Community of Grace resident Gilberto poses outside his home.

THE COMMUNITY OF GRACE

Just about everywhere in this country, and especially in California, and especially in the Bay Area, homelessness is on the rise. The most visible signs of this are the clusters of tents and RVs that seem to spring up everywhere there’s a little stretch of unclaimed land. They get covered a lot, but usually only when there’s a fire, or an eviction – some kind of crisis that throws the people who live there into conflict with city officials. But there are a lot of people living their day to day lives in those tents and RVs. There are a lot of people trying to figure out how to get their needs met, under very trying circumstances. Our long-form reporter, Lucy Kang, spent more than two months visiting, recording interviews, and learning the rhythms of daily life at one place called the Community of Grace: the rules they live by, how it enforces them, how people wound up there, and where they hope to get to in the future.

Click on these links for an excerpted audio journal from Markaya, a Community of Grace resident and an interview with Dr. Aislinn Bird about addiction support services available to people experiencing homelessness.

“This is the Community of Grace.” – Maria Fuentes, resident

There’s a story from KCBS that really irks Maria Fuentes.

In it, reporter Holly Quan recounts, “It’s like a Mad Max movie, a post-apocalyptic scene with a guy setting a fire in an empty oil drum, a dead rat rotting in the middle of a dirt road surrounded by RVs.”

“That’s embarrassing,” says Maria. “I’ve seen clips of those movies and that is nothing nice.”

The report with the Mad Max comparison was about the place Maria lives. The city of Oakland calls it a homeless encampment. But the people who live here use a different name.

“This is the Community of Grace, in case you guys don’t know,” says Maria. “That’s the name of our community, Community of Grace.”

It’s named after one of the original founders. Her name was Grace Valles. She passed away in her truck – one of the many unhoused who die on the streets but whose numbers are uncounted because neither the county nor the state nor the federal government track that data. Her husband didn’t want to be interviewed. But he still lives here, across the corner from Maria.

The community is at the intersection of Alameda Avenue and East 8th Street, between a Home Depot and the 880 freeway. It stretches along two streets and one city-owned patch of dirt, where there’s a collection of cars, RVs and tiny houses. The tiny houses are made of wood and have working doors and windows and weatherproofing. But they’re each the size of a single bedroom.

Maria says when she arrived five years ago, this was just an empty corner lot, overflowing with garbage. She and some friends thought, if they just cleaned up the place, maybe they could stay, at least for a little while. Now, Maria makes it her business to know everyone who’s moved here.

“I’ll sit there and go through every person in my head from each trailer to each trailer, each tent, each structure,” says Maria. “We’re at 48 right now… It usually stays from like 40 to 50.”

Maria is like a community mom. She solves problems, reminds residents to clean up after themselves, and checks on people. Two other residents come up to her to chat, Flaco and Isaac. Flaco says he’s been homeless for a year; Isaac for twelve. Flaco says he used to be a truck driver, but was forced to stop.

“They no like me anymore,” he says. “I’m too old.”

“They no like me anymore. I’m too old.” – Flaco, resident

A lot of the people here treat each other like family. And everyone I talk to says the same thing: they want to stay. Take Lisa, who lives in an RV along a dirt path lined with vehicles.

“It’s safer than living on the street,” she says. “And we came from the street where we were moving around all the time and people were getting their stuff towed and things taken by the police. So this is safe.”

Lisa owns one of the few working cars. She drives for Lyft sometimes and also helps out other residents.

“So I take people to their doctor’s appointments, to the store and you know different places to you know, get gas and different places. You know, that’s pretty much the normal day, waiting for somebody to say, Lisa, can you give me a ride?” She laughs.

There’s one thing everyone here has in common. Lisa starts to tear up when she talks about it.

“There’s just no way that they can, any of us can afford to live anywhere. There’s no housing available. So we have to do what we need to do to survive.”

“There’s just no way that they can, any of us can afford to live anywhere. There’s no housing available. So we have to do what we need to do to survive.” – Lisa, resident

But they don’t know how long they’ll be allowed to stay. People who run nearby businesses don’t see the community the same way that residents do.

Bay Island Gymnastics is just across the street from the Community of Grace. It’s a warehouse space where kids learn gymnastics and parkour after school. Owner Jennifer Engle leads me around her space.

