In the ’90s, Hip-Hop music really began to take over the music industry, even though it was still dismissed by some older generations as “noise” and “not real music.” However, not everyone in the pre-Gen X generations had a distaste for Hip-Hop. One artist in particular, an icon whose stamp of approval on the genre carried undeniable weight, was Quincy Jones. Mr. Jones had his finger on the pulse of this emerging genre, with several Hip-Hop artists featured on his 1989 release, Back on the Block.

It wasn’t until the early and mid-’90s that Mr. Jones would try his hand at signing and developing Hip-Hop artists under his imprint, Qwest Records. He had barely dipped his feet into that pool with Electro-Funk, showcasing artists like Deco & Griffin, who had moments of Hip-Hop in their songs but not the full Monty. He came close with a Rockit-esque song, “No Humans Allowed,” which featured a DJ scratching. But in the ’80s, Qwest was mainly focused on artists like James Ingram, Patti Austin, and briefly, Frank Sinatra

Griffin “No Humans Allowed”

In 1991, we got Qwest’s first official Hip-Hop release with the short-lived Rappinstine and their single “The Good Life,” which was more Hip-House in style and look. Then there’s Justin Warfield, who wasn’t really taken seriously by hardcore Hip-Hop heads and was seen as kind of corny, with a very non-threatening style of rapping—safe enough to play around your parents or goofy cousins who had just discovered rap. Looking back, I think it might have been due to his appearance, as he didn’t fit the image of most Hip-Hop artists in the early ’90s. Also, using your real name instead of a memorable stage name was unheard of back then.

Maybe he was just ahead of his time, dropping a few decades too early. One of today’s biggest stars, Kendrick Lamar, made that work in his favor. Warfield’s music wasn’t really bad either—it just didn’t stand out. Granted, he did feature production from Quincy Jones’ son, QDIII, who would go on to produce certified Hip-Hop classics for Ice Cube, Too Short, and Naughty by Nature.

Justin Warfield “Season of The Vic”

As the ’90s rolled on, Hip-Hop music continued to change and evolve. Gone were the uptempo, Hip-House, and New Jack Swing era vibes, traded in for slower, funkier, jazzier, more street-level artists who would become the dominant voice in rap for many years to come. By ’92, we saw the rise of the short-lived popularity of Hip-Hop Jazz, which by ’97 would be fully replaced by G-Funk, Wu-Tang/Nas/B.I.G street rap, and eventually the shiny suit “Jiggy” era.

In the mid-’90s, aside from New York and Los Angeles, many hot regional spots were making serious noise, including Houston, the Bay Area, with Atlanta and Memphis soon to follow. Taking notice, Qwest turned to the Bay to sign two very different artists to their roster, both of whom would release debut albums in 1994—now regarded as classics and slept-on in an era flooded with big releases. This was a time when, despite claims that Hip-Hop was becoming too commercial and full of gimmicks, we were all eating well.

Warren G “This DJ”

Nas “It Ain’t Hard to Tell”

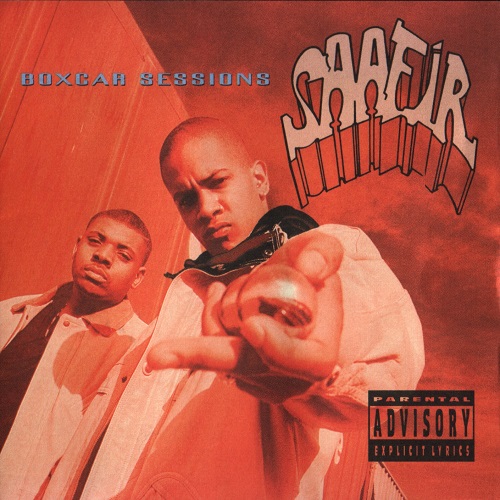

West Oakland’s Saafir released his classic debut, Boxcar Sessions, an album that wasn’t promoted well by its label but gained buzz through Saafir’s own hustle, regularly appearing on The Wake Up Show, including the legendary battle against Casual of Hieroglyphics. To me, it feels like Qwest didn’t really know how to market Boxcar Sessions. Saafir had a unique voice and flow that should have been a major selling point in promoting him as an artist. He also had a memorable role in the classic film Menace II Society, and why he wasn’t on the soundtrack is a mystery to me.

When Boxcar Sessions was released to the world, it didn’t sound like anything else in Hip-Hop at the time, both sonically and lyrically. This was an era when being unique and embracing individuality was praised, as the biggest sin was biting other people’s styles and sound. Saafir, with his signature offbeat style, threw many Hip-Hop heads off guard, as he was operating on a level many either didn’t understand or weren’t used to hearing.

I remember some Hip-Hop fans treating Saafir much like they did E-40, who was also misunderstood by casual rap listeners for not conforming to the popular, easy-to-digest rap styles, and instead doing something different. But for those who got it, loved it, and understood what he was doing, we played that album front to back until the cassette broke.

I feel like if Saafir had been marketed like a Miles Davis-type Free Jazz artist for the Hip-Hop generation, Boxcar Sessions might have been better appreciated and sold more upon its initial release. Saafir even knew in ’94 that some wouldn’t get it right away, but would, years later, come to truly appreciate its genius.

Saafir “Light Sleeper”

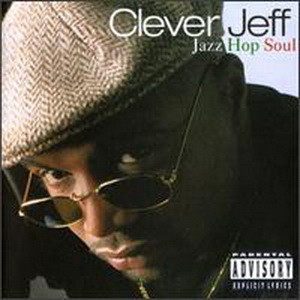

The same year, about five months later, we have Berkeley’s own Clever Jeff, who dropped the criminally slept-on Jazz Hop Soul. By 1994, Hip-Hop in the Bay had multiple rap styles. We had, of course, a variety of mobb music artists, mostly on independent labels. Too Short’s Dangerous Crew had its own sound, releasing many albums on Jive Records. And, of course, there were the many deep underground artists, many unsigned, who offered an alternative to the widely popular “Gangsta Rap” that had taken over. Camps like Hieroglyphics showed you could be successful with that style on a major label.

Clever Jeff was part of the non-Gangsta style rappers, but he also wasn’t like the battle-rap, SP-1200 gritty jazz sample cuts you’d hear from Hiero. Jeff’s sound was cleaner, polished, and very jazz-focused, catching the ears of the likes of Guru, who remixed his song, “Catch Rek.” It’s no coincidence that the two Bay Area artists signed to Qwest were both jazz-flavored. Saafir was the more abstract but street-focused emcee, while Jeff was the straightforward, cool, smooth player type.

I think if Jazz Hop Soul had been released a year or two earlier, when songs like “Cool Like Dat” by Digable Planets, Us3’s “Cantaloop,” and Guru’s Jazzmatazz were out, it would have garnered more attention. The fact that they didn’t make the two work together on a song feels like a missed opportunity—or even feature one of their many incredible labelmates. By the time Jeff’s debut dropped in late Q3 1994, hardcore street rap had begun to dominate the airwaves and video music channels. Jazz Hop Soul was just as dope as Digable’s Blowout Comb album, which also got severely overlooked and released just a week after Jeff’s debut. But that was how fast Hip-Hop was changing.

Clever Jeff “Catch Rek”