By Ariel Boone (@arielboone), KPFA elections reporter

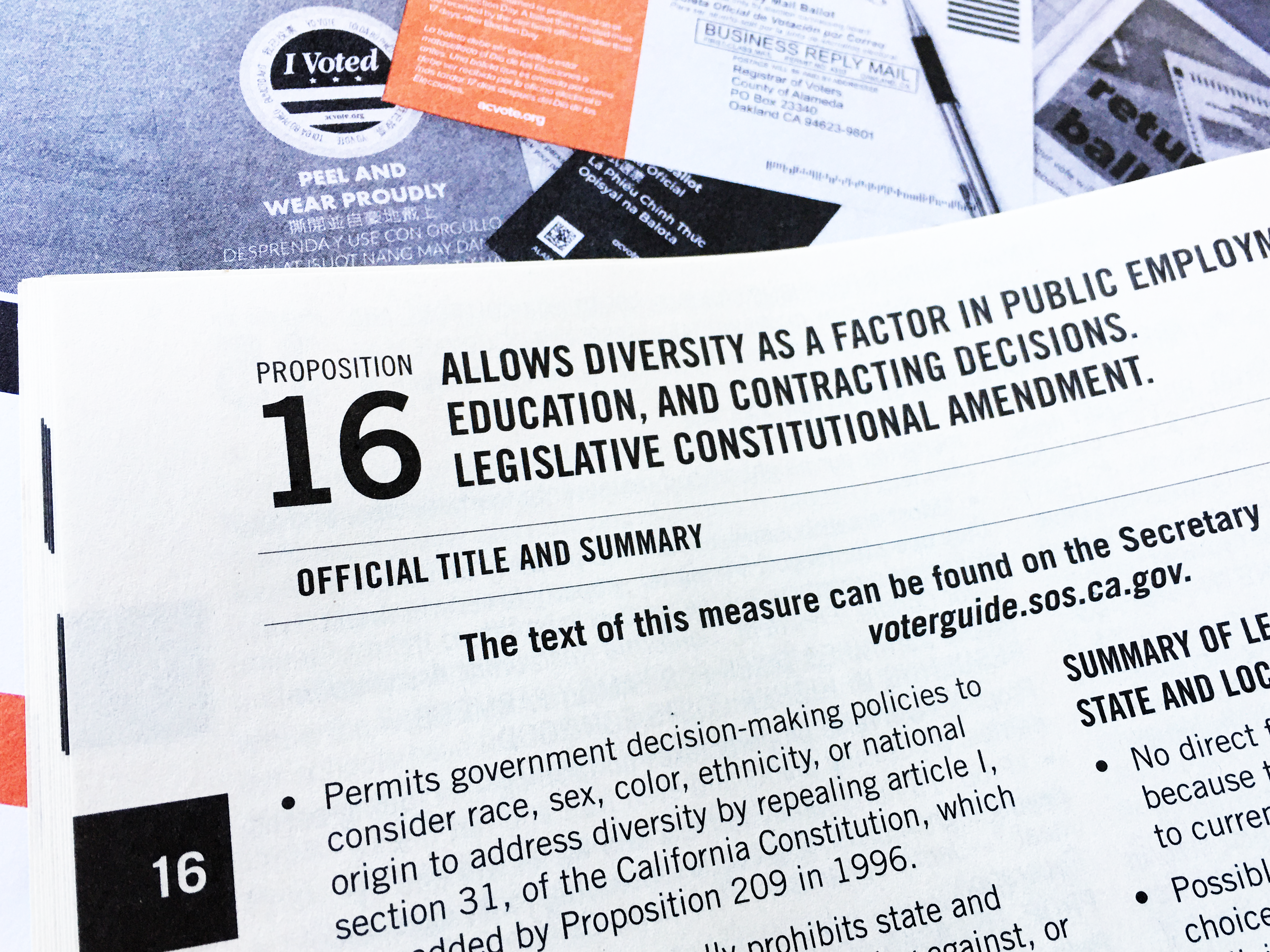

OAKLAND, CA – California is one of only ten states that ban affirmative action by public institutions. Voters put that ban into the state’s constitution in 1996. But that could change this fall, when voters get a chance to overturn the ban with Proposition 16.

Affirmative action was a response to the civil rights movement. It means an institution considers race and sex when they review applications for a job, for admissions or for contracting, in order to include categories of people they’ve excluded in the past.

Sharon Elise is a professor of sociology teaching at California State University, San Marcos and associate vice president for racial and social justice in the California Faculty Association, the union representing faculty on CSU campuses. She calls herself an “affirmative action baby.”

As a Black student, Sharon received a scholarship from a private college to attend. After, she enrolled at UC San Diego, where there was also programming to support Black students, including tutoring and social support. Then, she was hired to teach.