“Outside is the fun area: trampolines, bars, balance beam, spring floor,” she says. “It’s like a children’s play land.”

Jennifer says she sympathizes with the people living across the street. But she also worries.

“My biggest concern is not the people that are down on their luck and trying to live the best they can in that environment. My concern is more for the mentally unstable people and the people that are on the drugs.” She gets choked up at one point talking about it. “I feel really bad for them. It’s really gotten quite sad. I’m sorry, it’s just, it’s very it’s very emotional to see it.”

Jennifer bought Bay Island in 2005, about a decade before Maria arrived. She has not liked the changes.

“We see things. And when I say we, I’m talking about my families, my staff, children who come to the facilities, prostitution, drug deals, drug labs, people who need help, kind of yelling obscenities walking down the road.”

Jennifer’s customers and staff complain. She says enrollment in her morning programs dried up. So she started complaining to the city of Oakland.

“I feel like I’m being forced to relocate,” she says. “I don’t feel like it’s a safe environment to have children around. And we do our best, and when you come in here, it’s like you’re in Disneyland. But the minute you walk back outside, you’re faced with everything that’s out there.”

Oakland Councilmember Noel Gallo represents this area.

“My biggest concern is that, you know, Home Depot,” he says. “And they’re losing a lot of their carts, their plant material, their lumber. And they’ve already threatened to leave that site cause they’ve lost 25, 27 percent of their business as of recent.”

A Home Depot representative from corporate headquarters denied that the store was considering relocating.

It’s not clear that the residents of the Community of Grace have anything to do with those thefts or the other complaints. Though they’re not on Home Depot property, their proximity makes them an easy target. A lot of people come here who don’t live here. People who don’t live here, for instance, dump trash in the middle of the night. But the Community of Grace still gets the blame.

But the community has a secret weapon. Someone with big ideas. Her name is Markaya.

“To be honest with you, I am a shocker for the city,” she says. “I am a shocker to a lot of people.”

Markaya is deeply passionate when she speaks.

“Even I get, hm, I didn’t know you, you don’t look homeless. What does homeless look like? I’m confused,” she says. “I’m not homeless. I have a home. It’s just not hooked up to their resources.”

Markaya has a different way of describing where she lives.

“What I call us is a self-contained off-grid community within Oakland’s community.”

She’s on a campaign to change the way outsiders see the community and people like her.

“One thing is the businesses need to stop always trying to blame us for everything. We’re not the ones doing it,” she says. “So don’t blame it on us… The main place I’m talking about is this gymnastic studio over here.”

Markaya is a single parent, and she says it’s important for children who live in the community to have a safe space too. She told me there can be up to a dozen children living here at any given time. In fact, she designated the 100-ft area around her living space a kid-friendly zone.

Markaya and her daughter and dogs live in a tiny house that they built with help from friends. It has a wood-frame arched roof that she designed herself. She gets her electricity from a generator. She gives me a quick tour.

“I got my little windows, the TV shelf built on the wall. I got a couple of little figurines and dolls, antiques… My little power station is hooked up for my phones and stuff. I got my light over there.”

Her daughter Za, eight, has her own room.

“I like to live here because I have puppies, my mom, my friend Jody and all my toys,” says Za.

This family has three generations living here. Markaya’s aunt, Claudette Smith, is in the RV next door. I ask Claudette how long she’s been staying here.

“I was in a really bad car accident this summer, so when I got out the hospital in September,” she says. “It’s just because I became disabled, and you can’t pay no rent on disability. Do you know how much we get? It’s only 900 dollars a month.”

She says Markaya got her a camper and moved her in after she got out of the hospital.

“My grandmother is her mother,” says Markaya. “I was raised by my grandmother. So we’ve always lived together.”

“They check on me at night,” says Claudette. “She make sure that door is closed and locked. And everybody know don’t mess with Auntie.”

“They check on me at night. She make sure that door is closed and locked. And everybody know don’t mess with Auntie.” – Claudette Smith, resident

Markaya’s been here less than a year, but she’s already become a leader. She got the city to start trash pickup. She joined the nine-person committee that oversees the community. I ask her how she stepped into that role.

“I just did. I have a kid. So my thing is in order for me and my kid to be okay, it has to be a structure. It has to be.”

Maria’s on the committee too.

