A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists.

A weekly magazine-style radio show featuring the voices and stories of Asians and Pacific Islanders from all corners of our community. The show is produced by a collective of media makers, deejays, and activists.

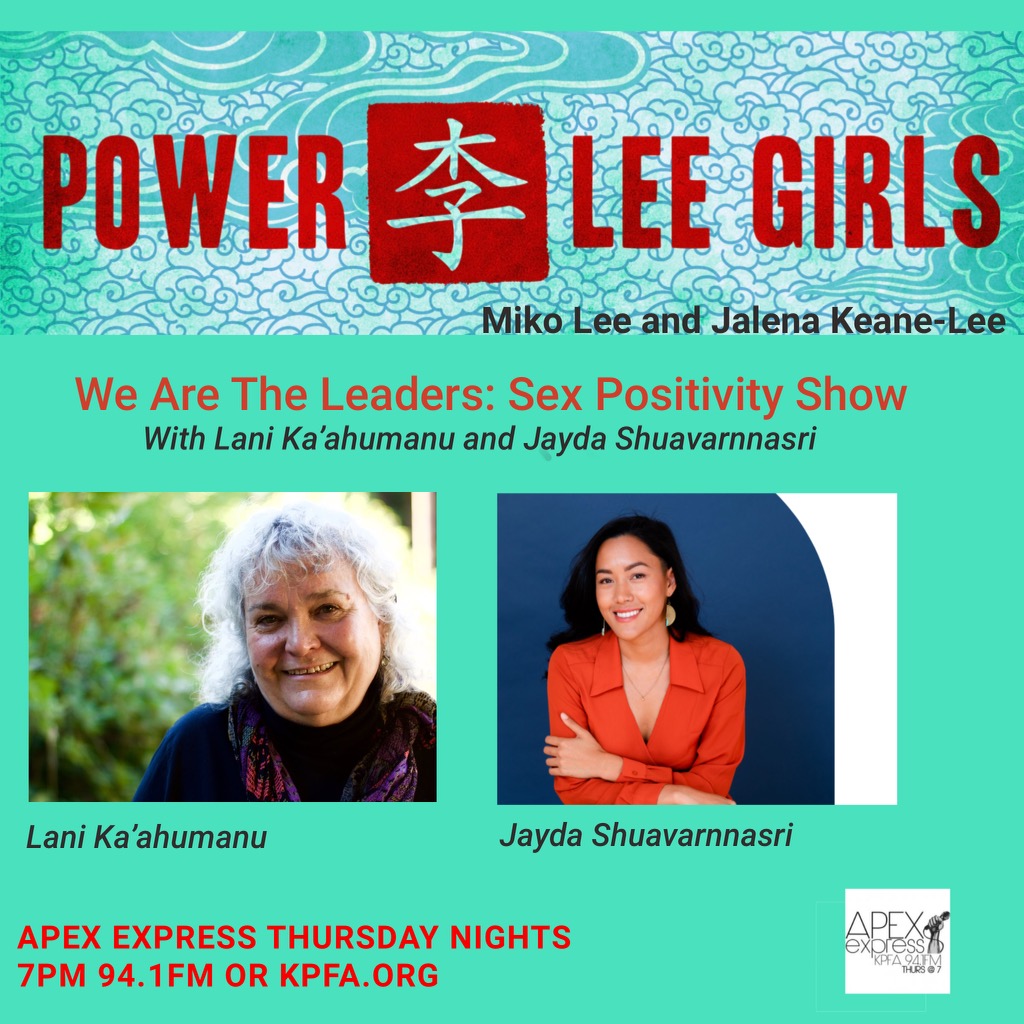

Tonight the Powerleegirls Miko Lee & Jalena Keane-Lee, a mother daughter team are continuing the We are the Leaders series – highlighting an elder activist who has broken the mold and a younger activist who is reimagining the way forward. Tonight’s focus is sex positivity. We get to hear from two queer icons who are sex educators. We talk with Lani Kaʻahumanu, a hapa queer elder who is known for putting the B in LGBTQ and founding the Peer Safer Sex Slut Team and with Jayda Shuavarnnasri a Thai-American cis queer woman also know as your sex positive Asian Auntie.

Lani’s speech at 1993 Washington DC Pride March

Sex Positivity APEX Show Transcripts

[00:00:00] Opening: Asian Pacific expression. Unity and cultural coverage, music and calendar revisions influences Asian Pacific Islander. It’s time to get on board. The Apex Express. Good evening. You’re tuned in to Apex Express.

[00:00:18] Jalena Keane-Lee: We’re bringing you an Asian American Pacific Islander view from the Bay and around the world. We are your hosts, Miko Lee and Jalena Keane-lee the powerlee girls, a mother daughter team,

[00:00:36] Miko Lee: Tonight we are continuing our, we are the leader series highlighting and elder activists who has broken the mold and a younger activist. Who is re-imagining the way forward tonight. The Powerleegirlsare talking about Sex Positivity..

[00:00:49] Jalena Keane-Lee: We get to speak with two queer icons who are sex educators. We talk with Lani, KA Manu, a Hapa queer elder, who is known for putting the B and LGBTQ and founding the peer safer sex slut team. And with Jayda Shuavarnnasri a Thai American CIS queer woman, who who’s also known as the sex positive Asian auntie.

