A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists.

A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists.

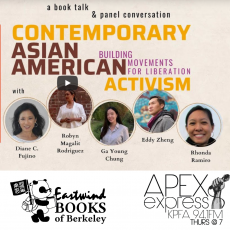

EastWind Books in conversation around “Contemporary Asian American Activism – Building Movements for Liberation,” featuring Dr. Robyn Magalit Rodriguez, Dr. Diane Fujino, Eddy Zheng, Rhonda Ramiro and Ga Young Chung.

Show Transcripts – Movements For Liberation

[00:00:00] Swati Rayasam: Good evening, everyone. You’re listening to APEX Express Thursday nights at 7:00 PM. My name is Swati Rayasam and I’m the special editor for this episode. Tonight, we’re featuring a recent conversation from Berkeley bookseller and movement home, Eastwind Books about the anthology, “Contemporary Asian American Activism: Building Movements for Liberation” edited by activist scholars, Diane Fujino and Robyn Rodriguez.

The conversation moderated by Harvey Dong and Jamie Chen features Diane and Robyn as well as contributors, Eddy Zheng, Ga Young Chung and Rhonda Ramiro. This recording has kind of a rocky start, dropping you in right after the introductions, but sit tight. I guarantee you’ll enjoy it. Here’s Diane.

[00:01:18] Diane Fujino: We thought an anthology would be a way to get this going beyond what’s visible on the internet. And the other part of it is that we really believe in relational leadership. So we wanted to bring everybody together, not just to contribute singular chapters, but to be in dialogue.

And the book centers around many things, but I’ll focus in on four questions. So one is the question of how we actually create change. And here we were looking at not just doing one off events, the work of activists, which are very important, but the work of organizers, those who were building across the long haul, who are looking to build transformative justice, campaigns, movements, really difficult work.

And so we’re trying to center organizing knowledge and we subtitled our book “Building Movements for Liberation.” The second thing that we were looking at is how does Asian American activism build across generations? So we were looking at intergeneration ality and we make the claim that current day Asian American activism can’t be understood without its impact, being rooted in the Asian American movement of 50 years ago. And so we have people like Pam Tau Lee who has done incredible work in the radical Asian American movement and groups like I Wor Kuen and also let out in the people of color movement for what now we think about as environmental justice.

Which also centers anti-racism. Three, we were looking at what kinds of critiques we need, when we think about Praxis, the unity of theory and practice. What kinds of practice, what kind of critiques represent Asian-American activism. Though it’s widespread and though it’s heterogeneous, we really see through lines as fighting structural white supremacy, racial capitalism, and imperialism.

And we wanted that to be known about Asian American activism. And the fourth was a question of how we lead. What kind of organizing models we use. And for us in the Asian-American movement of 50 years ago, it really rested in collective leadership. And as I said, relational leadership. In the book are 12 chapters that cut across diverse ethnic backgrounds that are more California-based, but national as well, that include community organizers as well as activist scholars.

Chapters, such as Angelica Cabande’s looking at resisting displacements in San Francisco and building community in the south of market area. May Fu who is looking at political education happening outside the academy in our communities in Nepalese, Vietnamese, and Southeast Asian communities and New York City, Providence, in Southern California and Karen Umemoto, who was looking at restorative model justice models in Hawaii that rested on native Hawaiian or Kānaka Maoli epistemology.

I’m going to turn next to my chapter on the New York Taxi Workers Alliance. Really incredible organization that’s doing major organizing right as we speak.

They formed in the 1990s, they formed as a lease drivers coalition, the first workers coalition of the coalition of CAAV the Coalition Against anti-Asian Violence, which itself emerged out of the struggles around the Vincent Chin case. And they organized in 1998, a historic one day strike. of 12,000 Taxi workers in New York City. And more recently, they intervened in this neo liberal economy, which is creating this gig economy, which creates only part-time work, that rests on austerity. And when Uber and Lyft drivers flooded the New York driver market rather than separating their work,

Or seeing them as competition, they organized together in the model of the International Workers of the World, that wobbly model of organizing everybody within the same industry. And in doing so, they were able to make significant wins such as getting app- based drivers recognized as employees entitled to certain rights rather than independent contractors.

And in this moment of COVID, they organized tremendously. They talk about taxi drivers as frontline workers who are ambassadors for New York. Who after immigration, they’re picking up international travelers in New York City airports, and yet didn’t have protection. And so they found that 62 taxi workers died in the first three months of COVID. 10,000 taxi drivers contacted them and they did a lot of services to get out information to taxi drivers about housing subsidies, unemployment, and other kinds of things that were really important. And so their work is both labor organizing, but it also spans. All of this and the majority of their workers are South Asian taxi cab drivers, but they’re also organizing in multilingual ways doing just really incredible work.

I’ll stop there and turn it to the next person.

[00:06:43] Eddy Zheng: Happy new breath, everyone. My name is Eddie Zheng. I’m the president and founder of the New Breath Foundation. And it’s definitely a privilege and honor for me to share this space with so many wonderful, and amazing, scholars and activists.