“[Markaya] has a lot more, I don’t want to say respect, but a lot more persuasion with people,” she says. “Like I’m a little soft, and when things need to be asserted, she’s more assertive like that. So she actually held down the fort like a lot of times where I’ve kind of been a mess.”

Most importantly, Markaya and Maria have helped set up rules for the community, sixteen in total. Maria lists them out for me. They’re rules cover things like no stolen property or violence and the equal distribution of all donations. One rule in particular is a big source of conflict.

“Number 12, no garbage in areas,” says Maria.

“Number 12, no garbage in areas.” – Maria Fuentes, resident

Trash makes neighbors complain to the city. Markaya has a problem with one particular spot.

“All this garbage and just unnecessary-ness,” she says, exasperated. “It’s just nasty.”

We’re in the back of the city lot. A dirt path takes you past tarped-up structures, cars and RVs. Some days I pass a man tinkering on a motorcycle. Near the back are two tiny houses. The framed pictures hanging from one read “Adventure Awaits” and “Relax.”

“For the last I would say three and a half maybe four months, they have been told to downsize and reduce their footprints which means get rid of a lot of the stuff that you have,” says Markaya. “They’re eyesore.”

The next day, Maria pays someone in that area a visit.

“Okay, so they have made an attempt to clean this a little,” says Maria. “I don’t know if she has personal issues with these guys or what. But if I see some kind of progress, I cannot just ask them to leave or evict anybody. You know what I mean? That’s the last, last thing we want for anyone.”

Maria walks up to an RV. There are stacks of tires and blue plastic barrels right next to it.

“Knock knock. Knock knock,” she calls out. “You up? You up Teresa? It’s Maria.”

Teresa answers the door. She lives here with her husband and dog.

“I see that you guys are making progress,” says Maria. “You guys are cleaning up and I see that.”

I later ask Teresa what she thinks about the situation.

“They told us that because my husband, he’s a little bit of a messy kind of, you know, he leaves stuff places,” says Teresa. “He works on things and has ten different projects at one time and so forth. And so I’m running constantly behind him cleaning up behind him. But they have made threats that he had, they have to move. And if he has to move, I have to move.”

In a way, Teresa’s situation in the camp is like the camp’s situation in the neighborhood. Her future depends on her ability to control a mess. Some of that mess is not hers. And there’s not much in the way of services to help out.

That’s something Markaya’s been trying to change. At first, the community had one city-provided porta-potty. This was not enough.

“When I got here, the porta potty actually was filled with everything under the sun: body waste, clothing, needles, cans, bottles,” says Markaya. “Whatever you could think of was pretty much in that porta-potty. They wouldn’t service it. So literally me, Maria, you know and a couple of more people had to literally go in there and pick everything out with a picker.”

Markaya eventually secured six toilets, but they’re now back down to two. When I peeked in one, it was spotless. It even had a bath rug. Markaya also got the city to start trash collection, so residents don’t have to do their own hauling. She’s gotten so good at dealing with the city, she’s got a semi-official position. Lara Tannenbaum, with Oakland’s Human Services Department, explained it to me.

“Some of the sites where we have the porta-potties and the garbage pickup, we have what we call site leadership where there’s an identified person that helps keep the porta-potties clean,” she says. “We provide cleaning supplies and a small stipend to do that work. There is investment from people in that site. Amongst at least some segment of the folks there, they want the trucks to be able to come in. They want the porta-potties clean. They want their garbage picked up.”

But the city doesn’t officially sanction the community, or any encampment. And the city won’t necessarily let it stay.

Joe DeVries, assistant city administrator, works on the city’s response to homelessness.

“We know that there’s been a lot of problems there,” he says. “There have been threats of violence against some of our workers. There’s, there’s a certain element at that location that has caused severe problems for the neighboring businesses. … So it’s unfortunate because we’re dealing with a mixed bag.”

What’s striking is how much work it takes to keep this community going. Getting the tiny houses built requires carpentry skills. Handling the mess takes organizing. Getting trash pickup and sanitation requires navigating city bureaucracies.

And then there’s the problem of how you get clean water to a community of approximately 50 people, with no plumbing.

“It’s simple,” says Maria. She explains that residents go to a nearby fire hydrant.

“You get a wrench, a big enough wrench to just turn the knob. And the water will begin to sprout out and there we try to funnel the water to go into our water containers or our jugs by putting half of a two-liter, you know, just cut it open and put it over the thing because it sprouts out like that.”