We’re here with Jada Shuavarnnasri the sex positive Auntie. I’m so excited to talk with you. I’m curious. What got you started on your journey to become the sex positive Asian Auntie that you are to.

[00:01:22] Jayda Shuavarnnasri: It’s been a long journey, but yeah. Thank you. I have always been intrigued by our relationship to bodies and our relationship to sex as a survivor. I have always had questions about how my body was treated in the world and how I am supposed to navigate the world as a femme presenting person. And then just being around other Asian women witnessing their relationships, their romantic relationships, hearing about. Kind of the experiences that they were having. I just have more questions about sex and what it was supposed to be I found that a lot of folks in the Asian community, aren’t comfortable talking about our sexuality and we weren’t really given the tools. I definitely never had a sex talk, with my parents to this day, that’s not a conversation we’ve ever had. Yeah, so these different elements, just lots of questioning eventually led me to starting a podcast called “Don’t Say Sorry,” where myself and my friend talk about relationships, healing, and sexuality, and a bunch of other things that our parents didn’t really teach us. And that kind of spiraled to just like, all right, I’m just going to hold space for other Asian folks who are interested in talking about. That’s how I grew into a sense of agency..

[00:02:55] Jalena Keane-Lee: I love that. When I was in college, I went to Wellesley and I had a. Sex radio show that was called “Great Expectations”. And it would just be me and my friends talking about sex. It was really fun. I’m curious. So I know you said, and a part of your messaging is, you’re being the sex positive Asian ante that you wish you had. Are there any auntie figures, related or not related, of course, that stood out to you in your own development that taught you about sex and sexuality.

[00:03:23] Jayda Shuavarnnasri: Really good question. Because I actually think that I came into my, being the sex positive auntie, because I didn’t see other figures that looked like me. And so when I did see other people talking openly about sexuality, about sex, about their bodies. They were mostly white women, whether that was on YouTube or on random talk shows, Dr. Ruth that’s one of the most prominent figures and just like really older. And I actually loved that. She was supposed to a note for that and just talking openly about sex and answer questions as are both of the people that I saw. And that was part of the issue for me of just I don’t completely relate to their experiences, especially when they talk about having open conversations about sex I remember having this memory from middle school where it was in sixth grade and this girl in my class was like, talked about how her parents dropped her and her boyfriend off to the mall. And I was like, what? You’re allowed to have one your boyfriend and two, your parents know and be dropped off at the ball.

Like it was like these small little, like memories that came up for you. It was like, oh, I actually don’t know how to have conversations about sex and relationships. Or I guess the way that I was learning about sex and relationships just was from this kind of like more, I don’t know the word open, but just like something, some white lens. And so I don’t feel like I have that many folks that I like on T figures that I look up to specifically around sexuality and relationships. But now I look up to a lot of. Guidance from a lot of the queer trans people of color or radically honest about themselves and their relationship to their bodies and their sexuality, gender, and things like that. And so those I guess, are guided by now.

[00:05:29] Jalena Keane-Lee: And when you were younger, what were the places that you went to find information about sex and sexuality?

[00:05:34] Jayda Shuavarnnasri: Tumbler back in college, definitely friends. So this is the thing is I wanted to have these conversations with friends. I think my first ever sexuality class was a philosophy of sex and love my first year of college, I think, and my mind was completely opened and I was like, yo, we should talk about these things. One it’s really fun. Super interesting. But I, anytime I would try and talk about sex, like with my friends and ask questions or ask for information, they weren’t really comfortable doing that. And so I did try and talk to my friends. I think post-college things shifted a little bit, and I found friends who were just as open and really sex positive. So that really helped. But yeah, a lot of it was. Definitely YouTubers. but as a millennial, I feel like most of it’s just the internet and how I found how I learned about sex.

[00:06:26] Jalena Keane-Lee: What would it have been like for your younger self to have a sex positive Asian Auntie in your life? And what was it like navigating relationship without that kind of guidance or knowledge?

[00:06:37] Jayda Shuavarnnasri: Yeah, I think because I didn’t have. Access. I felt like I didn’t have access to non-judgemental open spaces to either like question my sexuality or ask relationship questions. Like my parents one, we have a language barrier. And two that’s just not, it’s like boys were not allowed, like not even something that should be on your radar. You’re not allowed to do this, things like that. And so I think that. Yeah, I just didn’t. And that I could talk to, and then with friends, like when it comes to peers, we’re all learning at the same time. And so a lot of us don’t know what we’re doing. And I think how that affects my or affected my, a lot of my relationships and the first kind of formations of my relationships was just that I didn’t know what was considered normal. And I didn’t know it was considered healthy, I didn’t learn how to practice proper consent. Yeah. And just like random questions about I body. Was this normal to feel this, or was it normal to do this? Not having that kind of guide guidance or mentorship yeah. Showed up in those ways in my relationships.

[00:07:50] Jalena Keane-Lee: how do you create the space for those kinds of conversations with people in your community and younger people that you’re hoping to be an Auntie for?