You know, the New Breath Foundation started out from just the fact of the inequity in distribution of resources, in the institution of philanthropy. And when we look at some of the reports being done over the years to the Asian Americans in the name of philanthropy and other sources, we understood that only 0.2% less of those resources, going to marginalized Asian American Pacific Islander community.

And that’s definitely unacceptable. So the New Breath Foundation started from that, value of addressing the inequity. We offer hope and healing and new beginnings for Asian American and Pacific Islander immigrants and refugees. People who are impacted by incarceration, deportation, and survivors of violence.

We wanted to do is to mobilize the resources, to build power capacity infrastructures, for our community and my chapter in this book of, contemporary, Asian, American activism, really looking at the connection of, intergenerational trauma and looking at how mass incarceration and deportation and United States foreign policy impact the API community, really focusing on how, when we are connecting to our history and culture, we’re able to really learn to address the systemic issues that plague all of our communities. And through that process how elders and students can activate to support people who are incarcerated who wanted to learn their culture and history who wanted to create a space for people to achieve their mental freedom and how the administration within the prison industrial complex is punishing those people who are advocating for their basic rights and then also the right to understand where they came from and how they got here.

So in that space, it really documents the movement Asian Prisoner Support Committee and how it is using lived experience of those who are directly impacted to create systemic changes. So I’m grateful, to be able to be a contributor to this chapter and definitely want to talk more. And with that, I’ll just pass it on to my next colleague.

[00:09:35] Ga Young Chung: Hi everyone. I’m Ga Young Chung, assistant professor in Asian-American studies at UC Davis and also a proud board member. And NAKASEC, it has been my great honor to be a part of this amazing research and activist project. And as I appreciate Diane, Robyn and also Eastwind books and the University of Washington press for helping us sharing this chapters with our larger community. In my chapter, I argue how education allowed the undocumented Korean activists to be uniquely positioned, to challenge depictions of themselves as a quote, unquote deserving or disposable, the two dominant narratives framing undocumented immigration.

Their aspiration for education was at first shaped by the pressure to prove their citizen worthiness, to conformity to the existing system. But at the same time, education also became a way for them to fight for justice for everyone, for instance, their liminal and precarious living experiences. Coupled with persistent racialization in the United States, motivated them to create radical spaces for racial dialogue, through multiracial, intergenerational, and intersectional solidarity with other minoritized groups.

So in my chapter, I argue that ultimately young, undocumented Korean immigrants are helping us to create a new vision of Asian-American activism and inspire us reimagine the world we want to live in, in an era of continued US imperialism and on even globalization. My chapter draws on my multi-sited and community-based participatory research from 2013 to 2020.

I conducted this research in LA, Chicago, New York, and Annandale Virginia working closely with Korean-American organizations, including the NAKASEC HANA center, Lincoln center and Korean business center. By working, cooking, and living together with young undocumented Korean activists, I was able to gain a deeper understanding about their life experiences.

Although I was called as a doctoral student from Illinois at the beginning of my research. At some point I became more often called a quote-unquote Korean, Korean sister, a supporter of undocumented Koreans and later a fellow activist. My chapter was structured, analyzed and written with the hope that their challenges or stories will become more visible.

In spite of all the emotional challenges of looking back on the painful moments and struggles they had experienced, my research collaborators, my research participants chose to join my research because they believed that the voices of undocumented Korean, undocumented Asian immigrants should be recorded and heard in public.

I believe and hope that my participation in today’s talk event can be a part of that effort to make their struggles in beautiful contributors, to our radical movement, to be more heard and recognized in public.

[00:13:06] Rhonda Ramiro: Hello. Thanks everybody. I’m so honored to be here with you all to speak on the chapter of this book contributed by BAYAN USA. BAYAN USA was the first overseas chapter of the Philippine based Bagong Alyansang Makabayan or new patriotic Alliance, a nationwide multi-sectoral Alliance of over 1000 grassroots peoples organizations in the Philippines fighting for national and social liberation.

Jessica Antonio, who is our propaganda officer and was the principal author of the chapter, without whom it wouldn’t have been written, isn’t able to join us today. She’s on maternity leave, but shout out to Jess. Our chapter presents a view into Filipino radical activism in the us in the 21st century with the particular focus on why and how.

Filipino activists in the US play an integral role in educating, organizing, and mobilizing their local communities to contribute, to advancing the national liberation movement of the country. So our chapter begins by taking a look at why this organizing is necessary in the first place. We established that the Philippines may be considered an independent country in name, but in reality, we still have this neo-colonial relationship with the US meaning that everything from our economy to our culture to political life is subsumed to the interest of the US and particularly US imperialism.

We also still suffer from the problem of a semi-feudal economy, which keeps the majority of the country’s people in poverty. Because of these conditions, Filipinos have been forced out of our Homeland and at present our community numbers at least 4 million strong and growing in the US the largest concentration of Filipinos outside the Philippines.