Technically, tampering with a fire hydrant is a crime. But residents of the Community of Grace have to risk arrest just to get water.

Making the community work also requires enforcement.

“We have male security, we also have female security,” says Markaya. “I’m part of the security as well.”

The community’s security team is there to protect the residents’ safety.

“I want everyone to feel safe,” says Maria. “This is the whole point; it’s a safe zone. If there’s people that are feeling they’re being intimidated, bullied, sexually harassed or anything, we won’t tolerate that. I will not tolerate that.”

“If there’s people that are feeling they’re being intimidated, bullied, sexually harassed or anything, we won’t tolerate that. I will not tolerate that.” – Maria Fuentes, resident

But sometimes people come who cause trouble.

“Somebody gets to the point where okay, this person is bringing in stolen cars for example to the community over and over again,” explains Maria.

Stolen cars draw police. Police attention could get the whole community shut down. So to keep the community from getting thrown out of the neighborhood, the community throws people out of itself.

“We’re trying to avoid calling the authorities at all costs,” says Maria. “That’s the worst case scenario. But if any harm comes to the community, we do count on our own enforcements. And that’s when we get a little ghetto and a little street.” She laughs.

They also have to watch out for newcomers. Assess them. Explain the rules. First thing most days Maria and Markaya make security rounds. I join Maria one morning.

“I’m not even really dressed for this, like it’s way too early,” she chuckles.

To get to the back of the community, Maria walks past a concrete barrier spray-painted “No Dumping.” On one side of the street sits an RV with a garden. There are potted plants, a sculpture of a goose, a carefully arranged ring of rocks. On the other side, an empty lot with a big orange “For Lease” sign.

Maria stops to chat with Robert, a new arrival whose mom lives here. They have a brief check-in because the community has a protocol for new people who want to move in. For one, new residents have to have their own space and something to live in, typically a tiny house or RV. Maria asks him if he has his own space.

“No, I don’t have my own place. We weren’t told that we were approved for one,” he says. “I don’t necessarily know how long I will be out here. But I’m gonna try and be out here as long as I can.”

“But yeah, you’ve been approved if me and Markaya are communicating with you and you know,” she says. “You need your own space.”

“Y’all were needing an interior security officer?” asks Robert. “And I have my certification. Not here, but I have it from Oklahoma. I got the cuffs, I’ve got the training and everything else. So she said she’s going to talk to y’all and probably make that happen.”

“Yeah, we’d be willing to chip in and pay for something like that,” says Maria.

“Oh, I weren’t expecting no payment,” he replies. “I live here. It’s community.”

Lately, there have been a lot of newcomers. And that’s been tough for the community to manage.

“The city kept sending people over here,” says Markaya. “It started, I want to say August is when they started telling people to come over here. When 23rd and East 12 caught that big fire, that’s pretty much when they started, the police started telling people, oh go over there by Home Depot. Go over there by Home Depot.”

I ask her how she knows it’s the police that was telling people to come here.

“They told us,” she says. The people that are getting turned away tells us.”

This is a common complaint across Oakland: that when city workers or police officers evict one community, they direct people to other ones. According to Oakland’s Joe DeVries, this is not official city policy, but city workers may do this and help people move in some cases. Some advocates though say the problem is more widespread than that. I asked a former resident from the place Markaya mentions, at East 12th and 23rd, if the city helped move in new people into that site.

“They definitely brought them,” says one former resident from that site. He says he saw the whole thing. “During the course of two maybe three days, they brought about twenty people.”

He says he was there when city-owned flatbed trucks moved in people’s belongings.

“It was the city dump trucks,” he says. “Not sanitation, but dump trucks.”

A sudden rush of new people who are unused to the rules can create problems that give the city a reason to evict everyone. A few weeks later, that’s what starts to happen here at the Community of Grace.