[00:07:59] Jayda Shuavarnnasri: Yeah. I asked a lot of questions and I think that’s always the perspective I come from. you know, when I say I’m a sex positive Asian. It’s not that I have all the answers and all the wisdom. I think like when I think of a sex positive agent on, they have like wild stories and some nuggets of wisdom to share with their nibbling. But mostly it’s like asking questions and creating a space where there’s no. For curiosity. And to me, like the spaces that I create, either in my workshops or just conversations or in one-on-one sessions, just let it be known. This is a space where your curiosity gets to T to be front and center, and that everything can be explored safely without any fear of someone shaming. Or having to feel guilty for a certain desire or a question that someone might have

[00:08:54] Jalena Keane-Lee: and in your journey towards sex positivity, what are some of the key things that you feel like you’ve had to unlearn?

[00:09:01] Jayda Shuavarnnasri: Oh gosh. I think a big one is that my sexuality is determined by who I’m dating. And that shows up in a couple ways. I think one of the biggest ones is that when it comes to like sexual orientation, so much of it is oh well, if she’s dating a CIS man. And that automatically makes me quote, unquote hetero or that, oh, I’m not truly pansexual unless I have x amount of number of queer experiences or queer relationships. So this idea that sexuality is something that exists outside of us, rather than something that is actually completely ours is definitely something that I’ve had to unlearn. And also just unlearning like a lot of narratives around shame of that, that feeling sexual or being a sexual person. Makes you less pure or immoral or like the number, like the purity culture slut-shaming narratives that we grow up with that, that those are really big ones that I’ve also had to unlearn.

I don’t think they were super deep in me, but In order for me to feel liberated in my own body. I definitely had to do some unpacking of, yeah, just like feeling shameful when I had sex with someone feeling shame when I masturbated, oh my God. I was such a big one. I shared once on a podcast episode that like I used to feel really good when I was young, this high school, I used to feel really guilty anytime I masturbated. I thought that There was like masturbation karma that if I masturbated and something bad was going to happen maybe that’s like the Buddhist version of purity culture, but I literally felt oh, if I failed a test or something, it’s oh, it’s because I masturbated the, the night before. And that’s why I failed a test. So I really had this like weird karma situation with pleasuring myself. So I definitely had to unlearn that.

[00:10:45] Jalena Keane-Lee: Oh, no,

[00:10:49] Jayda Shuavarnnasri: it was so weird. I don’t even know when I comes from.

[00:10:51] Jalena Keane-Lee: Yeah. Speaking of that, I’m curious, I want to talk more about sexual shame, but also liberation through specifically an Asian femme lens and the kind of, extra pressures and expectations that are put on us as Asian femme. Because as we know, our bodies are desired fetishize and commodified. So how does that impact your work and the importance and specificity of being an Asian Aunty? Not just any auntie.

[00:11:19] Jayda Shuavarnnasri: Yeah, that’s a big part of it. And it’s so nuanced and complicated and, even stepping into this role as a sex educator or sex positive Asian Auntie. It took me years to even say and say out loud that I wanted to do this work, that I wanted to talk about sex on a regular basis, because I was so scared of automatically being sexualized. I remember repeatedly asking myself the question of how can I be an Asian femme on the internet and talk about sex without being sexualized and when I asked people like really no one could give me an answer. It was just like, it’s the inevitable, that’s just the way it is. That’s I don’t like, that’s part of the problem. I guess I still don’t really have an answer, but I do think that there’s a difference between automatically sexualizing a person because of, what they look like and who they, what the identities are and then someone choosing to be sexual.

When I talk about when I work with people and particularly work with a lot of Asian folks, and it is just like bringing us back to our own agency over our bodies. And part of that work is unlearning the ways in which we have not been given that agency, how Asian bodies have been exploited for labor, for sex, for whatever. That’s, that is part of not only our history, but like our current present day, how we move in the world. Like we are seeing that in that lens. And for me, it comes back to helping individuals remember that they do actually have power and they do have control over. Own body and our own safety and, learning self consent. Like how does consent actually feel in your own body? Yeah, so that people aren’t crossing those boundaries with them,

[00:13:16] Jalena Keane-Lee: Self consent is really powerful language. Something in that same vein that I think about is how sometimes as Asian femmes, because of the way we’re socialized and conditioned, we can mistake the way that we’re sexualized for our value. So I’m curious how you navigate, your own pleasure and your own sexuality outside of the male or white gaze and how you unlearn this idea that the amount of attractiveness you are to someone else is somehow equated to your value.

[00:13:46] Jayda Shuavarnnasri: Interestingly enough, for me it is so prevalent to be desired as an Asian femme in the world, that it doesn’t feel that valuable anymore. Because I know the systems at play that teach men entitlement that teach men You know that my body is something to be accumulated and enjoyed for their pleasure. And it’s like all the time, like men are socialized to always desire an Asian femme body and like the cat calling or the things that feel like compliments, or they come off at some, but they’re not actually compliments or just fetishizing. Like those things. I’m like, oh, it’s literally everywhere. It doesn’t make me, it’s I’m trying to think of an analogy right now. Just because it’s so prevalent, it doesn’t make me see it as special. That sounds really weird to say it like that, but attention is always going to be there and that’s not the kind of attention that I want. Intimacy. I want vulnerability. I want to care. I want respect. I want honesty so much more than I want attention or gaze.

[00:15:01] Jalena Keane-Lee: I’m curious about some of the healing work that you’ve done. I saw that you have sensuality healing rituals. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about that.