“I first started off at Fresno, and definitely I was an affirmative action hire, and what that meant is you’re still very outnumbered. You’re one or two people of color in a program that was beginning to diversify against the sea of whiteness that had been its historical legacy.”

Then the sea of whiteness came roaring back.

“There were years that I was the only Black woman tenure-track faculty member on my campus. Years.” – Sociologist Sharon Elise

in 1996, California conservatives ran an initiative to end affirmative action in government contracting and at public universities and colleges — Proposition 209. They framed it as a ban on “discrimination” and racial preferences. Then-Governor Pete Wilson campaigned on it, and used its success to launch a presidential bid.

“Affirmative action preferences are quotas based on race and gender,” he said, announcing his run for president. “They are inescapably unfair and they are undermining a fundamental American dream.”

Republicans were turning to affirmative action as a “wedge issue.” They wanted to split white voters from the Democratic Party, using the language of “anti-discrimination.” Wilson lost the nomination, but GOP presidential nominee Bob Dole started stumping for Prop 209 himself. Dole lost the presidency, but Prop 209 passed.

Suddenly, every public university and college in California had to terminate its programs for recruiting and supporting students of color.

“For Black people, anything for Latinos, anything for Filipinos, this stuff just disappeared overnight, practically,” Elise says. “And I will tell you in practice, it meant there were years that I was the only Black woman tenure-track faculty member on my campus. Years.”

Students stepped in to try to recreate these support programs in their spare time, unpaid. Meanwhile, UC Berkeley’s admission rate for African American students dropped from 50 percent to 15 percent.

“Without saying, ‘You know, you must look really hard at these people and do what you can to create pathways for them,’ it’s not going to happen. And it does not happen,” Elise notes. “When we say we needed affirmative action as a tool to fight discrimination, it’s a fact. Because without it, we see the results.”

California voters are now deciding whether to approve Prop 16, which would repeal Prop 209 and strike the ban on affirmative action from the state constitution. The challenge for Prop 16 supporters is that their opponents also use the language of anti-discrimination.

Gail Heriot is a law professor at the University of San Diego, and a co-chair of the No on 16 campaign. She says affirmative action discriminates against white people and Asian-Americans. “There have been many times in history where the United States of America has engaged in racial discrimination for reasons that were thought to be good and sufficient at the time. And almost always, we have come to regret that kind of decision.”

Heriot argues affirmative action is bad for Black and Latino students. She argues underrepresented students who would benefit from affirmative action are better off going to less competitive schools.

“Almost a hundred percent of the students who are getting that preferential treatment, they’re going to get grades that are low. And that’s not doing them a favor. They’re much better off going to the school where their grades will be high, they’re more likely to go on to graduate school.”

Opponents say these statistics have been debunked. A 2020 economic impact study by the UC Office of the President showed the opposite of Heriot’s claims — Prop 209 didn’t just push students of color off the most competitive campuses onto other campuses, the study said. It pushed them out of the UC system as a whole. Systemwide, Black, Latino and Native American student enrollment fell 12% in the UC system after 209. Applicants in the years after 209 took effect earned, on average, 5 percent lower wages between the ages of 23 and 35. Plus, the number of Black or Latino students who became high earners ($100,000 and above) fell. And the study showed the grades of students of color actually suffered in the sciences, engineering and math after 209.

Heriot also cited Brookings research saying Black students don’t study as much as Asian-American students: “I’m saying that they, that compared to Asian students, they don’t study as often. Is that likely to affect grades? Will you think about that?” she said.

Vincent Pan, a co-chair of the Yes on 16 campaign and a director of Chinese for Affirmative Action, called Heriot’s claim “racist lies.”

“In some cases, you do have real disadvantages for students of color in terms of what classes are even offered at their schools,” Pan says. “And so when you have a GPA system, for example, that weights advanced placement courses higher, but you don’t have equal access to advanced placement courses. You do have these built-in systemic disadvantages facing students of color, including African Americans. But when they talk about, ‘Well, this group doesn’t study as hard or are not as qualified,’ then you really start to see their true colors.”

Heriot also said California’s ban on affirmative action has saved the state money by letting it pick lower-bidding contractors.

But a 2015 study by the Equal Justice Society found that this had consequences — California businesses owned by people of color and women have lost over $1 billion annually because of Prop 209.

Pan says it “can’t be understated” how much of an economic loss this was for the state, and for struggling neighborhoods that lost this money and are experiencing poverty.

The Yes on 16 campaign has support from the founders of Black Lives Matter, the family of Martin Luther King Jr, Senator Kamala Harris, Governor Newsom, the ACLU, and California teachers and nurses. It’s also drawing support from a new generation of students.

“There’s only been one professor I really connected with, and it’s a professor who also Latino, who’s also first generation.” – Jose Lopez, UC Merced student

Jose Lopez is external vice president of student government at UC Merced. He says he knows how it feels like to be not represented on campus.