Our chapter goes on to describe how Filipinos residing in the US are driven to connect their history, their culture, and Homeland through community organizing and educational exposure trips to the Philippines with the most oppressed sectors of Philippine society, particularly peasants workers and indigenous people.

In the chapter, you’ll get to read interviews with Filipino activists in the diaspora who describe how their deep connection to the Homeland developed through activism. For example, some of the people interviewed were born in the Philippines and migrated to the US they became politicized through investigation into their own family migration story.

Pretty common story of leading the Homeland in order to find work abroad in order to survive. They met BAYAN USA or one of our member organizations who were organizing on issues of immigrant rights. As one interviewee said, quote, “I saw that they were doing work in the community while also providing comprehensive political education, learning about forced migration and imperialism contextualized my own life in a way I’d never been able to articulate before. Their analysis provided also landed on a concrete way to take action, to continue serving the people.”

Other people interviewed in the chapter were involved in political issues based in the US and then got introduced to our organizations. Another person interviewed in the book said, quote,” I was getting more politicized by seeing the Standing Rock and Black Lives Matter movements. I saw Anakbayan was the only Filipino organization really standing in solidarity. Then I learned about our own struggle and it confirmed all the feelings I felt growing up here in the states. It made me feel the connection to home that I’ve been longing for.”

Our chapter ends with a description of how BAYAN USA’s exposure programs are essential in teaching young activists, whether they’re born in the US or born in the Philippines, about the concrete conditions of Philippine society, that have driven so many to migrate around the world. So these trips have become an essential way that activists get a chance to understand these connect conditions firsthand.

More importantly, they get to talk to people, people who live, day in and day out under these conditions, people who want their stories to be told around the world so that they will no longer be hidden from the outside world and that so more people will care and take action to change these conditions.

These interviews feature stories from the front lines, and I’ll end with one last quote, which I think really exemplifies those stories, which are just calling out to be heard and the stories which inspire so much of the activism in our community. So this, story, is quoted, by a member of the women’s organization, Gabriela, Seattle, quote,” there was a woman I met whose brother and nephew was just killed by the armed forces of the Philippines as they were farming. I remember she was explaining to us what they did to them, and she put her wrists together and showed us how they shot them and bound their hands with the abacá they were farming. I have that image burned into my memory, the tears in her eyes, her hands raised up wrist to wrist. She was looking straight into my eyes. She just wanted her story to be told.”

So overall, our chapter describes a radical Filipino activism by sharing the stories of Filipino activists who have found this sense of purpose and responsibility and organizing communities in the US and connecting their local issues to national and an international level, and participating in the movement for national democracy in the Philippines.

[00:18:27] Robyn Rodriguez: My name is Robin Rodriguez and I am a co-editor with Dr. Diane Fujino, who was also my professor now colleague, co-editor of the anthology, and I helped to bring the folks together that, contributed to the book also help to co-write the introduction.

But I also have two sole author contributions to the book that I am going to speak to a little bit now, and then a little bit later, but one of the things I just wanted to say is, I’ve actually been a community organizer much, much longer than I’ve been a professor. I started organizing, in the eighties, in the late eighties as a high school student.

But more recently where I live in the greater Sacramento region. I’m really proud to have been part of the founding of what’s now called the Asian-American Liberation Network. We were, formed during the pandemic and officially launched just last week as an official nonprofit organization.

So very, very pleased to have been part of that. I think though, probably my best contribution as an organizer is frankly having been mother to Amado Khaya Canham Rodriguez, who I will also talk a little bit about later. I want to talk about the chapter that I wrote on my activism.

So the title of my chapter was drawing from Tupac Shakur and it was “Pete Wilson trying to see us all broke: Asian-American across racial student activism in the 1990s, California.” I mean, Tupac really was able to articulate, I think so many of our experiences of growing up in California and actually for a very long time, I’d really wanted to write, I still want to write that book, the entire book on Asian-American activism in the 1990s and 2000s. I’ll get to that, but for now, what I wanted to be able to do, for at least this book was at least start that process of really thinking about the significance of what we contributed as organizers in the 1990s.

So I really decided to reflect primarily on my student activism. And the bulk of my chapter really focuses on the few years I was at UC Santa Barbara. I had transferred to UC Santa Barbara in 1993, kind of hit the ground running and running as an organizer. And, you know, part of why I wanted to focus on student organizing in particular really has a lot to do with intergenerational knowledge that I received from Filipino, anti martial law activists.

I had met these anti-martial law activists already after I had graduated from UC Santa Barbara. But I remember one of the things that they would really emphasize with me and a generation of folks, is the importance of organizing as students.

There’s a distinctiveness about student organizing and it was so important. They would always remind us that the anti-martial law movement really could trace its start to the First Quarter Storm, which is a movement led by students. They would share these writings with me and so many of my other kind of contemporaries by Philippine writers, but also other third world revolutionaries of earlier generations who always theorized about the distinctiveness of the role of students and bringing about a social change.