[00:15:12] Jayda Shuavarnnasri: So a lot of my personal practice alongside therapy is coming back into my own body and listening to it. As a survivor, I know that a lot of my connection to my body was disrupted because I did not consent to things that happened to it. And so part of my healing work is learning to have a relationship with my body, where she is my guide throughout life. And so when it comes to. How to actually do that or how to actually practice that. For me, it starts with my five senses. It’s starts with sight and smell and taste and touch and recognizing when those are lit up. As I like to say I don’t know if you’re familiar with like Marie Kondo where it’s does it spark joy? And it’s. If I’m looking at something, does that spark joy for me, if I’m tasting something, what does it spark in me? This also embeds a lot of like mindfulness practices that are rooted in Buddhism of just being. And being present in what your body is feeling. And so these cons, these consistent practices have helped me just listen to the wisdom of what my body actually needs and trust her. And also be able to acknowledge when she doesn’t feel safe and acknowledge when she needs to walk away from a situation or like something that she’s sensing doesn’t feel good anymore.

[00:16:53] Jalena Keane-Lee: And how has queerness impacted your relationship to sex, sexuality and all the other stuff that you’re working that you’re working with?

[00:17:04] Jayda Shuavarnnasri: Oh my goodness. That’s a big question. It’s such a constant journey and I think when it comes to. My queerness. It’s really it’s not even that I’m learning by myself. I’m learning with the collective of other queer people and the people that I’m in relationship with. And so for me, when it comes to queerness, it’s just that everything is fluid and radical honesty is at the center of it all. You know that my relationship to my body, my sexual desires, my relationships to people are all fluid and ever-changing, and they’re never actually going to be like one box thing I could feel really I could be. And I’ll say that I’m a super sexual person one day, and then feel like I’m not feels zero desire for sex the next day and let that be okay. And be able to name that and say yep, that’s what I am too. And so for me, my queerness really informs so much of how I just live in the world, how I embody my sexuality, how I participate in my relationships and move.

[00:18:13] Jalena Keane-Lee: I’m curious how it’s shaped the way you build relationships and thinking beyond this idea of romantic relationship as needing to be like the top priority, especially I think as femmes how does it change your idea of relationships and what kind of value you place on them?

[00:18:30] Jayda Shuavarnnasri: Hmhm, so my queerness and my exploration away from monogamy happened at around the same time. I had this moment where I realized that heterosexuality was compulsory for me. What I mean by compulsory is this is the thing that everyone does. Everyone just isn’t heterosexual relationships. That’s the easy, like it was the easiest to come by for me. And that was like the norm, like the default. And so I never really questioned that too much. And the same felt is that’s exactly the same way that I also felt about monogamy, where everyone around me, everything that I saw, everything that I was. Told me that I needed to pursue a romantic relationship and needed to be monogamous. That was like one of the goals in a successful life. My journey has been unlearning, compulsory heterosexuality and learn unlearning compulsory monogamy. Our unlearning this compulsive nature, this thing that you’re taught without actually, thinking critically about it, then you just sit in a really long time about oh wait, so then what do I actually do instead? What do I actually want in this world? What do I actually want in this lifetime? How do I want my relationships to look like? And I had to ask myself a lot of questions about what it meant to feel loved. And if I wasn’t, if I was trying to unlearn not that I was like, oh, I don’t want monogamy, but it was more that I was just trying to learn everything I was taught about love and find what was true for me.

And what I have discovered for myself is the people that make me feel the most loved were my friends. And it wasn’t actually my romantic relationships. Made me feel more alive or more authentic, or, some of them did that, but for the most part, it was my friendships. Like my platonic non-sexual non quote, unquote romantic connections, whether they were short ones or long ones that made me feel the most seen. And they made me feel the most valued. And they have stuck by me longer than anyone. Any of my relationships have, any of my romantic relationships have been my partnerships. And so I really had to like learn that I learned the hierarchy that romantic relationships are the pinnacle of love.

And I think that in itself Is very resonant in the queer community where we talk about queer platonic relationships so often because in queer communities, when the rest of society is telling you that you are. Worthy of love and that you are not valuable. And you find queer folks who are affirm you in your truth and can show you the love and care that the rest of society, or maybe family members like by biological families, family members, don’t give you. Then you feel a very, it’s just like beyond romantic, or it’s beyond the typical notions of romance. It’s just this like genuine deep love and care that I wish I want all of us to access.

[00:21:51] Jalena Keane-Lee: And who are some of the role models that you draw inspiration from for your work?

[00:21:56] Jayda Shuavarnnasri: One of my biggest role models is someone by the name of Dr. Kim tall bear. They are an indigenous researcher, scholar, probably other title, but they have several writings and interviews around non-monogamy and the idea of kinship that really. Shaped my views on what love looks like. In one of their interviews, I listened to, they talk about how, on a tax form or on your medical forms, you have to check a box of like married or single, and how, for them as an indigenous person who is deeply also connected to the earth and ancestors and things like that. It’s I’m never actually single. I am constantly in relationship and that’s something that really spoke to me. Because when I really went out, going back to my sensuality practices helped me be in relationship to my environment around.

And be very present in that. And I am also always in relationship to my ancestors or my spirit guides. I am in relationship to the sun. I am in relationship to my family members and friends and my pets and my plants. And so I’m never really alone in this world and I’m never really single. And so she, she is one of the people that really shaped my kind of like understanding of what it means to. Yeah. Be in love and be in relationship, guess.