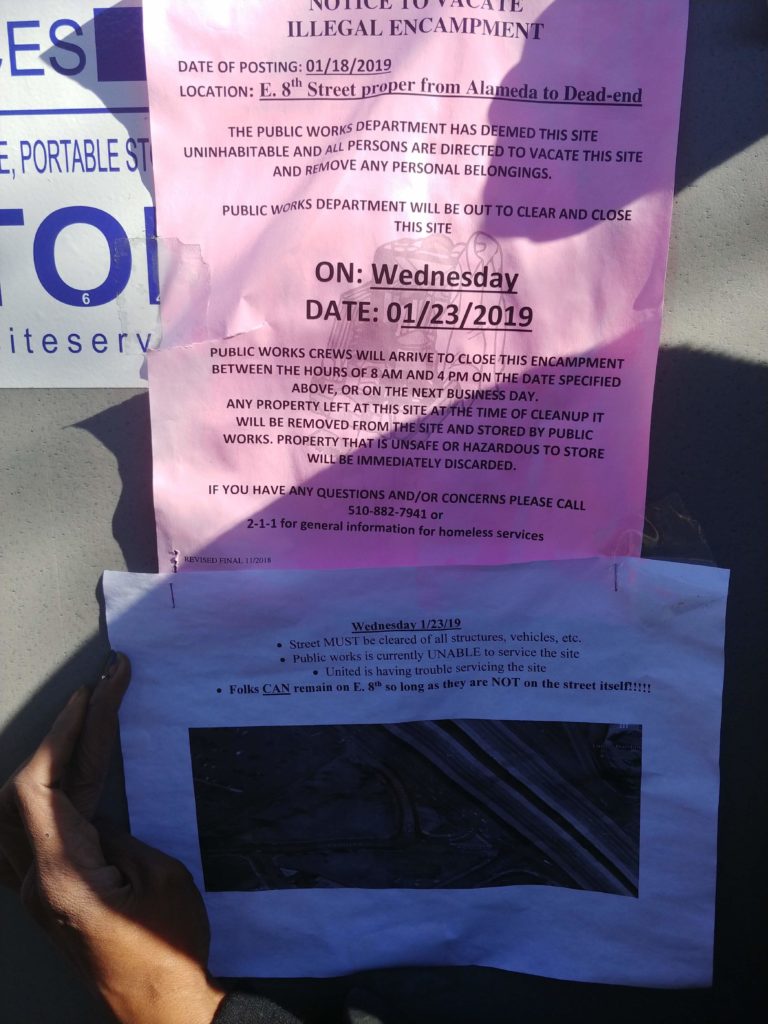

“New people or the people that are there have really just completely dysregulated themselves,” says Oakland’s Joe DeVries. ““They’re parked in such a way and they have structures that are built in such a way that we can’t even get a garbage truck in to do the servicing. And so we had to post it for a partial closure. We need them to clear the street.”

The city has posted notices that East 8th Street will be closed permanently. Anything that’s not on the sidewalk will be removed. Markaya’s tiny house is on this street where evictions are happening.

“A lot of people are being reshuffled. If we don’t reshuffle, they’re going to get kicked out,” says Markaya. “Because if you don’t move your trailer, they’re gonna tow it. If you have a house structure that’s on the street, they’re going to tear it down.”

“If you don’t move your trailer, they’re gonna tow it. If you have a house structure that’s on the street, they’re going to tear it down.” – Markaya, resident

I ask her if she’s surprised by this.

“No, I’m not,” she answers. “But it’s just, it just shows what we go through.”

Markaya’s house is mostly on the sidewalk. But there is one room that juts out into the street, which means that one room needs to be cut off.

When I arrive the day of the eviction, Oakland workers are trying to figure out how to take her house apart and then reconfigure it so it fits on the sidewalk. Markaya watches nearby.

“I need a cigarette,” she mutters.

But later, she tells me, “I’m not really trippin’ off of it. It needed to be done.”

Three weeks later, Markaya is still making repairs to her house with the help from the multi-tool blades she got online for her first time. Her house leaks now sometimes. And her television and phone got broken during the move.

“I haven’t been able to seal up all the walls,” she says. “It’s been a process. It’s been hectic.”

Even as Markaya’s patching up her home, there is a more permanent eviction looming.

“What you see today is something that we need to address cause we do have money to redo 42nd Avenue, connecting it from 880 all the way across to Alameda Way,” says Councilmember Noel Gallo. “East 8th will remain where it is. But it you know, 42nd runs right above it, right behind our, the parking lot of Home Depot. It runs all the way across where you see all the campers, that’s a street and that’s a city street… We need to we need to relocate the homelessness so we can connect the street.”

The city has secured millions of dollars for this project. The goal is to improve traffic flow and economic development. He says there are plans to create a city-sanctioned RV parking lot for residents to move into. But of course, not everyone has an RV.