So I think that all of that had helped me to realize that we were doing something really critical and vital, and we were organizing as students at UC Santa Barbara. There are two key lessons and reflecting from our organizing on campus in the 1990s that I try to convey in the chapter.

And one is that one of the most powerful things about being a student organizer is that your job quite simply is to study. So vital that actually, when you’re a student, your primary responsibility is to study. And I think there’s really no other time in your life.

No other time in your life, when you can engage in full-time study to engage ideas collectively, whether it’s in the classroom or outside of the classroom. And I think that’s one of the really important ways that students can contribute to movement building is simply by studying. And again, whether that happens in the context of the classroom or outside of it, that you have this period of your life when that is kind of your role, that can be so important to social movement work. Another major important contribution that student movements have made or that students make to social movements is the mere kind of sociality of college life. The fact that you’re collectively gathered in one place in classrooms and living situations, that really is what accounts for so much of the ways that students have been able to topple dictators, like in the Philippines or in so many other places around the world really, confront state and all of the ways that it causes violence to our communities. Students are able to mobilize in a way that is not always true for many people because of the way that you’re living together, you’re working together, in college classrooms. And so those are some of the lessons that I wanted to share it with all of you, but of course it go in to much more detail in the book, something, that I hope that just even this brief overview of the chapter, will invite you to consider the unique ways you can contribute to social movement work as a student, because history has shown us that you can, and history will show us that you will.

So thank you.

[00:23:44] Harvey Dong: Thank you, Robyn. We have a set of questions. And after that we’ll take questions from the audience. just bouncing off of what Robyn stated about how social movements, because of the particular nature of students and campus and community and the collectivity that’s built social movements are influenced by what happens on campus and then it spills out into the community.

So the first question I have is to Eddy who was actually influenced by students when you were incarcerated through the passing on of Asian American studies and ethnic studies. And then off of that, you became an activist, but also in prison, you face reprisals for being part of a group that led prisoners’ demands for ethnic studies.

And you went through the solitary confinement for that. What helped you persevere, even though you had to face, repercussions and how did you see the result of this experience, how did you go beyond the reprisals, to build your commitment and, connected with that is also what helped you develop your critical thinking skills, from this process?

You use the term Chi (C-H-I) culture, history and identity. How does that all work? Okay. But in other words, how did you get started?

[00:25:13] Eddy Zheng: Thank you very much Harvey man, where do I start? Right. I mean, not to put you, on the pedestal Harvey it’s because of you and the elders like you who lay your lives down and stood up and advocate right in 1968 or prior to 1968 and 19 68, 69 to now and continue to, mentor students or mentor people in the community.

And so for me, in the invisibility of Asian-American Pacific Islander especially many of the Southeast Asian Pacific Islander folks is already a shame, in the prison industrial complex, where its driven by profit off of people’s back. Right? So when we look in at the 13th amendment of the United States constitution, legalizing indentured servitude is still legal, right?

Like when I say legalize it’s still allowed then, the only way to be able to have a better understanding of that, legalization, forced enslavement. We have to look at education, right? And how the failure of education created that school to prison, to deportation pipeline. And that’s why I’m always talking about the importance of tapping into the Chi. And the Chi I’m talking about. It’s not just the breath and the life force and sustaining our lives, but really it’s focused on cultural history and identity in the sense of how do we invest in ethnic studies, Asian American studies, right? And women’s studies and global studies as a part of the lineage that was fought and earned through many of the activists who came before us to allow us to have that opportunity.

So within the prison system, because we are racially segregated and because we are continued to being treated, even in the prison system as the minority. Within minorities. And that minority within minority is based on the fact that in the larger scale, the AAPI population is still a very small percentage.

When we look at the older representation, the Black and brown and indigenous community, in the prison industrial complex. So we became the minority of the minorities, but yet within that, we are the model minorities. And so from that, we know education, especially culturally competent education, it’s not afforded to the API folks. Therefore, it was out of sheer, one, individual will by that wanting to invest in your learning, or it has to do with the people from the outside who inspire, encourage people who have been isolated from a society to be able to learn. And so, as a result of that, for me and two of my friends who actually were punished by being in solitary confinement, was because we were AAPIs, and because we’re wanting to challenge the administration, in this, practice of dehumanizing people and forbidding people from advocating for what they want. And so in that sense we were able to come together to follow our hearts, you know, and what what’s the right thing to do for us to gain this mental freedom that we so much were hungry for in this space.

But ultimately we came together to really looking at how important it is to develop the critical thinking education. And how I have developed is people like many of the students that you have as a matter of fact Jeanie Lo who used to work at Eastwind, and many of the other students from Berkeley who came in really to demonstrate to us how young people are also following the footsteps of the elders to advocate and maintain the rights of having Asian American studies as a core curriculum. And so when I talking about tapping into the Chi it’s really not only talking about our own culture, history and identity, but really how learn about other people’s cultures, culture, history, identity, so we can better humanize each other. And so from that end, we were able to, get the support, not only from the activist that students out here, but you know, Yuri Kochiyama, our elder who really brought people together and created the Asian Prisoner Support Committee. And from there, we can see that through our advocacy, how Asian Prisoner Support Committee became a movement to really advocate for the currently and formerly incarcerated, and then also create spaces for more opportunities to, for people to really address the intergenerational trauma, through ethnic studies.