[00:23:27] Miko Lee: That was Jalena talking with the amazing Jayda Shuavarnnasri and you are listening to apex express 94.1 KPFA and 89.3 KPFA in Berkeley and [email protected]. Next, take a listen to Rocky Rivera’s pussy kills..

SONG

[00:23:47] Miko Lee: Today we get to talk with legendary Lani Ka’ahumanu, who was a student leader in the women’s studies program at San Francisco state university. Co-founded the bay area bisexual network. And co-created the peer safer sex slip team and is noted as one of the people responsible for putting the B in LGBTQ lobby. We’re so honored to have you on apex express.

[00:26:04] Lani Ka’ahumanu: Thank you. I’m so excited to be here. I’ve listened to apex express. So it’s an honor to be here.

[00:26:10] Miko Lee: We love that. Can you just first start by telling us how you are one of the people who got the B added into LGBT.

[00:26:18] Lani Ka’ahumanu: It’s a much longer story, of course, but the short of it is that the bisexual and transgender community worked together since probably the late eighties on pushing to have the B and T included. In the late eighties college campuses where the gay and lesbian groups were starting to include bisexual and sometimes transgender. So when that generation reached the nineties and the bisexual community, movement was starting to peak, and the transgender. Community too. We kept challenging the lesbian and gay leadership, the movements at all the conferences, no matter where they went. Basically it took the whole decade of the nineties to get the B and the T included with the LG. It was a long, much longer story. Reading my book, that’ll be coming out. We’ll have the details of all that.

[00:27:19] Miko Lee: You’re famous for the speech that you made in 1993, the March on Washington, where you said Aloha, my name is, can you just repeat that line that you said and why it became so well known?

[00:27:33] Lani Ka’ahumanu: Sure, “Aloha. My name is Lani Ka’ahumanu and it ain’t over till the bisexual speaks.” , the reason I said that is that there were 18 speakers of the day. There was only one out bisexual, which was me. And guess who, the last speaker of the day it was. it was a great honor, but the producer kept bringing people up on stage, , in between the speakers that weren’t programmed, , that whole stage was being taken apart.

As I was being introduced because the park Rangers were threatening to turn off the electricity. I have that line in my speech anyway, but, , it took on much more meaning. And if you see the speech, you’d see them taking the stage apart, the media tent was already, taken down. So there wasn’t any media to talk to me afterwards. So it ain’t over till the bisexual. What was was so appropriate, way more appropriate than I realized when I was writing.

[00:28:36] Miko Lee: In a way that literal imagery of you having to assert yourself in that way and being the only by speaker there really, represents some of the challenges that you’ve had in upholding your BI status within the queer community. Can you talk a little bit about that? Because I know you came out as a lesbian and then fell in love with a man. And how complicated has it been to share the evolution of your status with the queer community?.

[00:29:05] Lani Ka’ahumanu: It’s been a long journey. My heart was home. My identity, everything was with the lesbian community, the women’s community, the gay community was very separate in the seventies and, was more gay and lesbian, in the eighties. I didn’t want to pick up my life and leave. Cause my life was there and I was an activist and a community organizer. So I trusted my heart basically. And I stayed there and the more I came out, the more people came out to me who said, oh, I could never do what you did. , I’m really bisexual, but, or a lot of lesbians. Talk to me about the men. They were in relationships with actual.

And ships, but they hit it from the community and kept their lesbian identity or gay men would talk to me. And so I knew there was a community within the lesbian gay community, a more queer identified. Back then we didn’t say queer identified. I called myself a lesbian, identified bisexual to put out there where my. My history and my heart and my home and my, the work that I did before was not going to change. I kept producing women’s stances and producing all sorts of events in the women’s community as an out bisexual and. So those were, I knew the people were there. They were confessing to me, but they couldn’t be out.

And part of, coming out as bisexual, then you were seen as a traitor. You were wishy-washy, you were confused. You. Holding onto heterosexual privilege, knowledge, oh, all that stuff. And as I came out, I had to challenge every one of those myself inside myself that were in was in bed. My own bi-phobia was intense that was confusing, but the confusing thing really was, I’m bisexual, I’m not confused. Everybody’s telling you your views. I got to that point and I realized too, that there is a community here, more queer identified community within the lesbian gay community. That’s really terrified to come out.

Because of the trashing and the shunning. And because I’m a community organizer and activist, the guy I fell in love with identified as a bisexual and an anti-sexist man. And within a week and a half of us falling in love, we were talking feminist by sexual revolution. I’m not even kidding. This was 1980. And how, if we were going to have a movement with men and women working together, it had to have a feminist basis. And we went from there and look for people by central. Who identified as feminist and wanted to organize a visible, viable community. That was the point of the movement, politics, bisexual movement politics.

Batman was organizing a visible and viable community for people to come out into. And that took a really long time. And I think it is complex, but things don’t get complicated. If you stick to the truth of who you are and your stories, and stand by that and demand, respect, demanding command respect.

I kept doing the work more and more people came out then all of a sudden there’s seven of us and we’re all within different areas of the lesbian and gay community is out bisexual doing the work representing bisexuals, even though we were the only ones. We’d go to our meeting signal. This is all smoke and mirrors.

