“The song has ended but the melody lingers on”—Irving Berlin

When I heard the news of Ella Fitzgerald’s death, I took it very hard. I knew it signaled more than the end of the greatest jazz singer of all time, whose remarkable career spanned six decades and whose incomparable body of work is not humanly possible to recreate. As long as Ella was alive, I knew that the great American song had an ambassador. And perhaps, there was still hope that some enlightened broadcasters would embrace popular standards and give them renewed life on the radio. If this sounds like the sentimental ramblings of a former PD who once programmed America’s best, please indulge me.

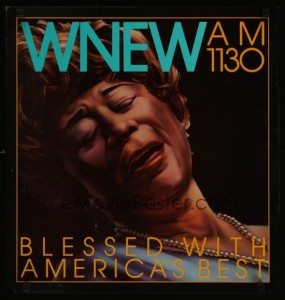

For almost six years, I programmed WNEW/AM 1130 in New York City. WNEW was the first station to play recorded music, introducing the world to Frank Sinatra and the First Lady of Song, Ella Fitzgerald. WNEW was more than just a radio station; it was a cultural institution that kept the city pulsing to the sounds of the Gershwins, Duke Ellington, and Irving Berlin.

My love affair with Ella was well-known all over New York City. Every Saturday for two years, Ella and I would spend the afternoon together. Some of my friends and associates called it a shameful love fest; I called it Everything Ella on WNEW—two hours of nothing but Ella singing with the greatest musicians in the world.

My love affair with Ella was well-known all over New York City. Every Saturday for two years, Ella and I would spend the afternoon together. Some of my friends and associates called it a shameful love fest; I called it Everything Ella on WNEW—two hours of nothing but Ella singing with the greatest musicians in the world.

“Listening to Ella, I sometimes find myself thinking, it is not so much what she does, or even the way she does it, as what she does not do. What she does not do, is anything wrong. Everything seems to be just right.” —Henry Pleasance

The magic behind the music of Ella Fitzgerald and her peers is its resilience and ability to pass from one generation to another. Millions of people don’t know how or why they can easily sing along with “Stormy Weather,” “My Funny Valentine,” “Stardust,” “Night and Day,” “Summertime,” “Autumn in New York,” or “Over the Rainbow. The answer is that these songs are part of growing up in America.

But now it looks like this tradition is coming to an end. WNEW, for example, is now part of radio history. In ‘NEW’s last years, it suffered from leveraged buyouts, junk bonds, and cutbacks at the hands of cold-blooded suits that took over the station chanting the mantra, ”This is a business, not an art form.” I remember voicing my concern for the life of the station to the great air-personality William B. Williams, the man who coined the nickname “Chairman of the Board” for his good friend, Sinatra. “As long as men and women fall in love and discover love songs and lyrics, the melody will linger on,” Williams said.

These days we only have a handful of stations playing a mix of standards, big band, jazz, and Broadway show tunes. Imagining the day when you can scan the dial and not hear the likes of Lena Horne, Louis Armstrong, Judy Garland, Count Basie , Benny Goodman, Tony Bennett, Nat “King” Cole, Mel Torme, Rosemary Clooney, Frank Sinatra, or Ella Fitzgerald is to me a deadly serious issue. In recent years, this music has been typecast as appealing only to listeners over the age of 50. Thus the music is usually relegated to the AM band, denied the energy of FM fidelity and verve. This reputation is a hard sell to bottom line-oriented managers and ad agencies, who are always in hot pursuit of young professionals.

But remember, it is those very same young professionals who made Harry Connick, Jr. a singing sensation and concert draw. Those same young professionals buy tickets to see Michael Feinstein, Liza Minnelli, and Frank Sinatra, buy his duet CDs, and dine at Cafe Carlye to catch Bobby Short or to see Weslia Whitfield. (at the Algonquin Hotel) In general, the cabaret club scene around the country is very healthy. Broadway is making money with revival musicals like The King and I, which is studded with standards. Singers ranging from Willie Nelson to Carly Simon and Linda Ronstadt have recorded successful albums of standards. This is the music that got America through her wars, depression, recessions and has more to say about family values than any politician. But most important, it is the spirit of this music—and who and what it represents—that makes it timeless.

“Ella Fitzgerald singing is like sugar in sound.” —Jon Hendrix

Ella never lost her “Sweet 16” voice. And it’s true that we’ll never lose Ella, as long as we have her recordings. Whenever she is played, her music will live on, and even spread.

Working on this column, I was listening to Ella singing from her series of Songbook albums, which celebrate such songwriters as Cole Porter, Harold Arlen, the Gershwins, Rodgers and Hart, Ellington, Jerome Kern, Berlin, and Johnny Mercer. Several young women on staff popped into my office (ages 23-26) inquired who the singer was and what the names of the albums were. They were genuinely excited about what they were hearing. Later, at home, I was listening to Ella scatting her way through “Air Mail Special” at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1957, when my three-year old son, Louie, entered my office and started dancing and imitating her furious improvisations. When the tune hit its big finish, Louie grinned at me and said, “This lady be good, Daddy.”

For years, Ella suffered from diabetes and the eyesight and circulatory complications it produced. In 1993, I heard that her legs were amputated below the knees. My mind immediately flashed to Ella on stage at Carnegie Hall, bowing gracefully after her third standing ovation. That’s the Ella I’ll always remember—the timid, shy woman whose pure and innocent singing had such sweet-natured power over her fans. It was the power of everything Ella.