Sure. I have a website. It’s my name.com or b y r o n a u y o n g.com.

[00:26:12] Miko Lee: Thank you so much for spending so much time with me.

[00:26:14] Byron Au Yong: Of course.

[00:26:15] Miko Lee: You are tuned into apex express on 94.1, KPFA an 89.3 K P F B in Berkeley and [email protected]. We’re going to hear one more piece by composer, Byron Al young called This is the Beginning, which was prompted by Lilly and Vincent chin and inspired by Helen Zia and other organizers.

song

That was, This is the Beginning by Byron Au Yong and Aaron Jeffrey’s. Featuring Christine Toi Johnson on voice and Tobias Wong on voice and guitar. This is a beginning is prompted by organizing in response to the racially motivated murder of Vincent Chin in Detroit. This hate crime was a turning point for Asian American solidarity in the fight for federal civil rights.

Lily chin Vincent’s mom refused to let her son’s death be invisible. Next up, I have the chance to speak with playwright Lauren Yee who’s musical Cambodian rock band. Returns to Berkeley rep where it first got its workshop and it will be there from February 25th through April 2nd. And here’s a teaser from Cambodian rock band by Lauren Yee. Take a listen to seek CLO.

song

Miko Lee: Welcome Lauren Yee to Apex express.

[00:34:35] Lauren Yee: Thank you so much, Miko.

[00:34:37] Miko Lee: We’re so happy to have you a local Bay Area person. Award-winning playwright. Coming back to town at Berkeley Rep with your show, Cambodian Rock Band. Yay. Tell us about the show.

[00:34:51] Lauren Yee: Yes so Cambodian Rock Band. Is actually a piece that has some of its like earliest development roots in the Bay Area and also like specifically at Berkeley Rep. Getting to bring the show to Berkeley rep really feels like some sort of poetic justice. In addition to the fact, that it’s like my old stomping grounds. . Essentially Cambodian rock Band started in 2015, or at least the writing of it. It actually started, if I’m being honest much earlier than that. I think it was about 2010 2011. I was down in San Diego in grad school and one of my friends was just like dying to go see this band play at a music festival. She was like, I saw this band play. They’re amazing. You should totally come.

And I was like, sure. And I don’t know if you’ve ever had this experience, but it’s like, going somewhere, hearing a band, and even before you know anything about them or their story, you just fall in love. You fall like head over heels in love and you say, oh my God who are these people? And I wanna know everything about them.

And that band was Dengue Fever. Which is amazing. You fell

in love with the band first. Yep. Before the play.

Yes. And it was the band Dengue Fever which is an LA band. And their front woman Choni Mall is Cambodian American and she leads this sound that I think started in covers of Cambodian oldies from that golden age of rock for them, and has over time morphed into Dengue Fever’s own original sound.

Like we’re nowadays, they’re coming out with an album soon, their own original songs. But I fell in love with Dengue Fever and I was like, oh, okay, who are these people inspired by? And I just went down that rabbit hole of learning about this whole musical history that I never knew about.

My own background is Chinese American. I’m not Cambodian American. And so a lot of kids who grew up in the public school system, I did not get basically any education about Cambodian history and America’s role in seeding the elements that led to the Khmer Rouge’s takeover the country, and the ensuing genocide.

[00:37:12] Miko Lee: So you first fell in love with the band and then you went down an artist rabbit hole. We love those artist rabbit holes. Yes. And then what was your inspiration for the play itself? The musical?

[00:37:22] Lauren Yee: Yeah so I fell in love with the music and I was like, there is something here because you had all these musicians in Cambodia who like, when 1975 hit and the communists took over the country there was just a time when like the country was a hostile place for artists where artists were specifically targeted among other groups.

And so much of Cambodia’s musicians and its musical history, was snuffed out, and I was like, there is a story here, that I find deeply compelling. And for a long time I didn’t know how to tell that story because there’s just so much in it. And then came 2015 where two things happened.

One was that I was commissioned by a theater in Orange County called South Coast Rep, and they invited me to come down to their theater and just do research in the community for two weeks on anything you want. So I was like, I wanna look at malls, I wanna look at the video game culture down there, all kinds of things.