But we knew cause everybody was coming out to us. There were so many people, even lesbian and gay leaders came out to me over the years saying lesbian is just easier. Gay is easier. It’s simpler. But in fact, Bisexual and trans people and non-binary people challenge the foundation of heterosexism that either, or that’s so locked in and that, you define yourself by what you’re not.

And then bisexual, transgender nine. Binary people, gender fluid people now to sinking everything up to the core, which I love. And because now we see, it’s blown wide open, which I am so happy and appreciative of that. But in the eighties, it was the end of the nineties when we went more and we became more national.

Challenging the national organizations and the national leadership what’s exciting is that I’ve never, or rarely felt comfortable. Speaking out. I wrote a lot of letters directly to leaders and back then there was no interest. The only copy machines we had in the late or the early eighties, where if you had a job at a corporation or some organization, they had a copy machine and you’d go in early and, get the corporate copies and hide them.

That was the only way to get copies for your flyers because communication was through flyers, on telephone poles and bulletin boards, phone trees, people calling each other. So it was really different organizing. Back then. And we finally a bipole bisexual political organization. Feminist was founded in 83

[00:34:30] Miko Lee: thank you for that context setting, because I think nowadays there’s a lot more language that we utilize to talk about, gender fluidity, gender identity, sexual identity. So you’re really painting a picture for our audience of how things were really just this you’re straight or you’re gay and there’s like nothing else. When you were talking about being seen as a traitor or being shunned and you mean shunned by both straight and gay communities, by being bi?

[00:35:00] Lani Ka’ahumanu: Because I was within the lesbian and gay community. It was lesbian and gay people. I didn’t know that many straight people at the time. That was my community that was coming out and doing early HIV aids work was within. The gay community, the lesbian community, because in the eighties, they had a sexual community and the mainstream was horrified and homophobic sex phobic, errata flowback by OPEC.

When I was around like heterosexual people, they just didn’t get it. They just saw me as queer anyway. Oh, you’re just gay. The bisexual piece was they saw us as gay and lesbian people saw us as straight because you’re so locked into that.

Monosexual either. The rigidity of it. They didn’t know what to do. If you’re not this you’re that. And and I’m neither this or that, or I’m, they’re saying that, you’re many things you have to disengage from. The either, or, and I used to say bisexual movement folks, et cetera, said both end, think about it as both.

And instead of either, or you have to step back and at least allow for that continuum. The reality of the continuum. That it isn’t just these extreme edge. It’s, there’s so much life and living in between and as a mixed heritage person, good grief. I have lived my entire life on many different intersections. I was raised with a pretty fierce Hawaiian and Japanese cultural background. My on my mom’s side, my dad My dad was Irish, but then when, I scratched the surface a bit and my grandmother, my paternal grandmother spoke Yiddish come on. And I was raised Catholic.

It was complex, but I used to say I’m Hawaiian, Japanese, Irish, and post. And people, just looked at me, and you get the pat on the head or whatever it is, poor thing. But I’ve always lived at intersections and that’s my norm. And so coming out by sexual, I had to, because I was really by phobic when I came out, I had to live through every stereotype, every single one. And I just knew that my truth was, yeah, I’m bisexual. That’s what it is.

[00:37:30] Miko Lee: Can you talk to me about how the safer sex sleds performance troop came to be

[00:37:35] Lani Ka’ahumanu: sure the sacred sex slut. Started out as S getting people’s attention. It’s what we were called, the peer safer sex slut team, and we are dedicated to demolishing denial, and it was American foundation for aids research grant that Lyon Martin got. Then I became the project coordinator and there were three different sections.

And the main one that I oversaw was research on young lesbian and bisexual women who went to bars and clubs, dance clubs, to find out what they knew about safe sex. If they practice safe sex, what, cause there was nobody had ever. Nobody had ever asked that population or studied it. And so I got a group of women together.

That was my job. And we were going to go out to the clubs and ask for questions and handouts, safe sex information, and that’s to get 900 interviews. That’s really hard. So we ended up performing a little bit to get attendance. And so in this peer safety, excellent team we started doing performances and then there was a lesbian sex club called ecstasy lounge. And I went there once they took over men’s sex clubs once a month.

And I went there once and they did a little safe sex thing that quite frankly, was really boring. And just I kept thinking, oh God, that’s a great, this is a great place to do safe sex skits. We started doing skits and because we were in a safe sex club, we actually did live safe sex to show women how to do it, which was pretty radical.

I got up and talked and it was funny because Elizabeth Taylor was one of the main funders and founders of the American foundation for aids research. And I would always thank Elizabeth Taylor for bringing us together and we had what was wonderful about the team. I opened it up to friends who I knew would join and have a great time. Other people joined and it was an amazing mix of, there was about 12 women at first and it ended up being about half lesbian, half bisexual. Th there was a that half women of color. There were three API folks. It was, we were an amazing group and became very popular to the point where people would follow us around because in the sex club, we could actually explain things through little skins and So people would come, into the sex club.

A lot of wide-eyed people from the suburbs, which was interesting. And we would do our skit and talk about it and then do the interviews because it was a captured audience. When you go into a bar with a loud music and drinking, it’s you lose your voice after a while asking questions. And when the grant was over it was so popular.

People were still asking us to come do workshops and do this and do that. So I loved the work. I loved being able to communicate age, sex, body, positive information. It was a gift that job I worked through so much sex, negative shame, all that stuff that It was freeing. And I opened it up anybody over 18 different abilities, different identities, different genders, different. It doesn’t matter because when somebody came to me for a work. I could put, pick from a pool of people that would represent those people.