So therefore ROOTS was created and co-founded by many of the impacted individuals who are serving time in San Quentin State Prison. So the acronym for ROOTS is “Restoring Our Original True Selves.” So APSC was able to go back into the prison system to create curriculums that model after ethnic studies to seek to address how US foreign policy, how the immigration and refugee histories and stories has created those harm for many of the harmed people to hurt other people. So in that space, we’re able to not only develop leadership skills, we were able to try and create spaces beyond prison. So once they were able to participate in those studies, they will understand that they have value attached prior to when they committed a crime or when were they inflicted harm. And so in that process alone, they were able to really find healing. And then find spaces for taking responsibility for the actions and then to transform themselves. So they can find a space where they can be a contributing member of society.

So hence when you asked the question how has that kind of created an impact? It’s that lineage of all the activists and the people that stood up and who’s made sacrifices continued by this generation and hopefully with this anthology many, of the future generation will be able to look at and learn from all the activism that’s happened within the API community.

And so I just want to close out by saying that since then, APSC has expanded into an unanticipated movement but it became national international because they are supporting people who are impacted by incarceration, deportation that were deported to the Philippines to Vietnam, to Cambodia, and which people are still fighting against this deportation right now through separation of family, as a result of the United States policies domestically and internationally. And so that’s the Routes to re-entry” and New Breath Foundation , as a foundation is because of the movement that started right in 2002 when Asian Prisoner Support Committee was formed. So with that, I’ll just close my thought right there and appreciate that question Harvey.

[00:32:22] Swati Rayasam: You are tuned in to APEX express. At 94.1 KPFA and 89.3 KPFB in Berkeley and online at kpfa.org.

Now back to the Q and a with Eastwind books.

[00:32:39] Harvey Dong: A question for Diane, your article “drivers on the front lines, the New York Taxiworkers Alliance, neo-liberalism in the global pandemic” and interview with Javeed Tariq. One question that I had was, what is the significance of looking into the work of the New York Taxiworkers Alliance for understanding future directions of Asian-American activism? Because a lot of the writings about Asian American activism, seems to not be a big focus on working class and labor type issues. So I was just wondering if, yourself doing this interview and writing it, reflecting on it. Do you think that Asian American studies today is not going deep enough into the issues of class and the class solidarity? And how does that tie into Asian American studies?

[00:33:38] Diane Fujino: Thank you, Harvey. I think that this is a crucial question, right? In fact, the New York Taxiworkers Alliance split from CAAV precisely over some of these issues. I mean, they get along well, they they’re connected. It’s not that there was an antagonistic split, but that they wanted to form their own organization that wasn’t primarily focused on anti-Asian violence, which CAAV formed around, which was so important, given the vulnerabilities of taxiworkers to constant threats and violence. but they wanted to form a workers organization and they wanted to form a workers organization with workers in the leadership. And I think that we have so much to learn from them. I was listening to Robyn talking about how one of the important things about student organizing is that people are in the same space together. And I was thinking, Robyn, what does it mean to be in COVID? Right. But I was also thinking about labor organizing and how, one of the things that at least the older model was we’re in the same space, we’re in the same factories, we’re in the same offices and that provides us with opportunities to learn, to organize, to build social relationships that become important for the organizing, but the taxiworkers don’t have that space. There’s a mobility to the way taxi workers do things. And there’s also that linguistic challenge. I think people talk about multicultural organizing as being different cause people have different cultures and values and misunderstandings, but when you don’t even speak the same language, and one of the things that Javaid Tariq talked about was how, when two taxi drivers lined up at a red light, so this means they don’t have a lot of time, but that don’t talk to the person from your same background, talk to somebody from a different background.

So that was something that they were consciously trying to do. And the organizing and the mobilizing have to be quick and nimble. The majority of the workers, as I said are South Asian Pakistan, Bangladesh from India. And it’s not like there’s an assumption groups necessarily get along, right? There’s like war going on between different countries and they had to bridge all of this. So I think that there’s so much the ways that they were able to be quick and nimble to address the kinds of ways that neo-liberalism was impacting labor and the part-time ization of labor. And it’s kind of austerity. I think there are a lot of lessons to be had for us in the current and future of organizing. That it isn’t just the old models, but it’s this quick and nimble way of working and that it will be the people most impacted who are in the leadership of these organizations. So the workers themselves leading a working class issues. The final thing I want to say Harvey, to your point, is that the model minority image covers up the working class Asian-American, in our community, and yet there’s so much in so many Asian-American suffering in all kinds of ways and we need to address that in our organizing. And we are.