“There’s only been one professor I really connected with, and it’s a professor who also Latino, who’s also first generation,” Lopez says.

Over half of California K-12 students are Latino. But as of 2018, Latinos made up just 12 percent of tenured faculty at the UCs, CSU campuses, and community colleges.

“As a first generation Latino student from a low income household, it was always very difficult for me to access higher education,” Lopez continues. “When I was a senior in high school, I had no idea about the ACT that I had to take in order to enroll in higher education. So I kind of had to wing it, and I had no practice, I had no study. And I feel like it’s different for other communities who have those resources compared to us. And I feel like that would greatly change the representation in higher education, if students have more access to these types of resources with affirmative action.”

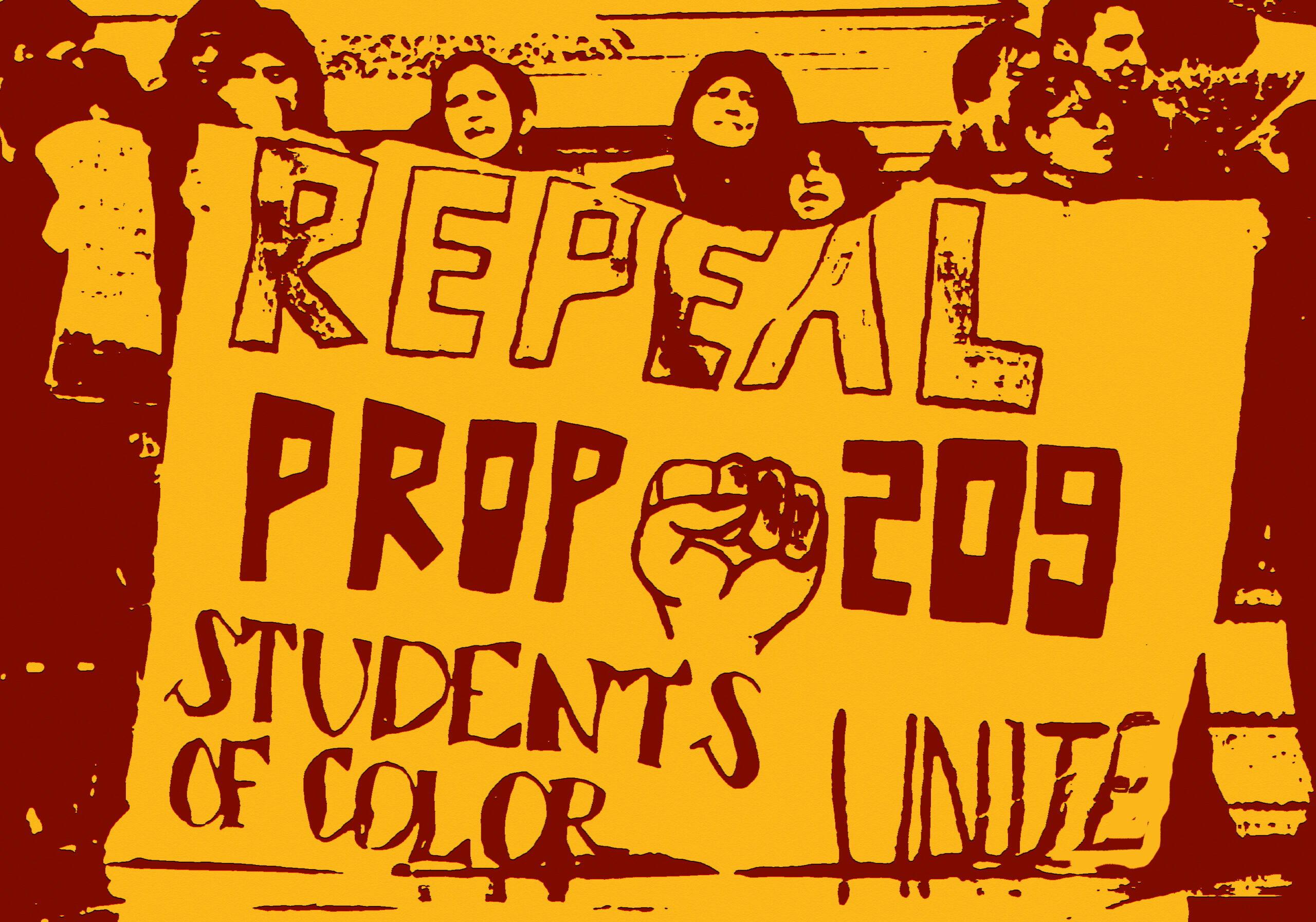

When California’s original ban on affirmative action was on the ballot, students like Jose and professors like Sharon Elise were protesting on almost every campus in the state. They lost, but the fight politicized a generation.

But right now, campus rallies aren’t possible right now because of remote learning and Covid, so students like Jose are texting and phone banking each other to organize for Prop 16.