Just a really short example, the American library association contacted me a bisexual woman. I know. And she says we’re going to be in San Francisco. And we heard about the safer sex sluts, and we’d really like you to do an educational program for us about how it works.

And I got ahold of Elizabeth, one of the sleds, and I said, okay, we had her planted in the audience. She looked like a librarian. She had very, whatever that means, conservative. And I did my talk. And then in the background, the song from music, man, Marian, the librarian came on and she got up from her seat.

And as she’s walking up to the stage, she was doing a strip and she got down to her negligee a and she got down to a garter belt with a dental dam. And the music stopped. And I said, and this is how we do it.

And of course, they were laughing and screaming and clapping that you just appeal to the audience. So there it is. Marian the librarian. We did skits like Goldilocks and the three barriers. So you add humor. Humor is one of the best things. To get something across because as I learned from my friends that did nuclear disaster humor, they said, if the information is so heavy, they can’t take it in, you just plant a seed in their brain.

So the next time they hear something about it, it goes to that part of the brain. And so I just felt that. The safe sex information, if you give it a visual, because so many women came up to me and said, I don’t learn unless I see. And the value of the safer sex. Is that I can see what to do and how to do something. And oh my God, you’re bringing, this is bringing up so many delightful, fun, and satisfying memories for me because of the work was so important is still so important.

[00:43:31] Miko Lee: So it really feels like this safer sex performance troop is about engaging folks, teaching them about safe sex and then doing it in a fun, interactive way. , and I know that you have a background as a poet, as an artist. And I’m wondering how your artists activism, intersex. How do you use the artists part of you to feel the activist part or is it just so intertwined that you can’t really take one apart from the.

[00:43:59] Lani Ka’ahumanu: When I first came out in the eighties what you had was gay papers and lesbian papers that came out once a week and that’s how we communicated. So it was a way to get visibility. One of Bi-polar people always had a letter to the editor, something bisexual, and the bar people would put a different, put a bi-phobia title on it, which was always exams for the bay area, reporter newspaper.

It’s still around. So it was newspaper. So I wrote an article in 1982 called by phobics. Some of my best friends are for plexus newspaper, which was a women’s newspaper and women’s back then equal to lesbian. And everybody thought the publisher, everybody thought, oh, this is really good. And two other women said things in and it was the bisexual issue and it’s oh good.

We’ll get a conversation going. And the letters to the editor. What was interesting, is that not one letter to the editor, it was like, that whole issue never happened. They were shocked. I was shocked too, because I thought, oh good. We’ll have a, a way to facilitate a conversation. So writing was a way to get visibility for the community that yes, we’re out here. Hey, join us. Hello. And then. The other way with the poetry, my poetry just comes out I started. Doing speeches and stuff and sometimes poetry would come out and it just was woven into the work I did. And I still do actually.

[00:45:38] Miko Lee: Love it. So as mentioned before, tonight’s show is focused around sex positivity, and you mentioned we’re interviewing also Jayda, who has this site called your sex positive Asian auntie. And they’ve basically created this open-minded person. They wish they had when they were younger. So I’m wondering if you had somebody, when you were younger to talk about your sexuality with,

[00:46:02] Lani Ka’ahumanu: I was born in 1943, which means I was a teenager in the fifties where nobody was talking about. You never heard anything. You never, I never heard the correct language for any body part. I grew up with a peep, what the hell is that?

[00:46:20] Miko Lee: Wait, say that again.

[00:46:22] Lani Ka’ahumanu: A peep like a little chicken.

[00:46:24] Miko Lee: Oh wow.

[00:46:25] Lani Ka’ahumanu: I grew up with a peep beep and there was no language, no word. And okay. Let’s go to the library just to get a book. All the books on sex or sexuality were all locked up. You had to go to the librarian and ask for a book. She would unlock the shelf. You would have to tell her which one will you know, you go through the cards. And get the card, the name of the book, write it down and go to the librarian, so there was no information. Sex was not like on early television or radio. There was no information at all. And I remember in the fifth or sixth grade, my friend, Connie drew some pictures, like stick people. And one had a penis and the other one had a, there was nothing there

And then in high school, we just started figuring things out little by little bit. I was also raised Catholic. So it was, there was a mix of. Misogyny shame bought lot of body shame and silence. I am, then I’m figuring it out, figuring out once I started, like making out or French kissing, how do you confess that in the confessional? So my friends are nice, decided it was impure, thoughts and deeds. And so we didn’t have to say it because it was so embarrassed to say what we were doing. So no, I had nothing. I would have loved to had anything at all. And auntie somebody, but there was really nothing. We just figured it out as we went along.

I’m sure there were other families that handled it better than, better than mine. My mother I was 16 and she handed me, she had very tiny handwriting. It was on, yellow pad paper, the extra long one, it was 16 pages long. She gave it to me front and back. She goes here, you need to read this. And it was all about all the different kinds of men and the what to watch out for. It was all her knowledge about sex and sexuality.

[00:48:31] Miko Lee: This is something that she wrote out for you on legal paper for you to read?