[00:36:45] Janie Chen: Thank you so much, Diane. I had one question for all of the panelists. It’s how can this book be taught and discussed or introduced into our communities? And how do you envision the audience engaging with this book? What are the key lessons that you’re hoping the audience will take from it? And what does this book offer that’s different? Why don’t we start with, Ga Young.

[00:37:11] Ga Young Chung: Thanks Jenny, for your question, I believe the most unique contribution of our book is that we are covering the most up to date activism, the very radical activism that has been initiated and, presented by AAPI communities in the United States. As you can find from our contributers chapters, it is not only dealing with the issues of race, for instance, citizenship, but also it is dealing with lots of various topics such as gentrification, climate change and social justice issues, which are not only happening in the United States, but also shared around the globe. I believe that our book is really highlighting the intergenerational as well as transnational and multiracial and intersectional approaches and activism can inspire a lot of current activists as well as scholars. Most importantly, our students and next generations when they want to rediscuss like what activism and activists learning they want to have and develop throughout their community organizing.

[00:38:24] Rhonda Ramiro: I can jump in next. I couldn’t agree with Ga Young more and I was just reflecting on Diane’s description of the workers in New York, the taxiworkers who really connected their struggle to neo-liberalism. And one of the things that I think this book does is that it shows how the many struggles presented, no matter what community, are connected by common things like the attacks of neo-liberalism, the way US imperialism runs through it all and, shows that there are many different ways in which communities are resisting. And so one of the things that I hope this book can be used for is to draw that kind of solidarity among peoples, where society is trying to divide us. Read this book, understand the struggles, understand how the struggles are connected in so many different ways. And then, be inspired by the ways people are organizing, in resistance.

[00:39:24] Diane Fujino: I want to amplify something that Eddy was talking about. He was put in solitary along with his two comrades, in prison in San Quentin because they were organizing to get Asian-American studies in the prisons. There’s the whole ethnic studies movement happening in the high schools right now and I feel like this book is about Asian-American studies and ethnic studies and showing that social history. The one that you’re talking about, Harvey, where ordinary people are creating change. We’re creating the world. We want to see and we want to live in, and that’s what this book is about. And it’s fundamentally about race based movements, intersectional justice. And it’s the kind of ethnic studies that Eddy was fighting for. That Robyn was talking about our students reading and transforming their lives. So I was thinking, I hope that this book. And Eddy we’re going to have to figure this out, I know you’re working on something to get the book inside the prisons. To get it to community organizations, to university classrooms, and I’m thinking both events, but also study groups and really using this to think about how we create those movements for liberation right across the long run. Because we are, as I said earlier, we’re really trying to center organizing knowledge. I have so much respect for these long-term organizers, who struggled day in and day out. It’s not just the things that get media attention. It’s really hard work. It’s struggle. And we are trying to highlight that and to think very seriously about how we create a new world.

[00:40:53] Eddy Zheng: Yeah, the other thing I want to add why this is, this book is important, is it connects to the theory and the praxis. So sometimes, we learn and we study, and then the act of planting the seed of knowledge, right? It is that the theory, it is already engaging in that praxis. But, for people who are we highlighting, you know, in these chapters, and of course it’s not a comprehensive, like a encyclopedia but it really just like glimpse towards how, with people with lived experiences. It’s sharing how the practice of activism and bringing people together and building community and leading with that mindset of how are we going to be able to fight for freedom and then also fight for the freedom of others. And that, I think that’s important and it’s not so much an external only, but more so of this book will allow you the opportunity to focus on internally. How is it connecting to you and your mental struggles, where as you see all the injustice that you read about others, you know how these types of things will activate you to become a better person. And I think this book will have the opportunity to do that.

[00:42:09] Robyn Rodriguez: Thank you for that Eddy I just to add it to close out this part, I want to emphasize or just lift up again, what Diane has already said well as Eddy well what everybody’s already really said.