And one of the things that I was interested in and just bubbled to the surface was the Cambodian American community, which is not in Orange County proper, but in, situated largely in Long Beach, right next door. And it just so happened that while I was there, There were just a lot of Cambodian American music related events that were going on.

So the second annual Cambodian Music Festival, the Cambodia Town Fundraiser, Dengue Fever, was playing a gig in Long Beach. Like all these things were happening, that intersected me, with the Kamai or Cambodian community in Long Beach. And the other thing that happened coming out of that trip is that I started beginning to write the seeds of the play.

And I did a very early workshop of it up at Seattle Rap. And I’m the sort of playwright. probably like writes and brings in collaborators like actors and a director sooner than a lot of other people. Most people probably wait until they have a first draft that they’re comfortable with, whereas I’m like, I have 20 pages and I think if I go up and get some collaborators, I think I can generate the rest of it.

So I went up to Seattle with kind of my, 20 or 30 pages and we brought in some actors. And that workshop had an actor named Joe No in it, and I knew Joe from previous work I’d done in Seattle. But during our first rehearsal when we were just like chatting he said to me like, this is my story.

And I was like, oh, it’s a story that calls out to me too. Thank you. And he was like no. You don’t understand. Like, So my parents were born in Battambang Cambodia. They were survivors of the Khmer Rouge. I feel deeply connected to this material. And that conversation sparked.

a very long relationship, between me and Joe and this play. That I, I think of him as like the soul, of this play. He became just like an integral part. And in the South coast rep production and in subsequent productions he’s kind of been like our lead. He is Chum, and it’s a role that I think is like perfectly suited for who he is as a human being and what his like essence is. And also he plays electric guitar which I think influenced things a lot because initially it was a play about music, right? It wasn’t a musical, it was just people like talking about a music scene that they loved.

And as I went along and found like the perfect people for these roles it was like, Joe plays electric guitar. It would be crazy not to have him try to play a little electric guitar in the show. And that kind of began that, the evolution of this play into a piece where music is not only talked about, but is an integral part of the show. You know that it’s become a show that has a live band. The actors play the instruments. They play about a dozen songs. And it’s a mix of Dengue, half Dengue Fever songs, half mostly Cambodian oldies.

It’s kind of been an incredible journey and I could not have imagined what that journey would be, it’s hard to replicate.

[00:41:53] Miko Lee: I love that. So has Joe been in every production you’ve done of the show so far?

[00:41:57] Lauren Yee: So he hasn’t been able to be in everyone. There were two productions happening at the same time, and so he could only be in one place at one time. But I bet you he would’ve tried to be in two places at once. But he’s basically been in almost every production. And the production that he’s in currently running at the Alley Theater in Houston is is like the production, the original production directed by Chay Yew.

[00:42:24] Miko Lee: Wow. And was it difficult to cast all actors that were also musicians?

[00:42:30] Lauren Yee: In some ways there there’s I think if you were starting from scratch and you like open your window and you’re like, where could I find some actors? I think it would be tough. But I just kept running into kind of like crazy happenstance where I would find a person and I wasn’t even thinking about them musically.

And they’d be like, yeah, like I’ve played bass, for 15 years. and I could kind of do drums, right? That what was remarkable is that there were all these Asian American actors who were like known as actors. But then once you like, dig down into their biographies, you’re like, Hey, I see like you’ve actually played drums for X number of years, or, Hey, I see that you play like guitar and bass.

Miko Lee: Tell me more about that.

Lauren Yee: So it’s almost like finding all these stealth musicians and like helping them dust the instruments off and being like, Hey, come back here. Fun. And so it’s just been, it’s just been like a joy.

[00:43:27] Miko Lee: Oh, that’s so great. I know the play is about music and also about memory, and I’m wondering if there’s a story that has framed your creative process that stands out to you.

[00:43:39] Lauren Yee: I don’t know if it’s one specific memory, but I find that just a lot of my stories I think they deal with family. I think they deal with parents and their grown children trying to reconnect with each other, trying to overcome family secrets and generational struggles. I would say I have a great relationship with my father.