[00:48:36] Lani Ka’ahumanu: Yeah, but she handed it to me and at 16 or 17, . And she, and the thing that really got me angry, she goes. When you think your sisters are ready, please pass it down to. It gave me the whole responsibility and I was an angry teenager and I just thought that I didn’t, I hardly read the whole thing. It was just like too much for me too much. And I remembered what I did remember was number four, male number four that you watch out for was a Wolf. And that when he gets you in a position where you can kick him, you kick him as hard as you can and you run away.

[00:49:18] Miko Lee: Wow.

[00:49:20] Lani Ka’ahumanu: I know.

[00:49:21] Miko Lee: What did you do with this 13 page treatise?

[00:49:24] Lani Ka’ahumanu: I know it is a treasure to be sure. I had no idea. I still had it until I moved out of the city to do my book and. I found it, I had it and I just tucked it away and I know exactly where it is now. And my daughter. And she goes, wow, this is pretty good for backs.

[00:49:47] Miko Lee: Even writing you that long letter, that’s pretty incredible. Did you end up, did you end up giving it to your sisters?

[00:49:54] Lani Ka’ahumanu: No, I was just angry. She gave me that much responsibility.

[00:49:57] Miko Lee: I hope that entire letter goes into your book.

[00:50:00] Lani Ka’ahumanu: I’ve got a lot of archives and that’s one of the things that’ll be in my archives. And I’m sure because they became a. Safe sex and sex educator. I think it’s a interesting deep background for sure.

My book is called my grassroots or showing, stories, speeches and special affections. So it’s my memoir, my activist organizer memoir that we’ll have some background on my history, it’ll cover some of my work in the sixties. As a young housewife, getting involved with social justice, black Panther breakfast boy, cutting grapes, Cesar Chavez, UFW organizing and peace work. . Getting into the seventies and coming out as a lesbian and lived through a lot. I marched for the Harvey milk and was part of that whole amazing and a very high times and very low times when he got shot and killed her, he in Moscone. But and then coming out as a bicycle and then it’s the eighties and nineties, especially they coming together and the organizing of a bisexual community and movement.

And pushing all the envelopes and connecting in with the transgender people and their movement and standing together with them in the nineties

And of course there’s other generations and it’s so exciting. That’s one of the exciting and fulfilling. Things for me is how many generations and that w young activists actually from all over the world, email me and ask me questions about history.

And it’s yes, I feel so honored. I feel so honored that the gender fluid, non-binary people, it’s like the right direction. Let’s break down all of the, all those either or all down. So it’s all of us because if we’re going to, if we’re going to save this earth, us human beings we need to open ourselves to love that the basic of all my organization.

Organizing, that’s going to make a difference, has to be based in love, including loving the earth and learning how to love each other as human beings. Our identities are really important to us, to all of us. It’s a way to communicate with each other and to understand things in more complex ways and bottom line. We’ve got a lot of work to do as humans beings. If we’re going to save ourselves and the earth and, bless us all, we’ve got to do it now.

[00:52:46] Miko Lee: Lani Ka’ahumanu thank you so much for your amazing work.

[00:52:51] Lani Ka’ahumanu: Thank you. This has been a pleasure.

Thank you so much. Houma new for joining us and next up listen to girl gang by Rubia Ibarra

SONG

[00:54:59] Miko Lee: What were your takeaways from the amazing icon Lani?

[00:55:02] Jalena Keane-Lee: this was such a good show and Lani was so incredible. I really loved the interview that you did with her and learning about her whole process in getting to be an LGBTQ and also her speech during the March on Washington. I had no idea that that happened. , So I feel like I learned so much from her and the way she described, the sex education classes slash performances that she did with her group and how to use humor to spread really important messages was all just so fantastic to hear about.

[00:55:34] Miko Lee: I love how very different both of them were. And also how I think that these two people would really adore each other. I was talking with the Lani saying you two should meet and teach a class together. You’d be so great. And Lani said, hook me up. Let’s do it. Let’s do an elders and folks talking about sex because we really need this. I really learned from Jayda about Accepting yourself and your sexuality with who you are, and that the labels are not as important as much as Lonnie was working to really get that B in there. And how important that was at the time. And, and Lonnie talked to me about how queer was not even a word. Then that was a word that was considered a pejorative. And to hear Jayda talk about queer as something that’s really based around the person. I just love what they’re trying to do, just to be able to say I’m going to be for other people, what I didn’t have for myself.

[00:56:31] Jalena Keane-Lee: And I actually think both of them really did that, I feel like that was a big, common thread.

[00:56:38] Miko Lee: Yeah. And I just love that here are two bold Asian, fems that are out there talking about sex, not with any sense of shame, not with any sense of oversexualization or fetishization, but really trying to say this is a normal part of who we are, and we need to just be upfront about it and have open conversations about it. I thought that was really empowering.

[00:57:05] Miko Lee: Thank you so much for joining us. Please check out our website, kpfa.org to find out more about we are the leaders and the guests we spoke to and how you can take direct action. We thank all of you listeners out there.

Keep resisting, keep organizing. Keep creating and sharing your visions with the world. Your voices are important. Apex express is produced by Preti Mangala-Shekar, Tracy Nguyen, Miko Lee Jalena Keane-Lee and Jessica Antonio. Tonight’s show was produced by your hosts, Miko Lee, and Jalena Keane-Lee thanks to KPFA staff for their support and have a great night.