I mean, one is that, I think one of the things we’ve always envisioned is that this is not just a book to be read and sit on a shelf. This is meant to invite readers to engage. So there are a couple of ways that we’re hoping to invite people to engage in activist struggle, especially around the Asian American community. We actually created a website for the book. And a part of the hope as we go along is to be able to not only share more updated information about the movements that are discussed in the book, but also to be able to share resources that will allow different sorts of people to study the book. I mean, being able to do events like this with Eastwind and other venues is great for being able to share some of the insights from the book but we, definitely hope that it goes beyond the college classroom. We really do hope that this is a book that nonprofit organizations, grassroots groups community-based organizing. And engaged. The hope is that we’re able to share some templates or a guiding questions or curriculum that maybe, organizations can also adopt in their own kind of political education work. Just to lift up what makes us different really as Eddy has already articulated is that we, as editors, Diane and I are primarily working as scholars and working in the university, we both wanted to center the knowledge of those on the ground that we value the knowledge that organizers bring to the table, that they have a real sharp analysis of what confronts us in the world today, they have a sharp analysis and structures of power and domination. And more than that, they offer us, visions of change, real lessons around praxis. That really, I think, makes this book stand apart. I think from other kinds of books, academic books, that might be engaging or trying to highlight Asian-American activists. For me, one of the contributions, in addition to the introduction and the chapter I wrote on my own student organizing was a reflection. And the epilogue on the organizing of my son, Amado Khaya Canham Rodriguez, actually it was in the midst of really finalizing the revisions for this book that we actually got the tragic news that Amado had passed Amado was in the Philippines. He had been in the Philippines for two years, working alongside indigenous peoples. He was very much inspired by a kind of exposure program, and in his work he was biracial black and Filipino he was doing work at the intersection of his identities as somebody who had identified as black and also as Asian-American, did a lot of work, very much on the campus. many people say he’s responsible for having successfully fought further gentrification of the city of Oakland in his organizing as a college student in Laney against the A’s Coliseum construction. And then he ended up having this opportunity to learn directly from indigenous communities, wanting to commit a part of his life as a young person, to learn even further from them and to work alongside them. And so I guess one of the things I hope, and I think a lot of the contributors of the book felt was important about the Amado story and why I was invited to share that epilogue was because in a lot of ways, he exemplified some of the most beautiful lessons of our movements. He was the son of activists. He learned directly from movement elders in the black radical tradition and the Filipinx tradition. the way he moved as an organizer really offers even though, he ended up losing his life and mainly because, he died a food poisoning it’s a death that’s far too common for many indigenous peoples , nevermind the fact that they also deal with state violence. But he really lived his life in a way that I think many, of the contributors, and I think so many people who’ve heard about his story is so inspiring that we hope that gen Z- ers in particular, as somebody who was of the gen Z generation might be able to learn from and be inspired by. So with that, we have some time still for questions. So I’ll just leave it to you Janie, to pick the question to pose to us. Thank you all.

[00:46:36] Janie Chen: Thank you so much. The first question is from Sam Kim, and they asked how does Asian American activism and this book address disparate representations of the API community in their activist work especially as it pertains to class. And I think to add onto that question, how do you bring in and engage folks into this activism work folks who are coming from different levels of understanding and commitment.

[00:47:05] Rhonda Ramiro: So for BAYAN USA, we’re a multi-sectoral Alliance. And so we have organizations of workers, of women, of youth of, artists, human rights advocates and others. And so we very intentionally try to cross those boundaries that the person who asked the question was talking about even within our own community. So centering on all people, in the Philippine, diaspora can be part of this movement to change the conditions that keep our country poor, can be part of the movement. I think in the question that was asked, there was a particularity around voices of poor people and working class people. And those are the very people that bear the brunt of the repression that we see, bear the brunt of neo-liberalism today or the brunt of war in the world. so we ensure that we’re organizing working people, as a central focus of what we do so that their voices, the people on the very front lines of the crisis today are the people who are.

The leaders of the organizations are the people telling the story are the people organizing others are the people who we interview in our chapter, in the book. and from what I hear about the other chapters they’re the same people the people leading the struggles are among the most oppressed. And so I think that’s one of the unique contributions of the book is that it does seek to tear down those kinds of boundaries that could be drawn between people.

[00:48:32] Diane Fujino: I’ll weigh in just briefly on other chapters in this book. Eddy has spoken to prisons, Karen Umemoto whose chapter speaks to mostly native Hawaiians who are going through the juvenile justice system in Hawaii. I talked about the New York Taxiworkers Alliance, but I want to lift up a couple of other chapters that also speak to the working class, Asian America.

One is by May Fu and she, one of the groups that she looked at was Adhikaar, which is a Nepalese women led organization in New York City in Queens. And they’re organizing mostly women, domestic and nail salon workers. They’re dealing with temporary protected status. As refugees or undocumented. And she was looking at the kind of political education organizing that they do as well as the organizing for justice that they do. So we were trying to have a range of groups that we’re looking at. And then I also want to note that Alex Tom and Pam Tau Lee both worked or work with the Chinese Progressive Association in San Francisco.

And a lot of the work that they’re doing, tenant rights in Chinatown in San Francisco, Chinatown, they’re working with, working class Chinese immigrants and an Asian American immigrants. And so there is a focus on, different class formations. We’re also looking at students, there’s quite a bit on young youth organizing and student organizing. Some of whom are middle-class, but in any case, I think that there’s a focus in this book. And as Rhonda was talking about that centers economic justice, in addition to racial justice.