But I think, in every parent and child relationship, one thing that I’m fascinated by are these attempts to get to know someone, like especially your own parent, even when you know them well, and especially when you know them well. That kind of is able to penetrate that barrier that sometimes you hit in generations, right?

That there’s a wall that your parents put up. Or that there’s this impossibility of knowing who your parents were before you had them because they had a whole life. And you only know this like tiny bit of it. And I think I’m just like fascinated by that. I’m fascinated by the impact of time. I’m fascinated by extraordinary circumstances and the ordinary people who lived through those times.

And I think for a large part, even though Cambodian rock band features a family whose lived experience is different from my own. I think there’s a lot of my own relationship with my father that I put into that relationship. This desire to know your parent better, this desire to know them even as they’re trying to protect you. So yeah.

[00:45:06] Miko Lee: What do your parents think about your work?

[00:45:10] Lauren Yee: I think my parents are incredibly supportive, but like different in the way that one might think because my parents aren’t arts people they of course like enjoy a story or enjoy a show, but they’re not people who are like, I have a subscription to this theater, or I’m gonna go to this museum opening. and so their intersection with the arts, I feel like has been out of a sense of like love for me. Their ways of supporting me early on when like I was interested in theater and trying to figure out a way to go about it, like in high school when I was trying to like, put on a show with my friends and they were like in the back folding the programs or like building, the door to the set. And hauling away, all the furniture, so we could bring it to the theater. So like my parents have been supportive, but in a very, like nuts and bolts kind of way.

Miko Lee: That’s so sweet and that’s so important. When I was doing the theater, my mom would come to every single show.

Lauren Yee: Just Oh, bless that is, bless her.

[00:46:14] Miko Lee: Ridiculous commitment. Yeah. I don’t that for my kids, like every show. I wanna back up a little bit cuz we’re talking about family. Can you tell me who are your people and where do you come from?

[00:46:27] Lauren Yee: Ooh. That’s such a great question. I think there are like many ways of answering that. When I think of home, I think of San Francisco, I live in New York now. But my whole youth, I grew up in San Francisco. My parents were both born there. My grandmother was born and raised there, one of my grandfathers was, born more like up the Delta and the other side of my family, my grandparents came from Toisan China. So on one hand, my family’s from like that Pearl River Delta part of China. And at various times, like made a break for the United States. I think starting in the 1870s and spanning into the early 20th century you know, so we’ve been here for a while.

And another way of thinking about it is we’re all very, I think, suffused in our family’s history in San Francisco. It’s hard for me to go to a Chinese restaurant with my family without somebody from our table knowing somebody else in the restaurant, like inevitable.

And it’s something that never happens to me. I don’t think it’s ever happened to me when living in New York. Yeah. And I think And that’s fun. That’s fun. I love that. Yeah. Yeah. And I think b eing able to be Chinese American. Growing up in San Francisco, it’s different than other, Asian Americans living in other parts of the country.

Like in a strange way, it allows you to like be more of whoever you wanna be, right? When you’re like not the only one. That it allows you to like, potentially choose a different path and not have to worry about. I don’t know, just like carrying that load.

[00:48:01] Miko Lee: That is so interesting. Do you mean because there’s safety, because you’re around so many other Chinese Americans, Asian Americans, that you can bring forth a greater sense of your individuality?

[00:48:13] Lauren Yee: Yeah, I think so, like I went to Lowell High School where, you know, two thirds of the class is Asian American. There’s just such a wide range of what an Asian American student at Lowell looks like. And what we’re interested in and how our weird obsessions manifest so I think I just felt more freedom in differentiating myself cuz I like theater and I like storytelling.

[00:48:36] Miko Lee: That’s really interesting. Thanks so much for sharing that. I’m wondering, because Cambodian rock band is partially about when the communists took over Cambodia. If, when you were growing up as a multi-generational Chinese American, did you hear very much about communism and the impact on China?

[00:48:57] Lauren Yee: I did not. And possibly it was swirling around. And I was too young to really understand the impacts. But when I look back on it, a lot of my plays, Cambodian Rock Band included, have to do with the intersection of Communism and American culture. Like another play I have called The Great Leap which was at ACT in San Francisco, also dealt with American culture like basketball, intersecting in communist China in the 1970s and then the 1980s.