I ask the councilmember when he thinks the Community of Grace might be relocated. There’s no firm timeline yet, but he replies, “If we could do it tomorrow, I would do it tomorrow.”

“If we could do it tomorrow, I would do it tomorrow.” – Oakland Councilmember Noel Gallo

Taking care of basic needs, staying on the right side of the city and the neighbors, running security, moving her house: this is all work, hard work – especially when you’re doing it all in one of the rainiest winters in California history, when you have to hop over giant mud puddles just to get around. A few months after I first meet her, Markaya is done.

“I’m thinking about moving,” she admits. “Hopefully soon, if I find a location that I like. I want to move because it’s starting to become out of control over here. When you have people that comes from different encampments, they come with their mindset that they came with, as well as people that was already here starting to pick up their ways as well. So it’s just becoming too much.”

I ask Markaya if she’s burnt out.

“Very burnt out. Exhausted,” she replies. “Being a site lead here, it makes it just even more difficult because every ten minutes somebody is running to me with some kind of issue. So I’m having to deal with that and not be able to handle my own business.”

Markaya is looking for a new place to move, somewhere empty and somewhere she can bring her family and start a new community. She’s told me several times she wants to create a national model. She’s looking forward to it.

“Oh, I’m ecstatic when I can move. I would be so happy. It’ll be a change. I can’t wait.”

Markaya is also working with an advocacy group, the East Oakland Collective, to shift the narratives around homelessness. Perhaps a new model community could be part of that work.

“My passion and my dream is to make sure you know grandkids, great grandkids and further on down the line don’t have to struggle and go through this, that things are in place that are ready for them.”

I drop by to see how Maria’s holding up. It’s Valentine’s Day. She’s dressed up: she’s got on lipstick, a red dress, and heels. But her face is troubled.

“I’m just tired,” she says. “I’m tired being out here five years, you know even saying it to you over, you know, the microphone the other day, the last time we had the interview was like wow, I hadn’t realized, damn, I’ve been out here for five years… People come in knocking on my door, every two seconds is frustrating and overwhelming sometimes.”

And when Maria gets overwhelmed, she can go to a dark place.

“I use methamphetamine,” she tells me. “Yes, crystal. Not as much as a lot of people, but it’s enough for me… My addiction is real, real fierce, and I need to get a hold of it. I need to get control of it.”

She laughs. “It seems like I have it all together sometimes, and then the next minute you realize you don’t have anything together.”

Maria says she’s been using crystal meth, on and off, for the last two years. And it’s keeping her from the things she loves the most – or rather, the people.

“José Luis, Irene and Angelina,” she names. “And they’re my three beautiful, everything-in-this-world babies.”

Her two youngest are five and eleven. They live with their father’s parents. Her oldest daughter is thirteen. She’s with Maria’s parents in Palm Springs.

“The father of my children is out here, Jose. He lives right across the street. So we’re both homeless, and we can’t have them out here homeless with us.”

Maria thought it was better to have her kids stay with their grandparents. In fact, her kids don’t know that she’s living on the streets. She thinks it was the right thing to do.

“It kills me, kills me every day,” she says. “I really want to be a part of their lives, you know.”

“It kills me, kills me every day. I really want to be a part of their lives.” – Maria Fuentes, resident

Maria says her oldest daughter knows she uses methamphetamine. “There was a point in time where I had to block her on Facebook because she was saying some really really horrific things that were true, that were true… She has her feelings. She feels like I’ve chosen this lifestyle over her.”

But Maria says she wants her daughter to know one thing.

“That I love her. And that the only reason why I’m not with them is because I didn’t want them out here with me like this, to live in these conditions… I want her to know that I didn’t do it because I didn’t love her, or I didn’t care about them. Because I so think about my kids every day, every day. Every day, every hour, I’m thinking about my babies.”

But Maria can’t tell them that because she doesn’t want to see her kids while she’s still using. She says she wants to go to Cherry Hill, the only sobering station and detox center in the county, to get clean for three days.

Dr. Aislinn Bird, a psychiatrist with Alameda County’s Health Care for the Homeless, said at that point, Maria may still be in withdrawal. The county does have residential programs that will take people coming out of detox. But those beds are often full.