[00:50:08] Ga Young Chung: I want to add one thing about the undocumented Korean activism. There was some time when the leaders and initiatives of this activism were more led and facilitated by the previous generation, the senior generation of immigrants rights movements, but as DACA came out, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, and many young generation were able to get some, even temporarily some protection from being deported by the state. It helped many undocumented, Korean and Asian activists to meet with other colleagues and their peer groups so that they were able to expand their conversations and hope around, making their activism more radical. DACA has never been a perfect policy. It is still emphasizing the new river values, such as efficiency, productivity, and quote, unquote more characters of young undocumented immigrants, but still it positively affected enlarging the pool of this activism so that they were able to pave a more progressive way. So for now, at NAKASEC, for instance, we are really believed in the values that our activism should be led and facilitated, designed by the most impacted people as a result. Now, one of our co-executive director in NAKASEC is the undocumented Korean immigrant young adults. And as our board chair, is there some documented Korean immigrant, \ it is not the end of the story, but there has been this efforts so that we do not let this activism to be led by more, for instance, experienced and quote unquote elite activists. But try to redistribute the leadership and initiatives to be more went by the most impacted people. Thank you for your question.

[00:52:10] Janie Chen: Yeah, thank you Sun for your question it reminds me of that one phrase where it says those closest to the problem are also those closest to the solution. So we have another question from Grace Chou, a student from professor Virginia’s class. They write, I know social justice work is not a job that you can just go home and walk away from. And I ensure the work can weigh on everyone’s mind very heavily. The question is how do you separate your work life to everyday life in terms of mental wellness and et cetera? So maybe, Robyn you can take a stab at that question.

[00:52:44] Robyn Rodriguez: Yeah. Thank you for that Janie. Thank you so much for the question grace. I mean one thing is at least for my organizing , is it delimited to the fact of my job as a professor? I often say that the university just happens to pay me, but my work is to continue to work, to advance the work of advancing justice. And what that means I think it’s so much a part of totality of our lives, not just the time we put in at our paid jobs where we may not even be necessarily exercising our political work primarily. For instance, again, I get paid by a university of my political work and our political home may not be the university. It may be the university and other spaces, so there’s that. But actually I think one of the things in terms of real amazing and important lessons that I think the gen Z ers have given us is this attention to mental health. That was certainly something that I learned from my son, Amado, as somebody who was the child of two activists, I think he could see, and he would often call us out his parents around the ways that the intensity of our work as organizers, how it was impacting us, how it was creating certain kinds of traumas for us as individuals that could sometimes also manifest in the space as a family. And so I think that what I appreciate from this newer generation is this attention to mental health and wellbeing. A lot of what we unfortunately learned from our elders, there are lessons to be learned, it’s also the lessons not to repeat, which was this idea that you sacrifice yourself so completely and that your commitment was measured basically by how little sleep you got, how you were willing to work, no matter how sick and ill you were. I mean, it was a kind of all or nothing, scene. A model by many of my elders. And I felt like I had to do the same, but I also have seen those same elders struggle really hard with their health and old age, how it’s also made them bitter and resentful. It is true. The work we do as social justice, organizers is heavy work and it does require that we commit individually as well as collectively to the work of wellness and healing. We have to do that work even as we’re doing this work of calling out, all of the ways that structures of power and domination, hurt and harm us.

We also have to do the work of amplifying all of the ways that we resist. And we have to also do the work of carving out spaces of radical love, spaces of collective care, where we can also model a way of being with one another and help each other in our healing. I think that’s work that we still have yet to develop, frankly, in our movement spaces. And definitely that sort of a transition I’m trying to really do in my own organizing. I’m working with other organizing across the organizers, across the country, around advising healing justice programs meant specifically for folks who work in non-profit spaces, grassroots groups, and, community based organizations. Even as part of the Amado Khaya Foundation, that we really, that we just recently established, we actually have a retreat home that we’ve been gifting to organizers, to activists artists just as a space of rest, because we know that there are so few opportunities for folks at the front lines of fighting and justice to just have a chance to take that breath that Eddy always reminds us to do, to take that pause. So, I think that’s a wonderful lesson that we’re learning from this newer generation about the importance of drawing, these healthy boundaries, doing this work of collective care, rooting our work in radical love. So, thank you for that.

[00:56:32] Janie Chen: Thank you so much. And I think that’s a nice way to conclude our Q and A and panel event for today. So with that, I’ll hand it over to Harvey to close.

[00:56:45] Harvey Dong: Yeah. I just wanted to thank everybody for writing the book, for all your reflections on this today’s panel it really interconnects and it provides important lessons in building solidarity and the other thing is, we’re in this for the long haul. And I think the book, provides us with the strategic tips, about how to survive, cause definitely the world’s going through tremendous changes and by your writing and reflecting and us discussing all this stuff, it really does help prepare us for the future. So contemporary, Asian American activism will be like a book, one of the future. And if you want to purchase the book, it’s available at Eastwind Books of Berkeley, www.asiabookcenter.com.

[00:57:41] Miko Lee: thank you so much for joining us. Please check out our website, kpfa.org backslash program, backslash apex express to find out more about the show tonight and to find out how you can take direct action. We thank all of you listeners out there. Keep resisting, keep organizing, keep creating and sharing your visions with the world. Your voices are important. Apex express is produced by Miko Lee Jalena Keane-Lee and Paige Chung and special editing by Swati Rayasam. Thank you so much to the KPFA staff for their support have a great night.