And like, honestly, in retrospect, the effects of communism were all around me growing up in San Francisco in the nineties. That the kids that I went to school with, like in elementary school, came there in various waves, but a lot of them pushed from Asia because of the influences of communism that you had of a wave of kids who came over. In the wake of the fall of the Soviet Union, you had kids who came preempting, the Hong Kong handover back to China. You had kids, who came to San Francisco in the wake of the fall of the Vietnam War. So there were like all these, political movements the effects of war that were like shaping the people around me. And I didn’t realize it until like very much later.

[00:50:19] Miko Lee: Oh, that’s so interesting. Thank you so much. By the way. I really loved the Great Leap. It was such an interesting thank you way of really talking about some deep issues, but through such an American sport like basketball I enjoyed that so much. So thank you so much for sharing about your San Francisco influence. I’m curious because you’ve been writing TV now limited series like Pachinko and also congrats on writing the musical for Wrinkle In Time. Amazing. Thank you.

[00:50:49] Lauren Yee: That is a book that I loved and just shook me, I forget what grade I was in, but I was probably like, 10 or 11 or something. So I think the fact that I get to interface and get to dig into such an iconic work as Wrinkle in Time, blows my mind.

[00:51:05] Miko Lee: That is going to be so exciting. I’m really looking forward to that. Yeah. Yeah. But my question was really about you working on Pachinko and these other series, how different is playwriting to screen versus TV writing?

[00:51:17] Lauren Yee: Yeah. I think in a way like the work that I did on Pachinko, for instance, like I was on the writing staff, that’s a role where you’re like supporting the creator of the show, which in this instance is Sue Hugh, who is just an incredible mind. And she had like kind of this vision for what she wanted to do with the adaptation of Pachinko. And, you know, you, as a writer on staff you’re really helping to support that.

So I think your role is a little bit different when you’re brought on staff for tv that you’re helping to birth the thing along and contribute your part. Whereas when you’re a playwright like the piece remains with you, and you just have I think a greater sense of control over what happens to it.

[00:52:00] Miko Lee: What surprised you in your creative process while you were working on this play, this musical?

[00:52:08] Lauren Yee: I think the thing that I realized when I was writing Cambodian Rock Band is that in order for the play to really click together is that joy has to be at the center of it. That Cambodian rock band is a piece about art and artists and family surviving really horrific events. And in order to tell that story, you need to fall in love with the music.

You need to understand why these people might have risked their lives. For art, you need to understand why art matters. And I think a feature of my work is finding the light in dark places that there is a lot, in the play that is heavy. There are points where it is surprisingly and shockingly funny and that there are moments of just incredible heart in places like you probably won’t be expecting. And I think that’s been a big lesson of developing this piece.

[00:53:14] Miko Lee: Lauren Yee thank you so much for talking with me and sharing about Cambodian Rock Band and your artistic process. I know it’s gonna be running at Berkeley rep February 25th through April 2nd. Where else is it running for folks that might not live in the Bay?

[00:53:30] Lauren Yee: Yeah, so if you live in the Bay Area, or if you want just see it again, which is totally fine. Lots of people see it again. This same production is going to travel to arena stage in DC over the summer in the fall it’ll be at Fifth Avenue and Act Theater up in Seattle, and then at the very beginning of 2024 it will be at Center Theater Group.

[00:53:54] Miko Lee: Thank you so much for chatting with me today. I really appreciate you and your work out there in the world.

[00:54:00] Lauren Yee: Thank you, Miko.

[00:54:02] Miko Lee: That was playwright Lauren Yee. And I’m going to play you out, hearing one song from Dengue Fever, which is in Cambodian rock band. This is Uku.

song

[00:56:55] Miko Lee: Thank you so much for joining us. Please check out our website, kpfa.org backslash program, backslash apex express to find out more about the show tonight and to find out how you can take direct action. We thank all of you listeners out there. Keep resisting, keep organizing, keep creating and sharing your visions with the world. Your voices are important. Apex express is produced by Miko Lee Jalena Keane-Lee and Paige Chung and special editing by Swati Rayasam. Thank you so much to the KPFA staff for their support have a great night.