“I just want to be sober enough to go go see the kids,” says Maria. “And then I’m not planning on going back to using after I see them. I’m hoping that they can put me on a program or maybe get me involved in some outpatient.”

There are some obstacles to that plan. Maria doesn’t have a phone. She doesn’t have a car. And that makes it hard to get to appointments.

I checked multiple times with Maria if she wanted me to share her story about addiction. She always said yes.

“I would like that to be heard because it’s real. And addiction is real. And losing your kids really happens. And I know there’s a lot of moms out there like me. And I know they love their kids.”

Maria hasn’t gone to visit her kids, not yet. When she does, she wants to go prepared – and sober. In the meantime, she has her community.

“I feel like the richest girl in the world because of the love and the friendship and the people that I have around me. But homelessness is still happening. And I’m still homeless. But I couldn’t ask for it any other way right now. Like … I feel like Oakland in general is a great place to call home, and that keeps me going.”

“Oakland in general is a great place to call home, and that keeps me going.” – Maria Fuentes, resident

Lucy Kang is KPFA’s features reporter. All photos by her.

Producer’s note: The city avoids using the word “eviction,” arguing that it implies a legal right to the land. The United Nations however, does use the word eviction in reference to homeless encampments. I’m choosing to use it here because the words the city prefers, “closure” or “clearance,” erase the humans beings who are displaced.

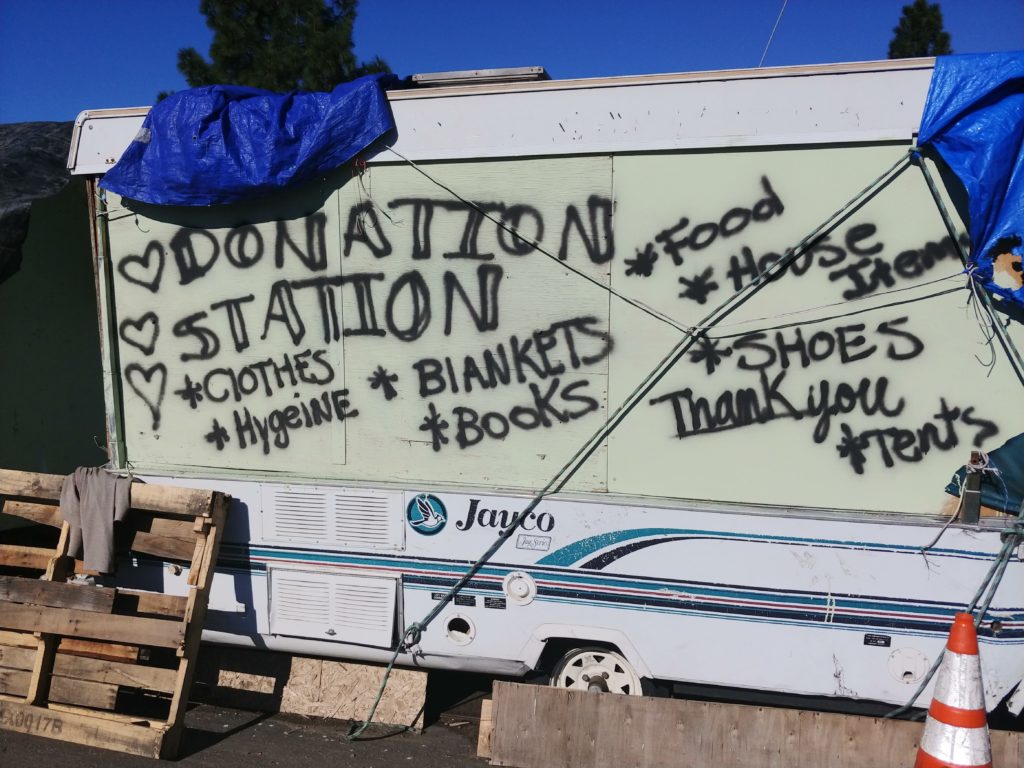

The Community of Grace is accepting donations for drop-off.

For more information about Alameda County’s addiction support services, please call the Acute Crisis Care and Evaluation for System-Wide Services (ACCESS) line at 1-800-491-9099 or go to http://www.acbhcs.org.

(5/6/19 Update – The text version of this story was revised to include Home Depot’s response that they are not, in fact, considering a relocation. Other parts were edited for greater accuracy and clarity.)